“I was using jigsaw with my students before,” said the science teacher at a private school. “Now that I know its effect size, I’m going to be using it even more.” The insight about the jigsaw strategy popped up after discussing John Hattie’s meta-analysis. If you’re not familiar with it, he analyzed a lot of research. His meta-analyses identified the effect size of instructional strategies used in schools today. Let’s take a moment to see how jigsaw works and in the context of educational technology.

The Jigsaw Method

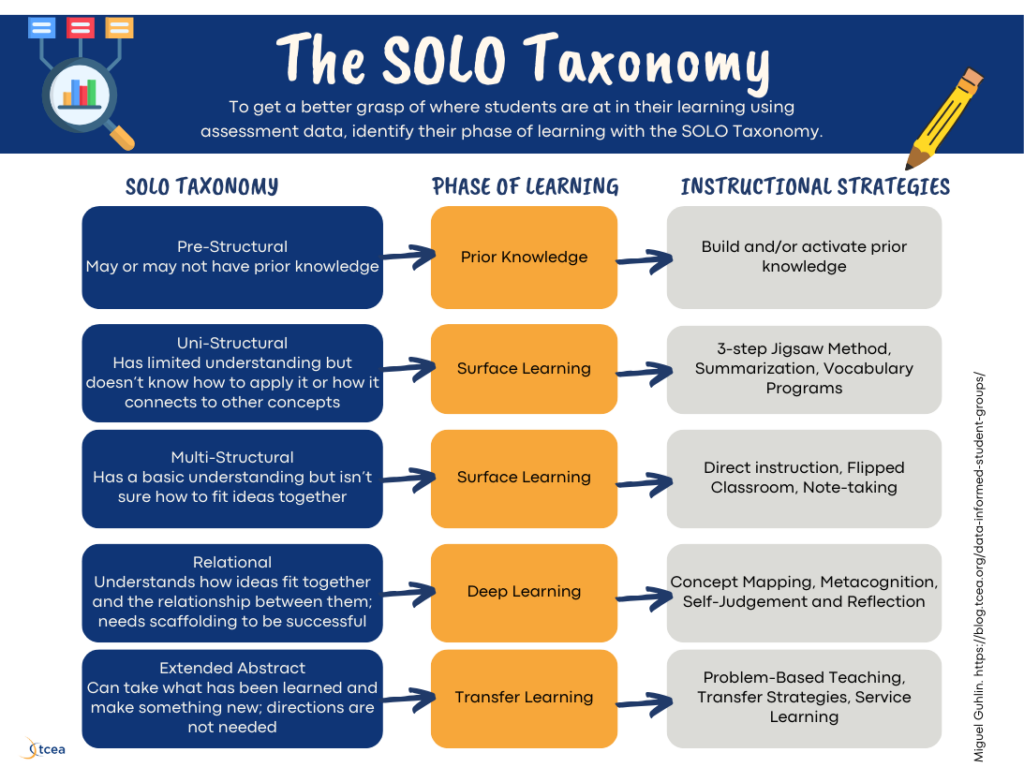

“The Jigsaw Method is a teaching strategy. It is useful for organizing student group work,” says Jordan Catapano. “It helps students collaborate and rely on one another.” John Hattie found the jigsaw method to have an effect size of 1.2. What does that mean? Consider that the average growth any student experiences over an academic year is .40. This means that using jigsaw in a consistent manner can accelerate student growth. Students in your classroom will see greater than one year’s growth with the jigsaw.

As I was working on my PBL with Minecraft: Education Edition session, I realized I had a lot of resources to share. I asked myself, “Would the jigsaw method work well enough to get the job done?” Before I share how that worked out, it might be worth reviewing how the jigsaw method works.

Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey suggest there are three types of jigsaw methods. After reviewing their list, I realize that they are right.

Approach #1: Jigsaw as Divide and Conquer (One-Step Jigsaw)

This was my first introduction to the term “jigsaw.” This ineffective application of the label serves as a way to divide a long article into pieces. Each group member takes a piece, then summarizes it for the small group (or large group).

