For many secondary and higher education students, Zoom has become a primary learning space. They log in, appear on a participant list, and are expected to engage as if they were sitting in a physical classroom. Yet instructors often encounter a familiar pattern: cameras off, long silences after questions, uneven participation, and students who seem present but disconnected.

Consider a composite student many educators recognize: they attend every Zoom session, rarely miss an assignment, and respond promptly to emails. In class, however, they never unmute. The pace of discussion feels too fast, the pressure to speak on the spot is high, and asking for clarification feels risky in front of peers. From the instructor’s perspective, the student appears disengaged. From the student’s perspective, the classroom itself has become a barrier.

The traditional approach to online teaching isn’t working.

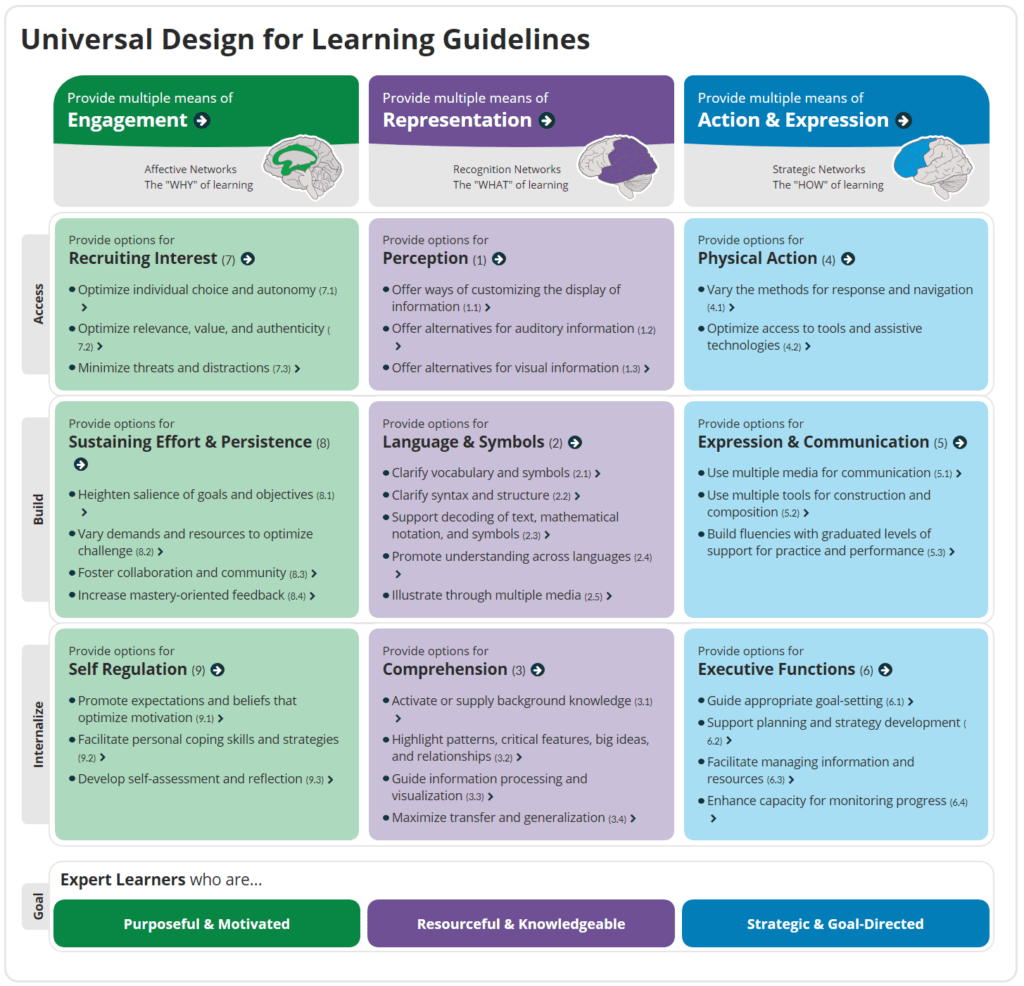

