What if, in six sentences, you could empower students to create amazing work? It’s a preoccupation many science teachers have. Let’s take a moment and spend some time on CER: claim, evidence, and reasoning. Think of CER as a tool for student empowerment. You’ll see some specific examples with the help of AI tools such as Claude, ChatGPT, and an AI Lesson Plan Generator.

Many science teachers use the Claim Evidence Reasoning (CER) approach as a cross curriculum approach. It helps help students organize their thoughts to create better scientific explanations. This aids in constructing arguments and communicating their conclusions. This can be an effective approach which your students can then take to the workplace. (Adapted from source)

Some teachers suggest that schools use CER across the middle school curriculum. In that way, CER is relied upon as a way to teach argumentation. “If you are making a weighted statement, you’ve got to be able to back it up,” says Rachel Jennings Langley. That makes sense, but what IS CER anyways?

What Is CER?

In a popular science teacher Facebook group, a first-year science teacher asked, “What are CERs? What do you do with them?” She went on to ask, “Is this something I can incorporate with my curriculum for grades 6-7?” After reading the responses, I thought it might be a time-saver to organize them in this blog entry.

“Use the Scientific Method to do the lab. For the write-up, use CER. They compliment each other. CER is a great way to summarize the scientific method.”

Julia Calderon (edited for readability)

Some describe CER as an inquiry-based approach. “[CER] challenges students to explain what they found after completing a lab or observing phenomena,” says Gabriel Higdon. People often equate CER with the Scientific Method, and it’s not, says Higdon. Teachers who have access to curricula like STEMscopes have CER built-in. Some suggest that the Scientific Method should be “ditched.”

A Shout Out

I hope you don’t mind doing a quick shout-out to a science guru, Lisa Soll, at the Education Service Center, Region 20 in San Antonio, Texas. I really appreciate her science efforts and encourage you to drop by and visit her to learn more about science in education.

-Miguel

Ditching the Scientific Method

Erin Sadler (Sadler Science) argues that the scientific method gives the impression that science is linear, leaving out modeling and argumentation. What’s more, students seldom get enough practice on individual components and fail to connect science and engineering (source). Erin Sadler makes some excellent points, culminating in her piece on How to Use the Science and Engineering Practices. For many educators, CER serves as a way to get students to write about certain aspects of the science work they are engaged in. It certainly seems that there are different tools to use in the classroom. In Texas classrooms, CER is quite important.

AI Insight

Did you know you could use the free AI Lesson Plan Generator to create a CER lesson plan? Use this AI tool to create a CER intro activity. View one example.

What Does AI Say About CER?

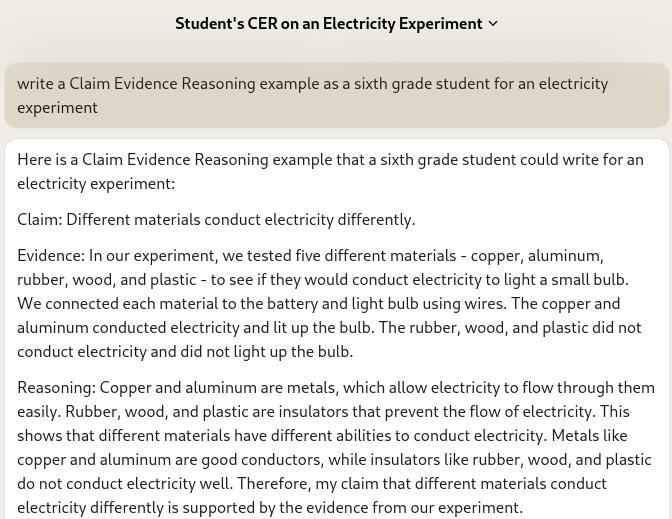

Now that we have access to content creation models like ChatGPT, what do they say CER is? That is, how have they amalgamated all the information out there to explain CER? Here’s what ChatGPT has to say:

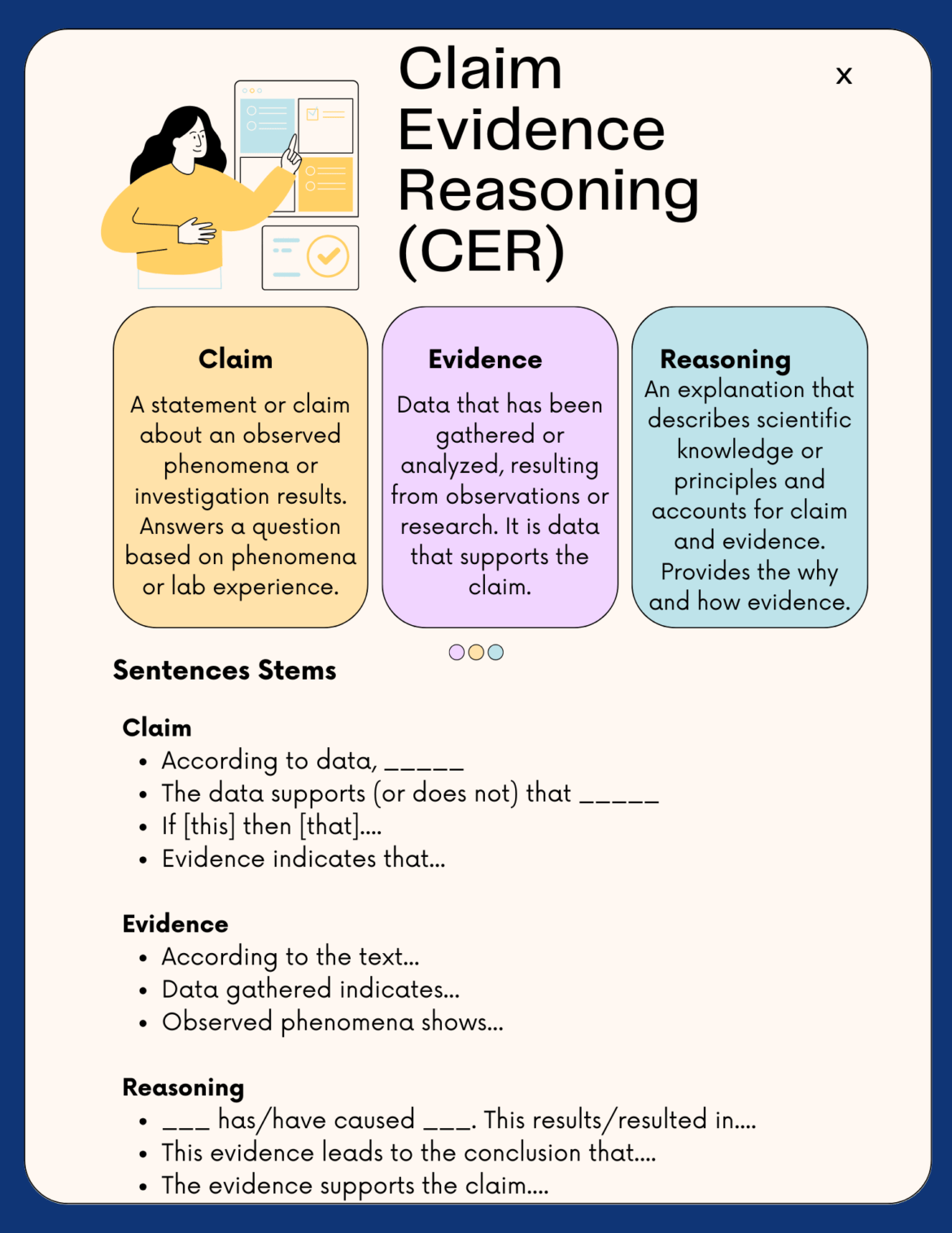

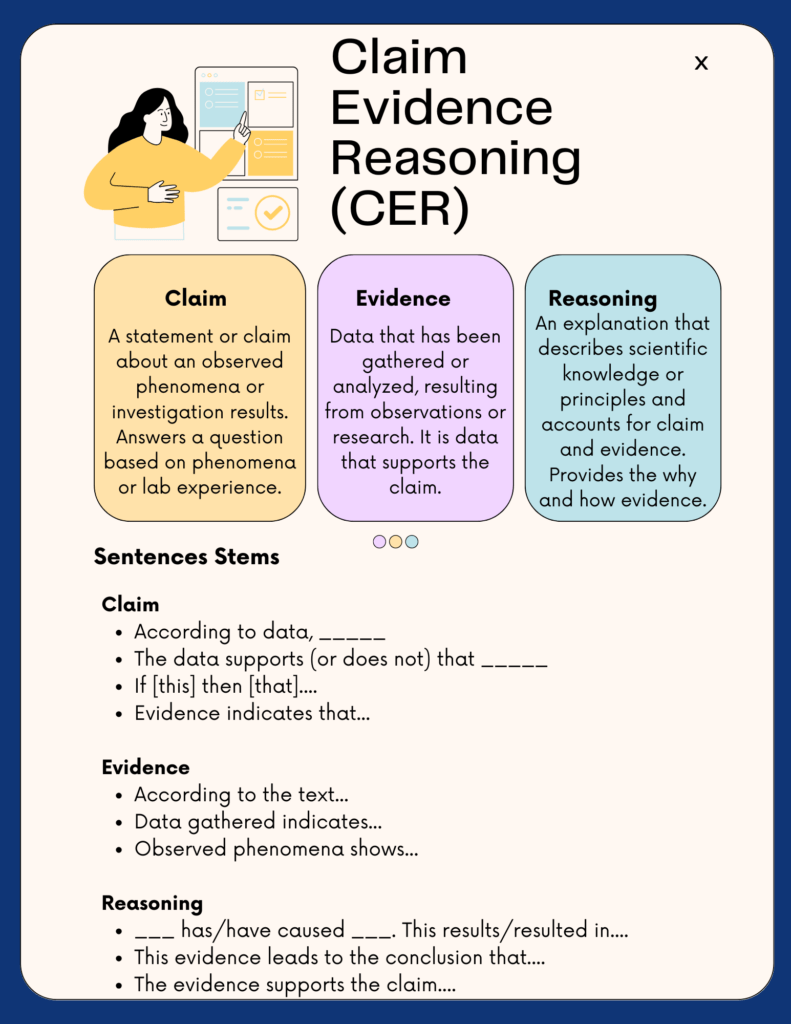

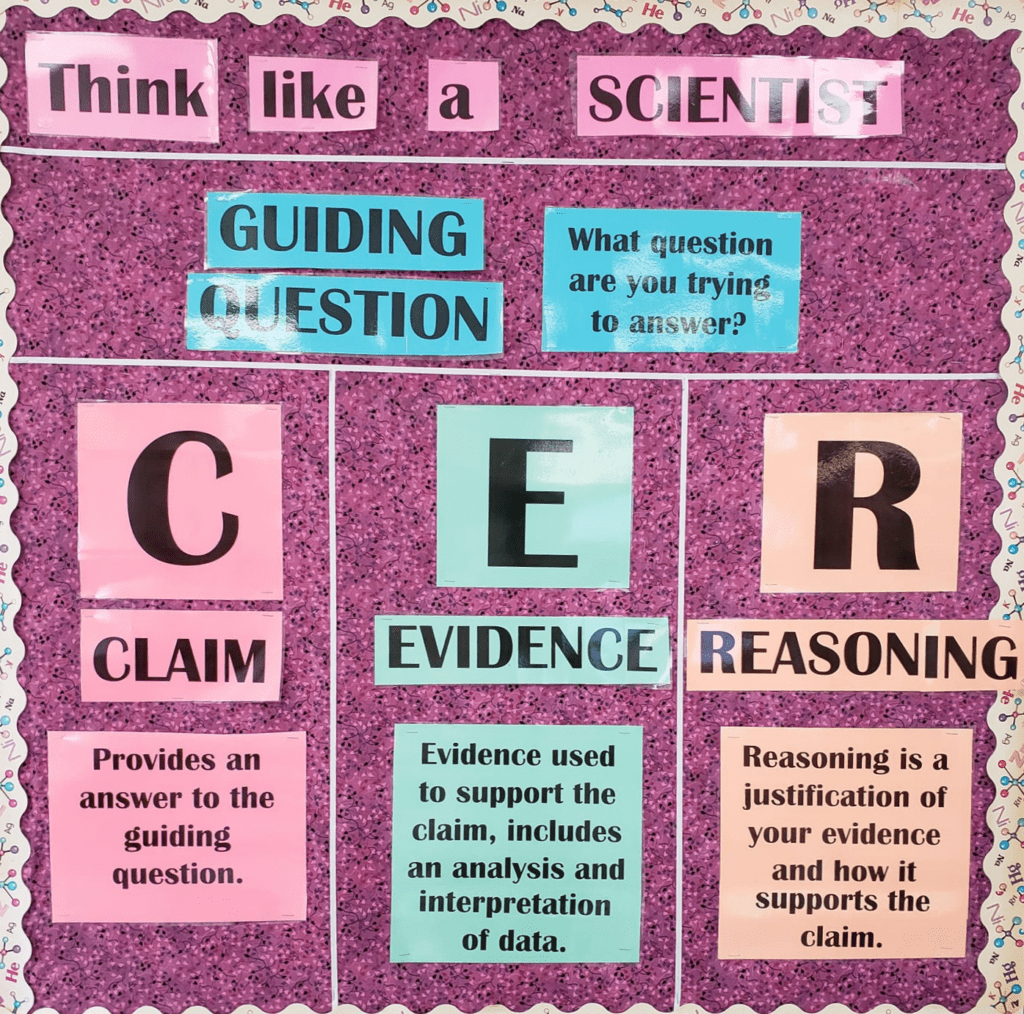

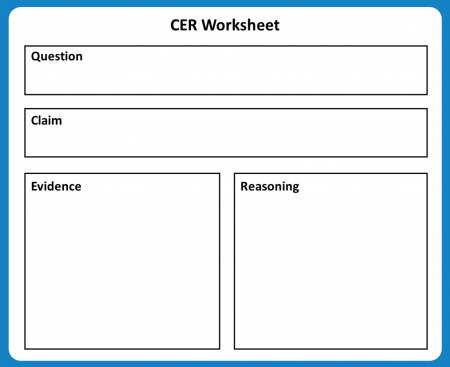

CER stands for “Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning.” It is a framework commonly used in scientific writing and argumentation to structure and communicate ideas and findings.

– Claim: The claim is a statement or conclusion being made. It is the main point that is being argued or asserted.