Fisher and Frey share their opinion about this:

This “one-step” approach isn’t a jigsaw; it’s a divide-and-conquer approach to text. When teachers experience “jigsaw” in this way, they’re likely to replicate it incorrectly in their classrooms. Harm may be done as less effective readers share misinformation with the group and everyone’s understanding is compromised.

This approach may not be the best one to replicate.

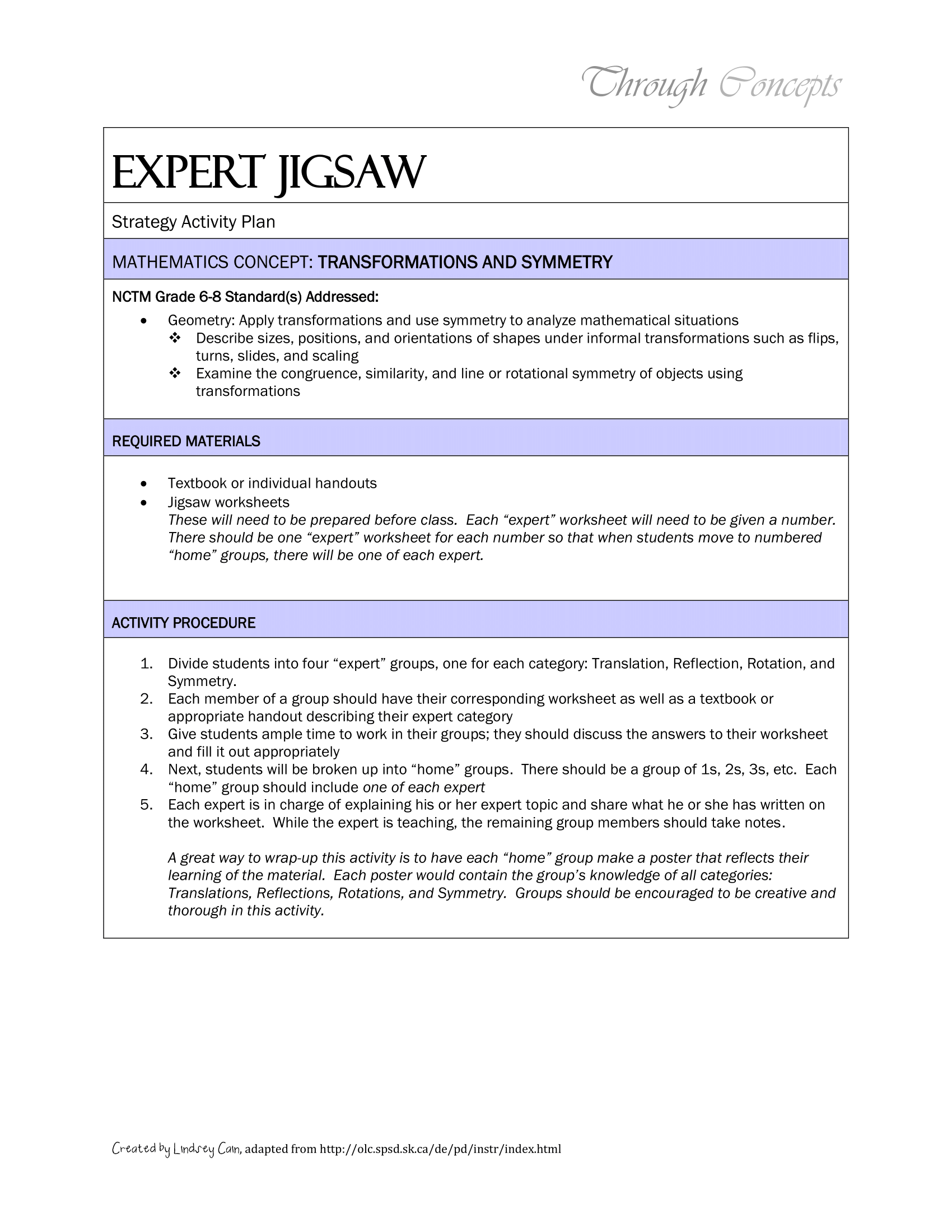

Approach #2: Home and Expert Groups (Two-Step Jigsaw)

