July 28th marks the 88th anniversary of the clash that ended the U.S. veteran’s protest movement known as the Bonus Army, or Bonus March. Today, we’ll use this social studies topic to explore hypertexts and hyperdocs to create learning.

Editor’s note: Random-Access Memories is a periodic series highlighting the ways in which major historical events have influenced and can be explored through ed tech. Got an idea for a future edition of R-AM? Drop us a line.

It was a summer of continuous protests, and the demonstrators were met violently by state forces deploying tear gas and military units to break up the demonstrations. It was 1932, and veterans from across the nation gathered in Washington, D.C. to demand economic relief. Today it’s know as the Bonus March and its participants called the Bonus Army, and it’s an important chapter in the history of the Great Depression and the World Wars and economic transformations that bookended it.

As a historical subject, the Bonus March as an opportunity to explore history through hypertext, especially hypertext that includes primary-source documents.

Linked Learning

We mostly encounter hypertext in our everyday life as links or hyperlinks. You know, like this. E-readers also display a kind of hypertext, allowing you to skip to a chapter or bookmark in the digital text. Google Docs and other apps, like Slides? Those include hypertext features, too — sometimes called hypermedia to include videos, audio, and other multimedia — just like links on a web page.

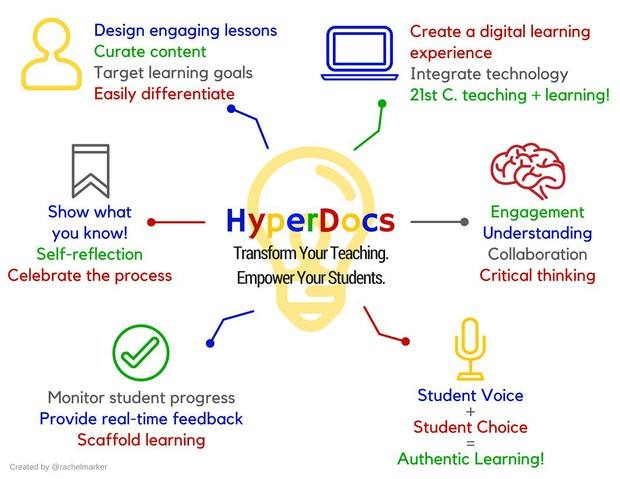

Since its inception, hypertext has been seen by educators as a potential way to increase engagement with text and media and encourage self-directed and deep learning. Hyperdocs, a kind of hypertext document used in education to collect multiple parts of a learning cycle, can be a great way to deploy hypertext to encourage student voice, student choice, collaborative learning, and more. In this post, we’ll look at one small example: How we might use hyperdocs to teach a social studies lesson about the Bonus March of 1932. Have your own ideas for using hypertext to teach? Let us know in the comments!

The History of Hypertext

It got its start, unsurprisingly, in education. Researchers at Brown University first developed a hypertext system in the late 1960s. The intention was to link different texts in a computer system, allowing users to move from idea to idea, building a large, self-guided context for learning. The result, the “File Retrieval and Editing SyStem” (FRESS) was initially a huge development in computer science, but it quickly caught on in education.

One of the best examples came in 1976, when FRESS proved itself to be as revolutionary for education as it had been for computer science. Collaborating under a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant (“An Experiment in Computer Based Education Using Hypertext”), Andy and Professor Robert Scholes of Brown’s Department of English used the system to create a poetry textbook and linked corpus for students and instructors that contained course texts, supplementary materials, and an ongoing omnidirectional commentary and threaded discussion that they created themselves.

“A Half-Century Of Hypertext” Brown University Computer Science

Eventually, of course, hypertext became one of the building blocks of the world wide web and the internet as we know it. And with the omnipresence of the internet today, it’s easier than ever for educators to deploy hypertext and hyperdocs in their teaching.

Effectiveness of Hypertext

Hypertext tools can be effectively used in education, and combined with other proven techniques. Technology Integrationist Michelle Wendt notes that hyperdocs in particular can “engage learners using the four C’s—collaboration, communication, critical thinking and creativity.”

An academic study by Conradty and Bogner in 2016 finds that hypertexts, compared with textbooks, can provide individualized learning and “may support individual motivation and activate thinking abilities, intensify elaboration, permit creativity and cultivate learning by discovery.”

Any hypertext offering the option to deal in more detail with the subject requires additional involvement with it, so that the outcome is less likely to be just linear learning but a networked thinking process. Students have to process the learning matter, resulting in meaningful knowledge unachievable by rote-learning alone.

“Hypertext or Textbook: Effects on Motivation and Gain in Knowledge,” Cathérine Conradty and Franz X. Bogner. University of Bayreuth 2016

Using hypertext is also related to the concept of mind-mapping, and different ways of learning through note-taking. And don’t forget, you can deploy hyperdocs in the service of a number of other proven techniques like the Jigsaw method.

