Recently, a school district administrator emailed me and asked, “If you were going to blend strategies that work into a science lesson, how would you do it?” That question really piqued my interest. Mixing instructional strategies that are proven to work with best practices in science teaching and learning sounds like a win/win. After much thinking, here’s how I would accomplish this, based on the research.

Step #1: Set Goals for the Science Lesson

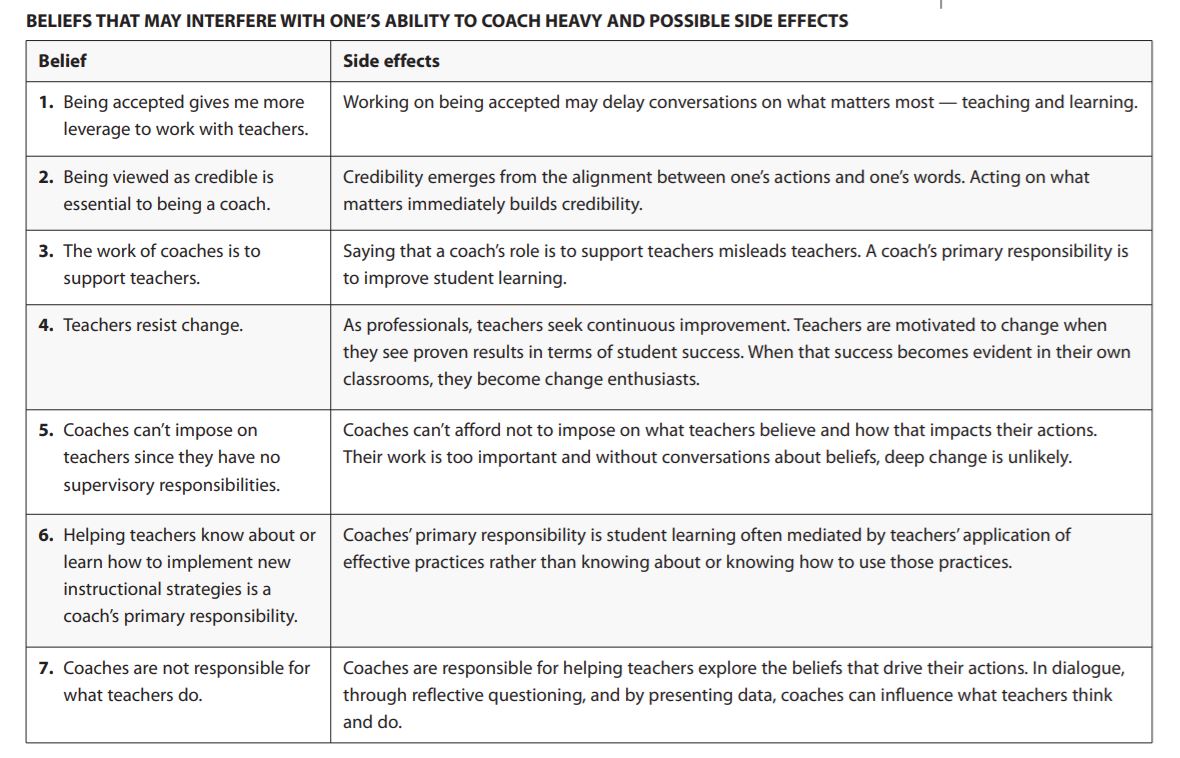

Dr. John Almarode, who wrote Visible Learning for Science, suggests setting the following goals for science lessons. The goals are straightforward and represent a wonderful response to the question asked.

- Get students interested in lifelong learning and science that works.

- Give students more control over their own learning.

- Build in ways to assess students to discover where they are, and then match strategies to what they need to learn.