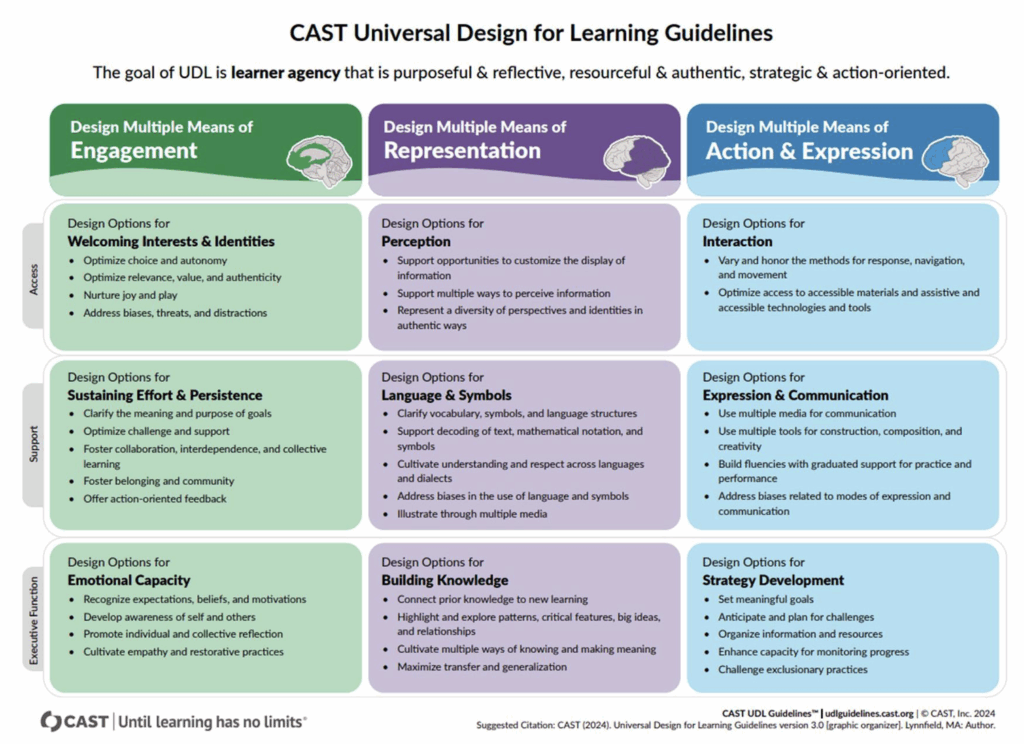

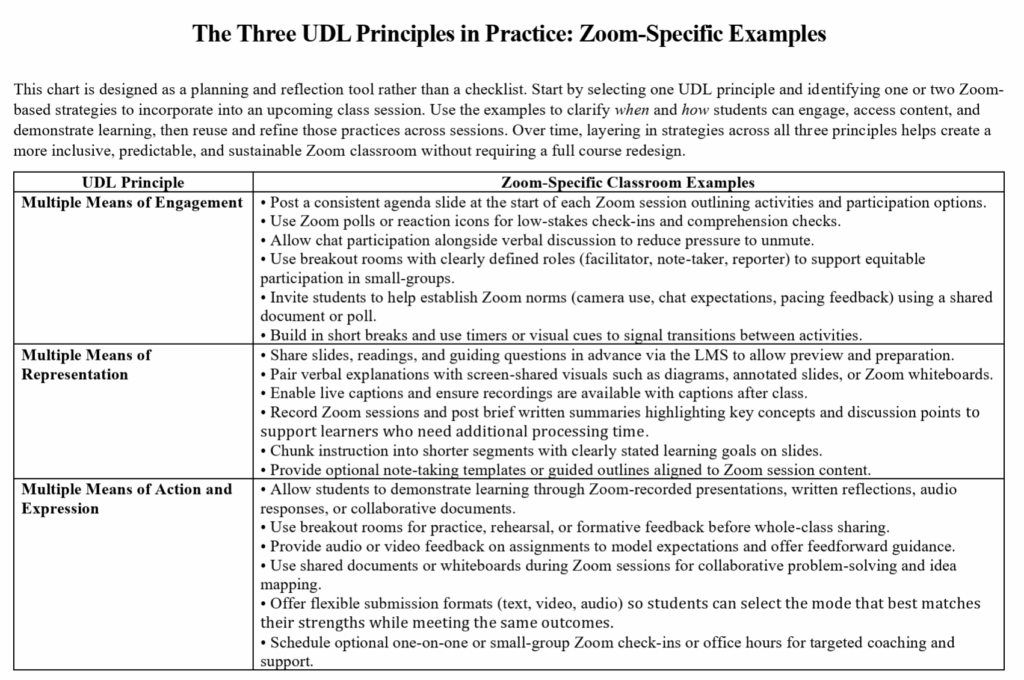

Traditional approaches to online teaching often assume that students will adapt to the environment: speak when called on, process information in real time, and demonstrate learning in a limited set of ways. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) addresses a different problem. Rather than expecting learners to fit a single model of participation, UDL focuses on designing Zoom classrooms that anticipate variability from the start. By building in multiple ways to engage, access information, and demonstrate learning, instructors can reduce common barriers that Zoom environments unintentionally create.

Grounded in research on how people learn, the CAST UDL framework emphasizes proactive design that supports learner motivation, comprehension, and expression. When applied thoughtfully, UDL shifts Zoom teaching away from reactive accommodations and toward inclusive practices that benefit all students, not only those who disclose specific needs.