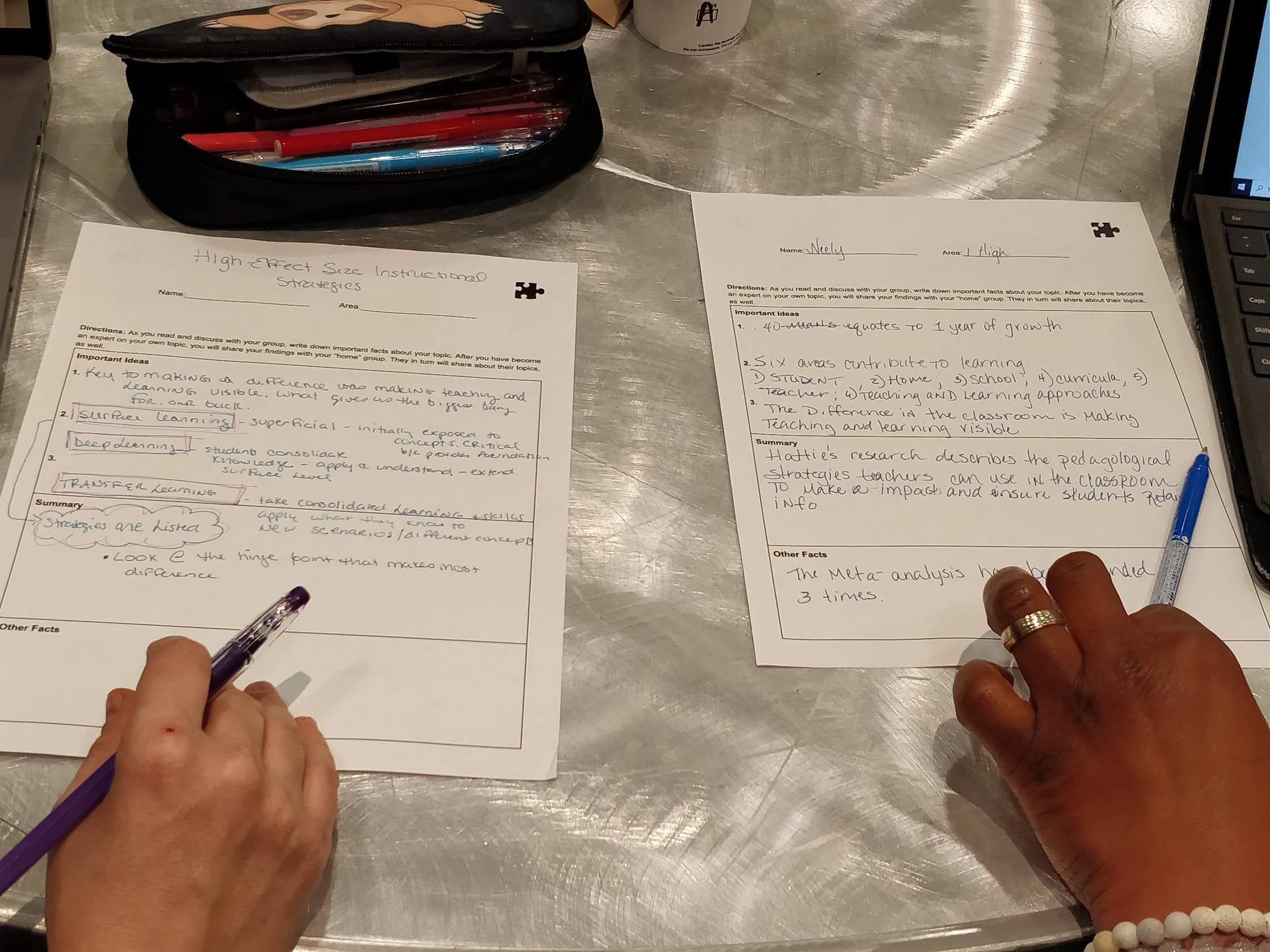

Only this summer did I attempt the home and expert groups approach to jigsaw. The process involved grouping students into “home” groups. Then, students chose one resource of the available list. Once students decided on their resource, they formed up into “expert” groups. The expert groups worked to plumb the depths of the same article. Then they discussed their takeaways with each other in their respective home groups. Here’s a link to the organizer my students used in Google Docs format.

This approach falls short as well, although not as much as the first approach. Frey and Fisher point out the following:

In this type of activity, learners still don’t have the opportunity to discuss how their assigned part fits within the whole text; groups just report on the particular section they read. And the critical thinking that’s accomplished through analysis and synthesis doesn’t happen.

How do you get students to do more than report on the particular section they have read? More important, how do you make analysis and synthesis to happen?

Approach #3: True Jigsaw (Three-Step Jigsaw)

The critical third step of the three-step jigsaw involves students returning to their expert groups. Once back in expert groups, they discuss how their part fits into the whole. Fisher and Frey describe it in this way:

In the third phase of the jigsaw, students return to their expert groups and discuss how their passage fits into the whole text, based on their discussions with their home group. The point of this third phase is to have students engage in a part-to-whole conversation in which they arrive at a deeper understanding about the text and its implications.

Students think about their thinking (metacognition) and synthesize and analyze ideas contained within the complete text. This process requires that students listen carefully to their peers and analyze the ways in which each part contributes to the entire text.

As you can see, step three of the this jigsaw approach involves heavy lifting. As such, I see the phases of movement as follows now:

- Divide students into home groups to split up portions of text or resources.

- Set up a way for students to group according to expert groups to explore their specific area.

- Regroup into home groups to discuss findings.

- Split into expert groups to consider the whole in light of specific area.

This constant movement of students from one group to another can be awkward. But let’s not forget how important movement is to the human brain and learning efforts. Without this heavy lifting, the jigsaw method in use may not be as effective. As you reflect on how you are using jigsaw in your classroom, which approach have you taken?