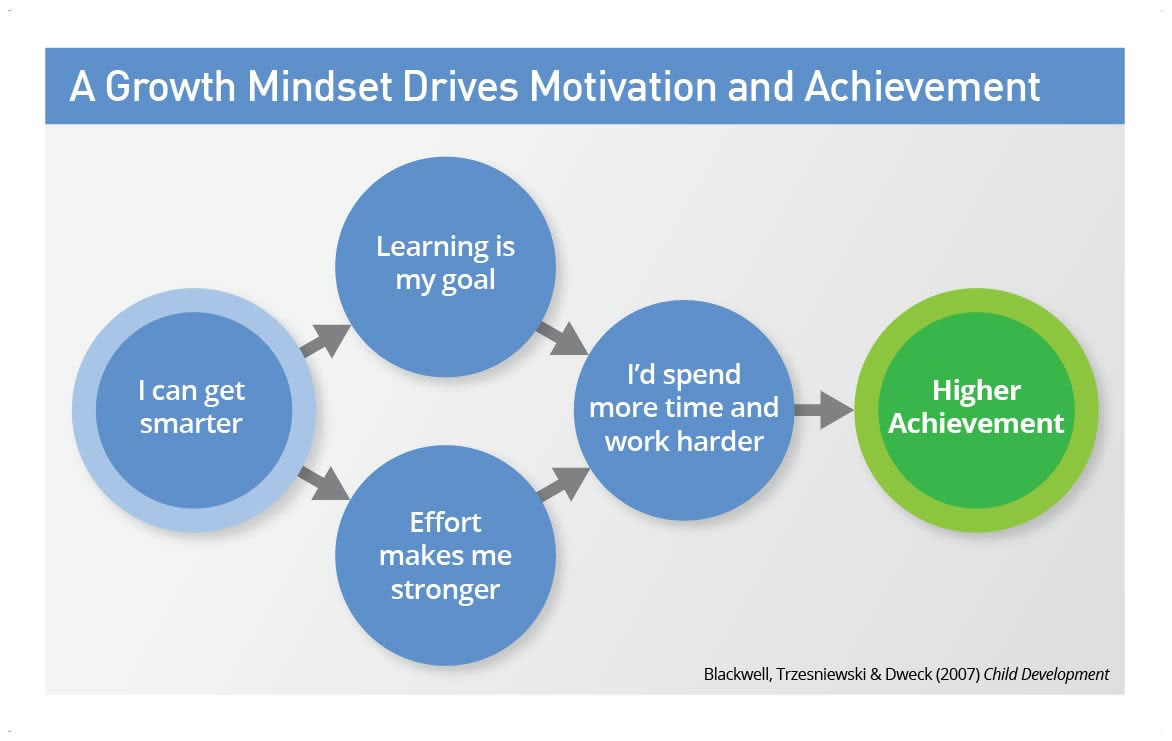

The first goal is practical and makes learning relevant to the learner. The second ties into John Hattie’s strong belief in the need for students to be self-regulated learners, individuals who must have agency and ownership over their learning and are able to track their progress. In tracking their own growth towards learning targets, they can make decisions, which gives them voice and choice.