Why Start with UDL in Zoom Classrooms?

Zoom introduces challenges that are less visible in face-to-face settings: camera fatigue, cognitive overload from multitasking screens, anxiety about being recorded, uneven access to technology, and reduced social cues. When instruction relies on a narrow set of behaviors such as speaking aloud quickly or processing dense slides in real time, these challenges can compound.

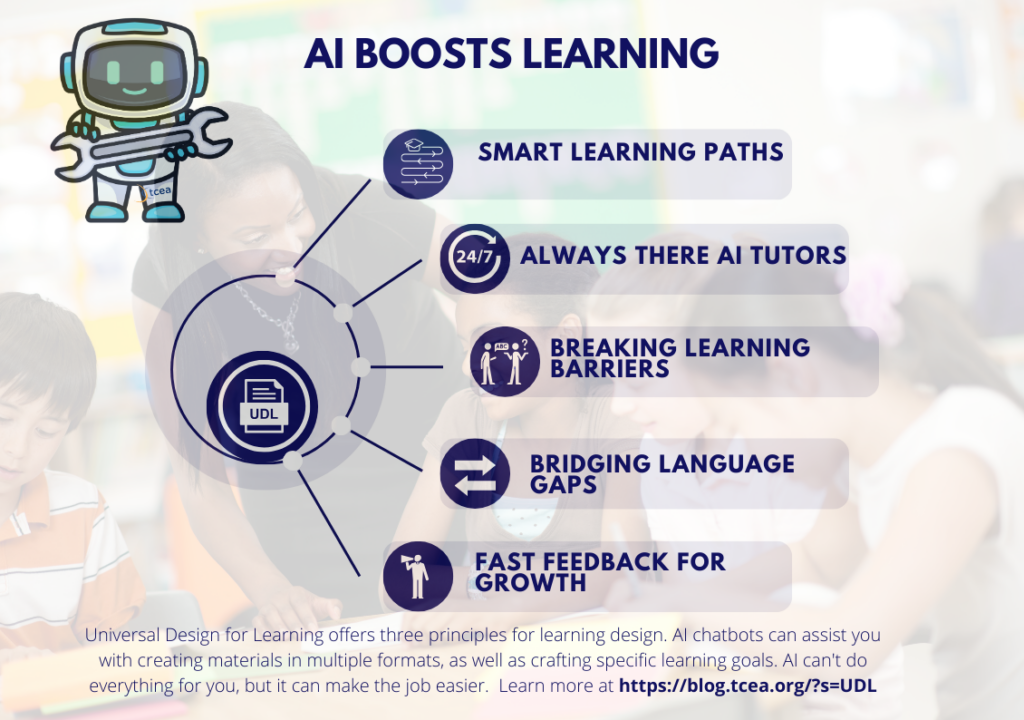

UDL offers a practical framework for addressing these issues by design. As articulated in the CAST UDL Guidelines 3.0, the three core principles, Multiple Means of Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression, align closely with common Zoom pain points. Together, they support learner agency, clarity, and flexibility while maintaining academic rigor.