The Hype Around Hyperdocs

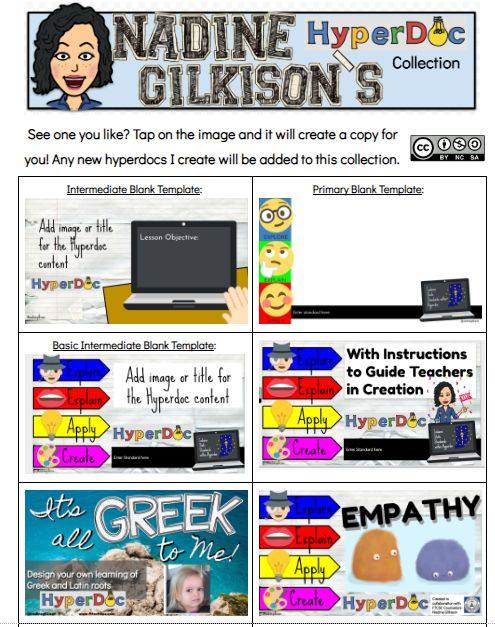

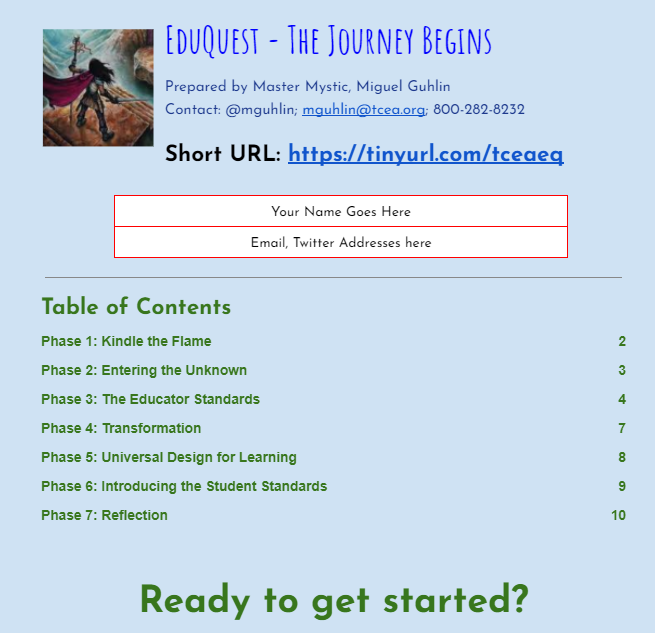

The term “hyperdocs,” a combination of hypertext and document, was recently coined by educators Lisa Highfill, Kelly Hilton, and Sarah Landis to describe hypertext documents that act as a digital “hub” for a unit or other learning cycle.

Now that Google tools like Docs and Slides have become so prevalent, teachers are using these tools to create similar lessons, choosing and mixing resources that go well beyond simple web pages. Last year, we looked at something called a playlist, which teacher Tracy Enos used to organize her language arts lessons and differentiate instruction for her students.

Jennifer Gonzalez, “How HyperDocs Can Transform Your Teaching” Cult of Pedagogy

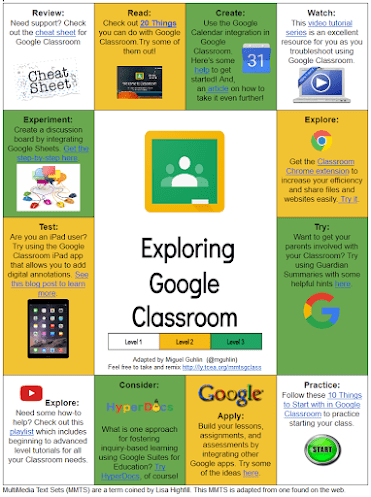

Moreover, hyperdocs can integrate with any number of effective teaching models like the 5E model and more. Don’t be afraid to deploy hyperdocs in professional learning as well. You can even use hypertext in slideshows (aka “hyperslides”) to create interactive games. Tools like Google Draw can be useful to create what Joli Boucher has dubbed “hyperdrawings.” In social studies, graphs, charts, maps, and more can easily be integrated into hyperdrawings.

One popular method is using Google Slides, which can embed a number of multimedia types within a shareable presentation. Check out the video from educator Sam Kary below to see how he uses hyperdocs through Slides, especially when engaging in remote learning and teaching.

A Hypertext Example: The Bonus Army

In 1924, Congress promised veterans of World War I, then called the Great War, a cash bonus for their service. This bonus originally could not be claimed until 1948. During the Great Depression, however, many veterans of the war were out of work and without a safety net. Many demanded their bonuses be paid out in order to alleviate the economic strain.

By mid-1932, tens of thousands of veterans and their families marched across the nation to Washington D.C., where they camped near the U.S. Capitol in protest, until they were violently expelled by the U.S. Army on July 28, 1932.

While the government did not immediately respond to the protests, President Herbet Hoover’s already struggling reputation took a hit, affecting the 1932 presidential election. The victor, Franklin Roosevelt, took a softer tone with continued protests, though he still vetoed an attempt to pay out the war bonuses early in 1936. Congress overrode the veto and the veterans received their bonuses just five years before the U.S. would enter a second global war.

For a history-focused hyperdoc example, check out the hyperdoc on this topic we’ve created, integrating the 5E model.

Existing Hypertext Resources on the Bonus Army

Looking for a place to start? Check out these digitally-enriched resources for learning about the Bonus March.

- The Soliders Bonus Act from the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center

- “Veterans March to Washington” Broadside, December 5, 1932 from the State Historical Society of Iowa

- “Occupying” the Bonus Army Protests of 1932 from the Library of Congress

More History Hypertext Resources

- Digital Resources for Independence Day

- StoryMap JS: Creating Immersive Social Studies Education

- Timelines Made Easy

Exploring Hyperdocs

- Empower Learners with the 5E Model and Hyperdocs

- Hyperdoc Happiness: Transform Teacher Inservice

- HyperNotes? Use Hyperdocs with MS Office 365

Photos via DC Public Library Commons and Wikimedia Commons