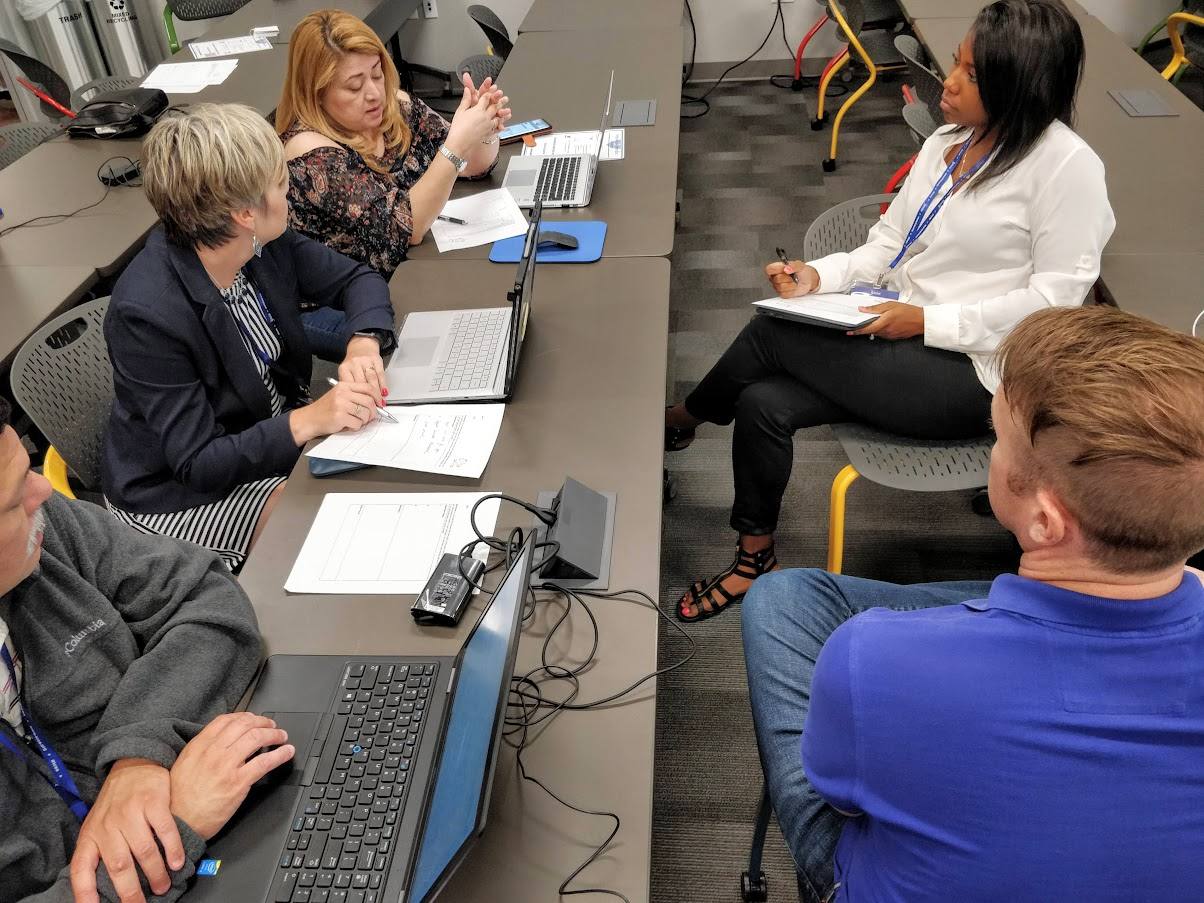

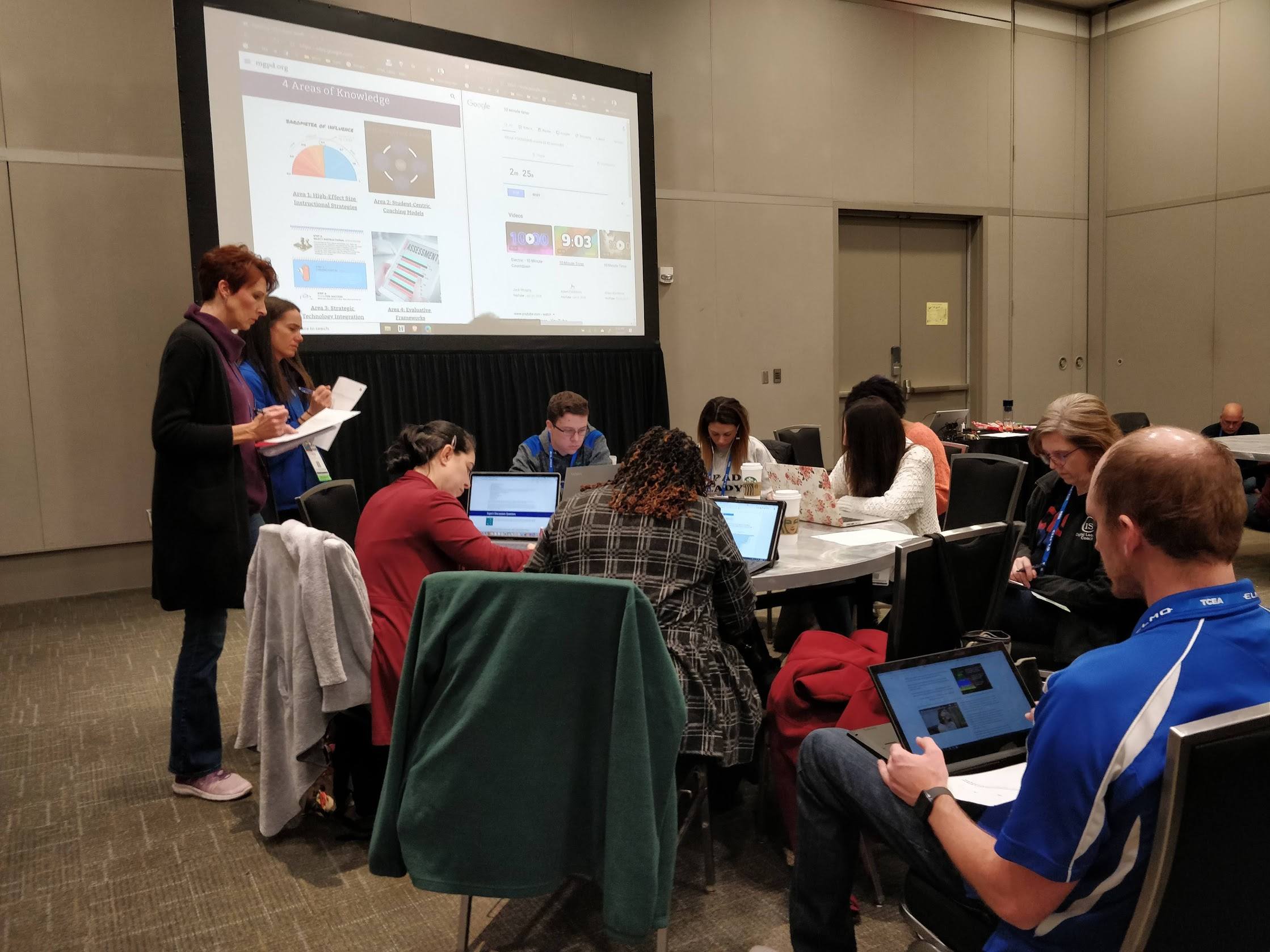

Reflections: The Jigsaw Method in My Workshop

In my face-to-face workshop, I relied on the two-step jigsaw. Rather than use a single resource split up into passages, I shared resources relevant to a theme. The theme? PBL in the Minecraft: Education Edition classroom. As I implemented it, students did not achieve the critical third level, but the activity did achieve my intended goal. Some of the participants were quite forceful in sharing their perspectives. You can see how this activity appears in my session materials. Visit Activity #1 – Exploring Possibilities to see it in action.

Some revisions I would make now that I know about the three-step jigsaw include:

- Include a quiz or performance task at the end of the two-step version of the jigsaw. This would fall into step right after phase three movement.

- Use some kind of metacognitive aid or scaffold (concept map?) to capture student discussion in the phase four movement. That’s the third step of the three-step jigsaw. In this phase, students move back into expert groups to discuss their learning in context of the whole.

What are your thoughts on the jigsaw approach and its use for professional learning or in your classroom?

Sign up for one of our Google Certified Educator certifications. You’ll learn about more than Google Meet, as well as earn 12 CPE hours per course. Use these courses to get Google Educator certified.

Sign up for one of our Google Certified Educator certifications. You’ll learn about more than Google Meet, as well as earn 12 CPE hours per course. Use these courses to get Google Educator certified.  Creating bite-sized chunks can be a lifesaver for learners. It makes the learning manageable, memorable, and improves comprehension (

Creating bite-sized chunks can be a lifesaver for learners. It makes the learning manageable, memorable, and improves comprehension (