Multiple Means of Engagement: Creating Stability, Safety, and Choice

The principle of Multiple Means of Engagement focuses on how learners connect with and sustain their learning experience. In Zoom classrooms, engagement is often affected by uncertainty, social pressure, and limited opportunities for low-risk participation.

Establishing Predictable Structures

Students are more likely to engage when expectations are clear and consistent. In Zoom, this means establishing participation norms and routines. For example, instructors can clarify when cameras are encouraged or optional, how students should ask questions (chat, raised hand, or unmuting), and what a typical class session looks like. Posting a brief agenda slide at the start of class and using Zoom timers or visual cues during transitions helps reduce cognitive load and anxiety.

Offering Multiple Participation Pathways

Zoom provides built-in tools that support varied forms of engagement. Chat responses, reaction icons, polls, annotate, whiteboard, and shared documents allow students to contribute without speaking aloud. Breakout rooms can be used for smaller, lower-pressure discussions, with clear roles such as facilitator or note-taker to support participation. These options align with UDL’s emphasis on reducing barriers related to social anxiety and self-regulation while maintaining active involvement.

Supporting Choice and Autonomy

Motivation increases when students have meaningful choices. In Zoom settings, this might include selecting discussion prompts, choosing between individual or group breakout rooms, or deciding how to contribute (verbally, in writing, or visually). Inviting students to co-create classroom norms or provide input on participation options further strengthens ownership and persistence.

Providing Feedback

Frequent, specific, and timely feedback is essential in Zoom classrooms, where students may otherwise struggle to gauge their progress or understanding. Instructors can use Zoom polls, reactions, chat responses, brief one-on-one breakout check-ins, or dedicated virtual office hours to provide formative feedback. Making expectations for when and how feedback will occur explicit, and inviting students to share feedback on pacing, clarity, and support, helps sustain engagement and self-regulation.

Once students feel supported and motivated to engage, the next challenge is ensuring they can clearly access and process course content in a fast-paced online environment.

Multiple Means of Representation: Making Content Accessible and Clear

Multiple Means of Representation addresses how information is presented so that learners can perceive, comprehend, and make meaning from it. In Zoom classrooms, content is often delivered quickly and verbally, which can disadvantage students who need more processing time or alternative formats.

Using Multimodal Instructional Materials

Effective Zoom teaching pairs spoken explanations with clear visual supports. Slides that highlight key points, diagrams shared via screen share, brief video clips, and annotated examples on whiteboards help reinforce meaning. Consistent slide layouts and clear headings make information easier to follow and revisit.