– Evidence: The evidence is the information or data that supports the claim. It can come from experiments, research studies, observations, or personal experiences.

– Reasoning: The reasoning is the logical connection or explanation that links the evidence to the claim. It explains why the evidence is relevant and supports the claim.

CER is often used in scientific investigations and writing to structure explanations and arguments, helping to ensure that claims are supported by valid evidence and logical reasoning.

As wonderful an explanation as that is, I thought I’d take a page or two from Scott Phillips’ free ebook: Writing in Middle School Science: Claim, Evidence, Reasoning Papers That Work.

When to Use CER

Scott Phillips shares that he uses CERs in two ways:

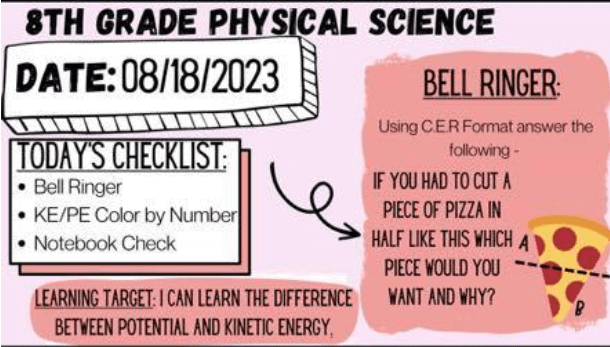

- Warm-ups at the beginning of class

- Tests and quizzes

This isn’t the only way you can use CER. You may already be familiar with bell ringers and why they are effective. Hannah Bain suggests using CERs as bell ringers. See her example below:

Getting Started with CERs

CERs appear in curricula like STEMscopes and in Texas Gateway. Of course, you can find it in many other places. These videos offer great places to start:

- An introduction for students to CER

- Claim Evidence Reasoning via Culturally Relevant Science

- How to Write a CER via Saginaw Chemistry

- CER and Equitable Grading and CER 6-8th Grade Progress and Rubrics

In his ebook, Scott Phillips shares this formula:

- Sentence 1: Answer the question

- Sentences 2,3,4: Convert data from number format into sentence format. Exclude unimportant data.

- Sentence 5: Start with “In science, we know…” then state the scientific principle that supports your answer.

- Sentence 6: Summarize data, then write “Therefore,” and summarize your answer.

“Avoid writing more than six sentences and do not use the word ‘because,'” says Scott Phillips in his book. Jennifer Weibert (see her slide deck in the “Additional Resources” section below) offers these steps:

- Re-state your claims.

- Provide some scientific principles/knowledge that you already have about a topic.

- Provide data from the activity (lab, gizmo, etc.) that connects to the scientific principles/knowledge mentioned in Step 2. Show that your data can be used to prove your claim.

- Wrap up your reasoning with a conclusion sentence that begins with a word such as “Therefore,” “Hence,” “Thus,” or “So,” and re-state the claim.

Another approach from Laurie ‘Cadwaller’ Johnson. Examples from Angela Kopp appear below each point:

- C- Claim. No explanation.

- The specimen under the microscope is living.

- E- Evidence. The most boring sentence (or sentences) that put(s) the info from a data table or graph (quantitative is best; qualitative is ok) into an understandable phrase.

- The specimen contains cells with a nucleus, cell membrane, and cell wall. When I looked at my cheek sample and onion sample, I saw cells with a nucleus, cell membrane, cell wall (onion). When looking at samples of salt and sand, no cells were present.

- R- Reasoning. The phrase that ran through your head when you looked at the data and the claim came to mind.

- All living things contain cells. Cells are the basic building block for all organisms.

- J- Justification. What information from a society (like the scientific community/research group) or entity supports you as well? Is there a science concept that also supports you outside of the evidence of the investigation?

- None provided.

Here’s another explanation you can view as a video (5 minutes and 21 seconds):

Another interesting way to think about scaffolding students’ thinking is to include questions. These questions assist student in developing a deeper focus for their question, any claims, and evidence.

Expanding Questions with the Science Writing Heuristic

Worthy of consideration is this heuristic. It includes some questions that spur thinking. You may have seen these questions below as part of the Science Writing Heuristic:

- Beginning ideas – What are my questions?

- Tests – What did I do?

- Observations – What did I see?

- Claims – What can I claim?

- Evidence – How do I know? Why am I making these claims?

- Reading – How do my ideas compare with other ideas?

- Reflection – How have my ideas changed? (source)

The use of the Science Writing Heuristic can facilitate “students to generate meaning from data, make connections among procedures, data, evidence, and claims.” It can also assist them in engaging in metacognition (source). These can definitely complement the use of CER in the classroom.

Let’s take a look at some more examples of CERs.

CER Examples

In one of many examples in his book, Scott asks, “Will the ball sink in water?” He later states you can ask this question in this way:

Which of these objects will sink or float in the water?

The information provided includes the density of three items. These items include:

- ball (1.5g/ml)

- water (1.0 g/ml)

- corn (0.25 g/ml)

Scott says the CER for these would be as follows:

- Yes, the ball will sink.