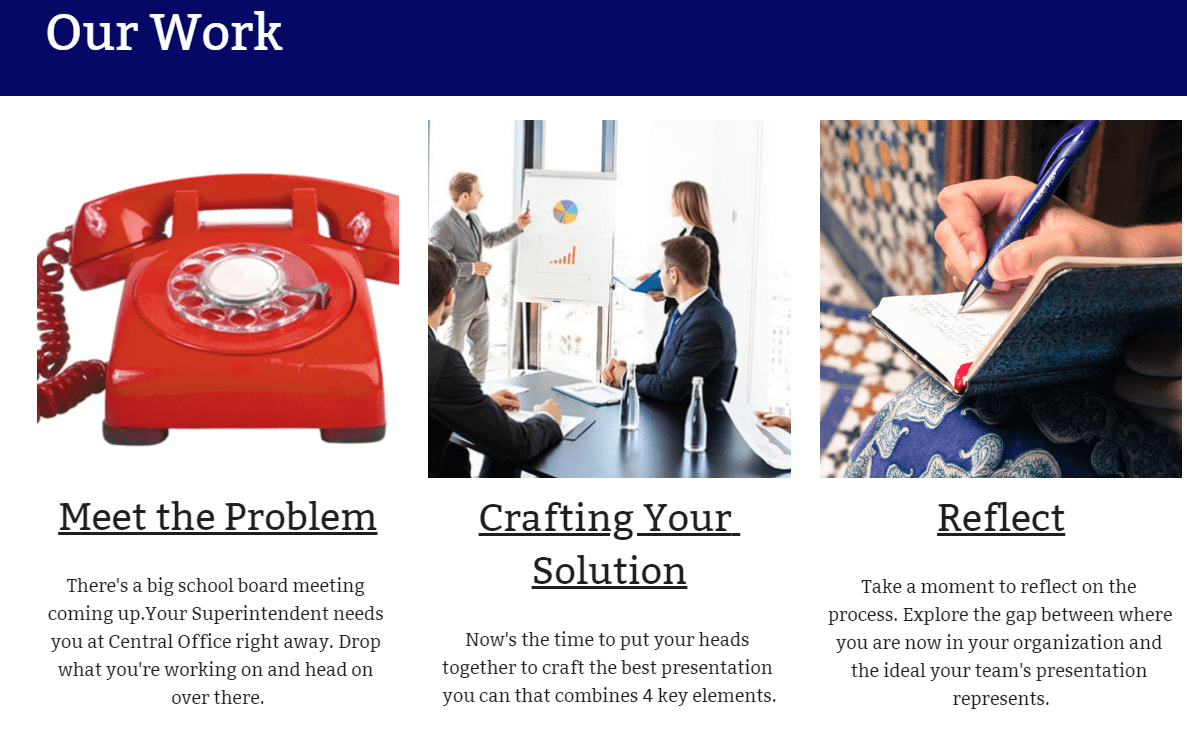

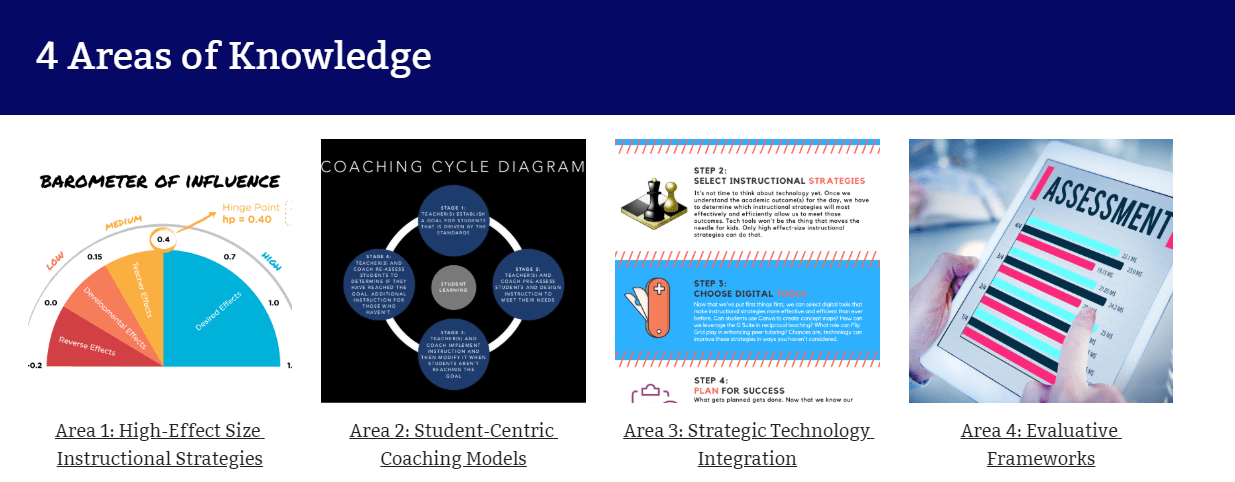

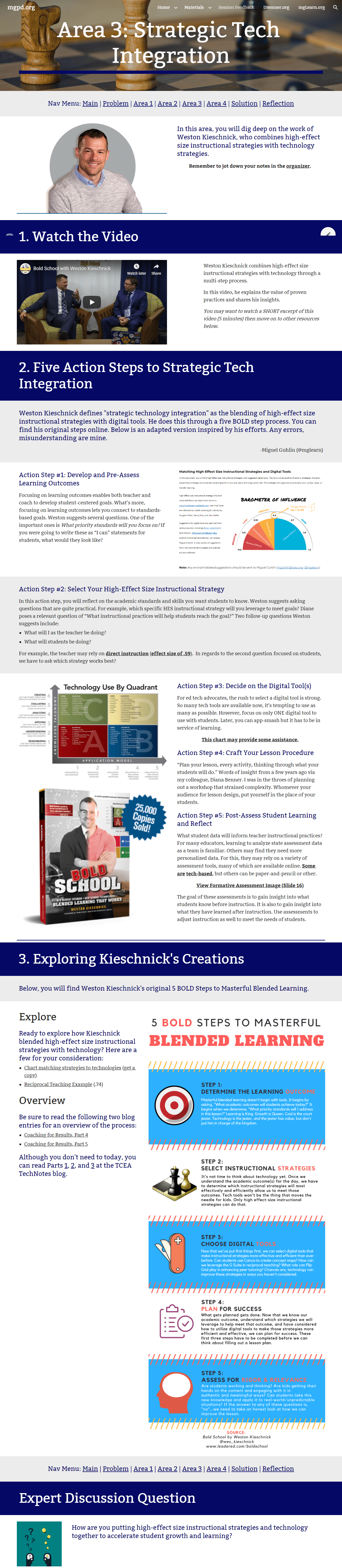

The project stations focused on four key areas. Those areas included:

The project stations focused on four key areas. Those areas included:

The jigsaw method is a cooperative learning technique that has been around a long time in schools. It’s powerful because it makes students dependent on each other (and not the teacher) to succeed. Students are divided into small groups of five or six each. One student assumes the role of the leader, either assigned by the teacher, as a volunteer, or chosen by the group members. The teacher divides the day’s learning into five or six pieces and gives only that piece to one person in each group. Students study their piece for a few minutes and then get into “expert” groups with others who also have the same piece of information. In the expert group, the students discuss the most important aspects of their piece and how they might best teach it to their peers. Then the “experts” disband and go back to their original groups where they share their learning. You can learn more about the

The jigsaw method is a cooperative learning technique that has been around a long time in schools. It’s powerful because it makes students dependent on each other (and not the teacher) to succeed. Students are divided into small groups of five or six each. One student assumes the role of the leader, either assigned by the teacher, as a volunteer, or chosen by the group members. The teacher divides the day’s learning into five or six pieces and gives only that piece to one person in each group. Students study their piece for a few minutes and then get into “expert” groups with others who also have the same piece of information. In the expert group, the students discuss the most important aspects of their piece and how they might best teach it to their peers. Then the “experts” disband and go back to their original groups where they share their learning. You can learn more about the