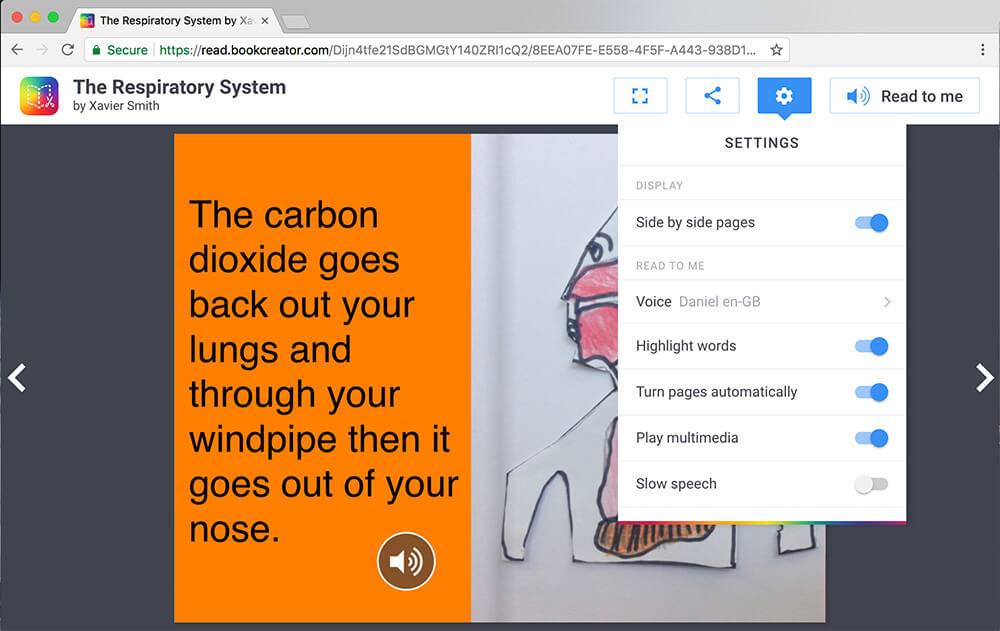

Leveraging Captions, Recordings, and Transcripts

Zoom’s live captioning and recording features are powerful accessibility tools. Captions support students who are deaf or hard of hearing, multilingual learners, and those attending from noisy environments. Recorded sessions, paired with brief summaries or discussion highlights, allow students to review material asynchronously and at their own pace.

Providing Structure and Advance Access

Sharing slides, readings, or guiding questions before class gives students time to preview content and prepare. Chunking instruction into shorter segments with clear learning goals supports comprehension and reduces overload. Optional note-taking templates or guided outlines can further scaffold understanding without limiting flexibility.

When learners are able to access and make sense of course content, they also need flexible ways to act on that knowledge and demonstrate what they have learned.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression: Showing Learning in Different Ways

The principle of Multiple Means of Action and Expression focuses on how students demonstrate understanding and build skills. In Zoom classrooms, reliance on a single mode such as written exams or live full-class presentations can unintentionally privilege some learners while constraining others.

Expanding Options for Demonstrating Learning

Zoom supports diverse formats for expression. Students can submit written reflections, record short video or audio explanations, collaborate on shared documents, or present in small breakout rooms rather than to the full class. These options align with UDL’s emphasis on supporting varied communication strengths and executive functioning skills.

Designing Flexible and Varied Assessments

Incorporating a mix of low-stakes polls, discussion posts, collaborative activities, and projects provides multiple opportunities for students to show progress. Allowing flexibility in format or timeline, when appropriate, reduces unnecessary barriers while preserving learning outcomes.

Supporting Skill Development Through Tools, Feedback and Feedforward

Clear rubrics, exemplars, and checklists help students plan and monitor their work. Zoom breakout rooms and shared whiteboards can be used for guided practice, peer feedback, and rehearsal before higher-stakes assessments. Effective Zoom instruction pairs feedback with feedforward; clear guidance that helps students improve future performance, not just evaluate past work. Instructors can use brief coaching conversations in breakout rooms, audio or video comments on submitted work, and recorded model responses to highlight next steps and strategies for improvement. By defining when formative feedback will occur (during drafts, practice activities, or low-stakes submissions) and how students can apply that guidance before higher-stakes assessments, educators support learner agency, strategic skill development, and growth across multiple modes of expression.

Making It All Work Together

Implementing UDL in Zoom does not require redesigning an entire course at once. The framework is intentionally flexible and scalable and small, strategic changes can have a meaningful impact.

Start Small

If you try only one thing next week, consider adding a chat-based check-in or poll alongside verbal questions. This single adjustment can immediately broaden participation and provide richer feedback on student understanding.

Design for Sustainability

UDL-aligned practices often save time in the long run. Recorded explanations, reusable templates, and consistent routines can be carried across semesters. What begins as an accessibility support frequently becomes a resource that benefits all learners and reduces repeated clarification.

Reduce the Burden on Students

When flexibility and clarity are built into course design, students are less likely to need individual accommodations or extensions. They can focus their energy on learning rather than navigating barriers or advocating for access.

Ultimately, UDL reframes Zoom teaching from a question of compliance to one of intentional design. By anticipating learner variability and leveraging Zoom’s features thoughtfully, educators can create online classrooms with multiple entry points, clearer expectations, and more authentic engagement. Inclusive design is not an add-on; it is an intentional approach to teaching grounded in how learning actually occurs. When instruction is designed this way, it supports meaningful learning for all students.

References

CAST. (2023). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0. CAST. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Coy, K. (2017). Post-secondary educators can increase educational reach with Universal Design for Learning. Educational Renaissance, 5(1), 27–36.

Johns Hopkins University. (n.d.). Hopkins Universal Design for Learning (HUDL). https://hudl.jhu.edu

Rao, K., & Meo, G. (2018). Inclusive instructional design: Applying UDL to online learning. Journal of Applied Instructional Design, 7(1), 19–33.