- The density of the ball is 1.5 g/ml

- The density of water is 1.0 g/ml

- In science, we know that a more dense object will sink in a less dense material.

- The ball is more dense than water, therefore it sinks.

He suggests that you can write this CER in paragraph form:

Yes, some objects will sink and others will float. The density of the water is 1.0 g/ml, while the density of the ball is 1.5 g/ml and the corn’s 0.25 g/ml.

In science, we know that more dense objects (ball) sink while less dense objects (corn) float atop the less dense material (water). Given that the ball is more dense, and the corn is less dense than water therefore the ball will sink and the corn will float.

Wondering how to introduce CER with easier examples? Let’s take a look at some of the responses from the Facebook group.

Examples from the Facebook Group

You can find these and more in the Middle School Science Facebook group. Some are humor-inducing and sure to engage students. Others explain sad events (e.g. the corn starch fire at a Taiwan Water Park in 2015).

A few select examples appear below:

- Use a murder mystery

- Give them an Encyclopedia Brown story to solve. (The Case of the Missing Clues.) Then, look at a case from Sherlock Holmes. It’s clear from these how evidence and reasoning are not the same. It helps students, but the skills don’t transfer easily to their own lab write-ups. Hard skill! Explain that in their labs, the reasoning is the science facts/concepts/laws and vocabulary that explain why what they are seeing makes sense.”

- Drops on a Penny. Count how many water droplets fit on a penny. Students take a guess how many will stay before it flows over.

- Oreo Cookie Stuffing. Are double-stuffed Oreos really double the filling?”

- Jelly Bean Nose Test. Does plugging your nose affect the flavor of a jelly bean?

- Quicker Picker Up Experiment. “My intro to the scientific method and CER this year began with taking notes on what each part of the scientific method was and then watching a commercial about Bounty paper towels. Students tested to see if Bounty really was ‘the quicker picker upper’.”

- Cold Water. Is the water cold? Students use a thermometer to measure the temperature to find it’s 10C. They make the claim that the water is cold. The evidence is that the water is 10C. The reasoning would be that temperatures lower than body temperature are cool or cold, and 10C is colder than body temperature. For each science investigation, there should be a problem in the form of a question or statement that students investigate. Students should be able to support their claim or hypothesis with the data they collect and explain why that data supports their claim

- Cornstarch CER. Demonstrate how cornstarch is not flammable unless in dust form. Then, show a news clip of the tragedy that occurred in Taiwan at the water park in 2015. Do a see, think, wonder list with their shoulder partners. Next, at their tables, they discuss each item; the other pair chooses one point that the other group made that they thought was interesting. They then asked that pair why five times concerning that point. It made them give much more information. When done, show them a picture of a color run and ask what they think. In the next class, complete a CER about it.

- My Dad’s a Space Alien. View this presentation and this video example.

- Fact-Checking the Internet. Focus on fact-checking the Internet and walk through your CER process. Be sure to check the list included in the Science Lessons That Rock resources in the “Additional Resources” section.

Finally, check out this amazing Wakelet Collection from Collette Taylor-Chovan:

Sentence Starters

Many of the science teachers in the Facebook group reported that they relied on sentence starters for CER. Here are a few I found that may be useful.

- The CER Sentence Frames handout and CER Drafting Tool via Sunnyvale School District

- Some CER Sentence Starters via ThinksRSD

- CER Paragraph Structure Reference Sheet via National Science Teachers’ Association (NSTA)

- CER Explanation with Starter Statements via Quincy Conference

Additional Resources

- Beakers and Ink from Carrie Troha Takarsh offers a Teach CER Like a Pro guide. It is free and becomes available after you subscribe to the blog. The guide is worth the subscription.

- Three Tier CER Scaffold

- Five Engaging Video Clips to Introduce CER

- BrainPOP Science on CER

- Science Lessons That Rock CER Video Examples

- Jennifer Weibert’s CER Introduction (slides)

- Using CER: Scientific Explanations to Increase Student Voice (slides)

- Model Teaching’s CER Checklist and Graphic Organizer