Step #2: Pre-Assess Student Learning

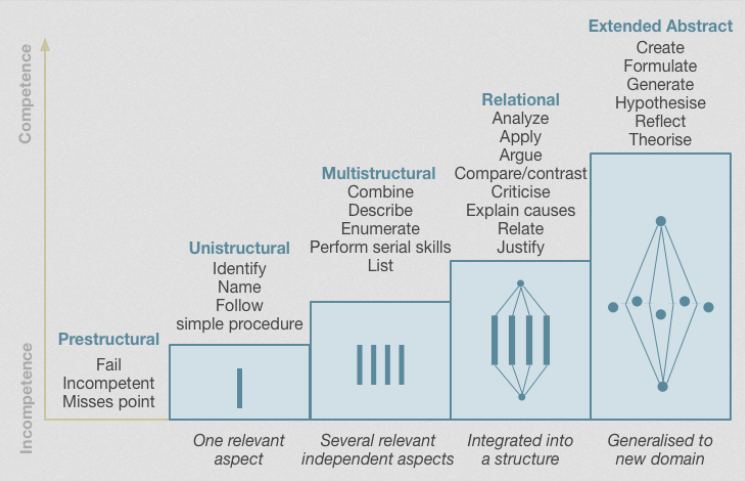

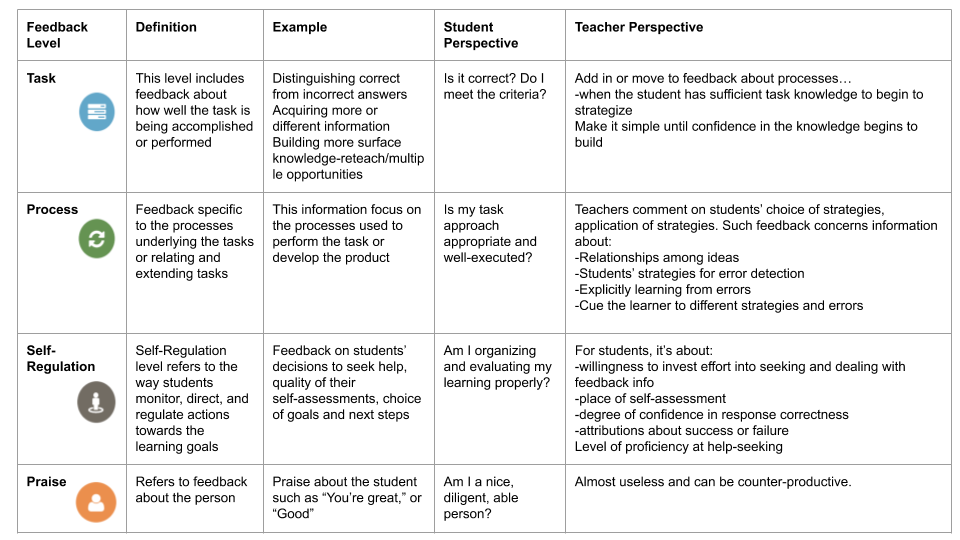

When determining what students already know about a topic or skill, you have to ask, “How do we pre-assess students where they are at?” This leads to the question, “What are some formative assessments we could use?” These assessments provide insights into where students may fall on the SOLO Taxonomy. SOLO stands for “Structure of Observed Learning Outcome.” This isn’t the first time I’ve mentioned SOLO, as have many others.

Let’s revisit what SOLO Taxonomy offers:

SOLO illustrates the qualitative differences. It indicates the differences between student responses and their levels of understanding. It classifies outcomes, relying on complexity and understanding.

SOLO does this so that you can make a judgement on the quality of student responses to assessment tasks. It relies on five levels of understanding:

Prestructural: at this level the learner is missing the point

Unistructural: a response based on a single point.

Multistructural: a response with multiple unrelated points.

Relational: points presented in a logically related answer.

Extended abstract: demonstrating an abstract and deep understanding through unexpected extension.

This FutureLearn chart clarifies the levels:

The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy (Adapted from Biggs & Tang, 2011) as cited in source

The main benefit of the SOLO Taxonomy is that it gives you, as the teacher, a set of specific terms (e.g., Unistructural, Multistructural, Relational) that can describe a student’s level of understanding. This level of understanding pinpoints what strategies may work best for them as they more through the learning process.

For students who are unistructural, they are in the surface phase of learning. This means that you might rely on those types of strategies, which could include vocabulary programs, direct instruction, and/or flipped classroom.

For learners who are relational, in the deep learning phase, different strategies work best. These may include concept mapping, metacognition, and reflection.

Knowing where a child falls on the taxonomy helps identify their level of understanding. It also assists you in knowing what to do next and to set success criteria.

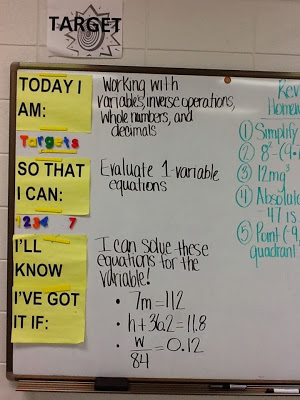

What Is Success Criteria?

This phrase involves students knowing and understanding the answer to a simple question. That is, “How will I know I have learned it?” It is sometimes expressed as a statement, “I’ll know I’ve got it if….” You may want to revisit COLOSO in this blog entry.

Step #3: Build Learning into the Science Lesson

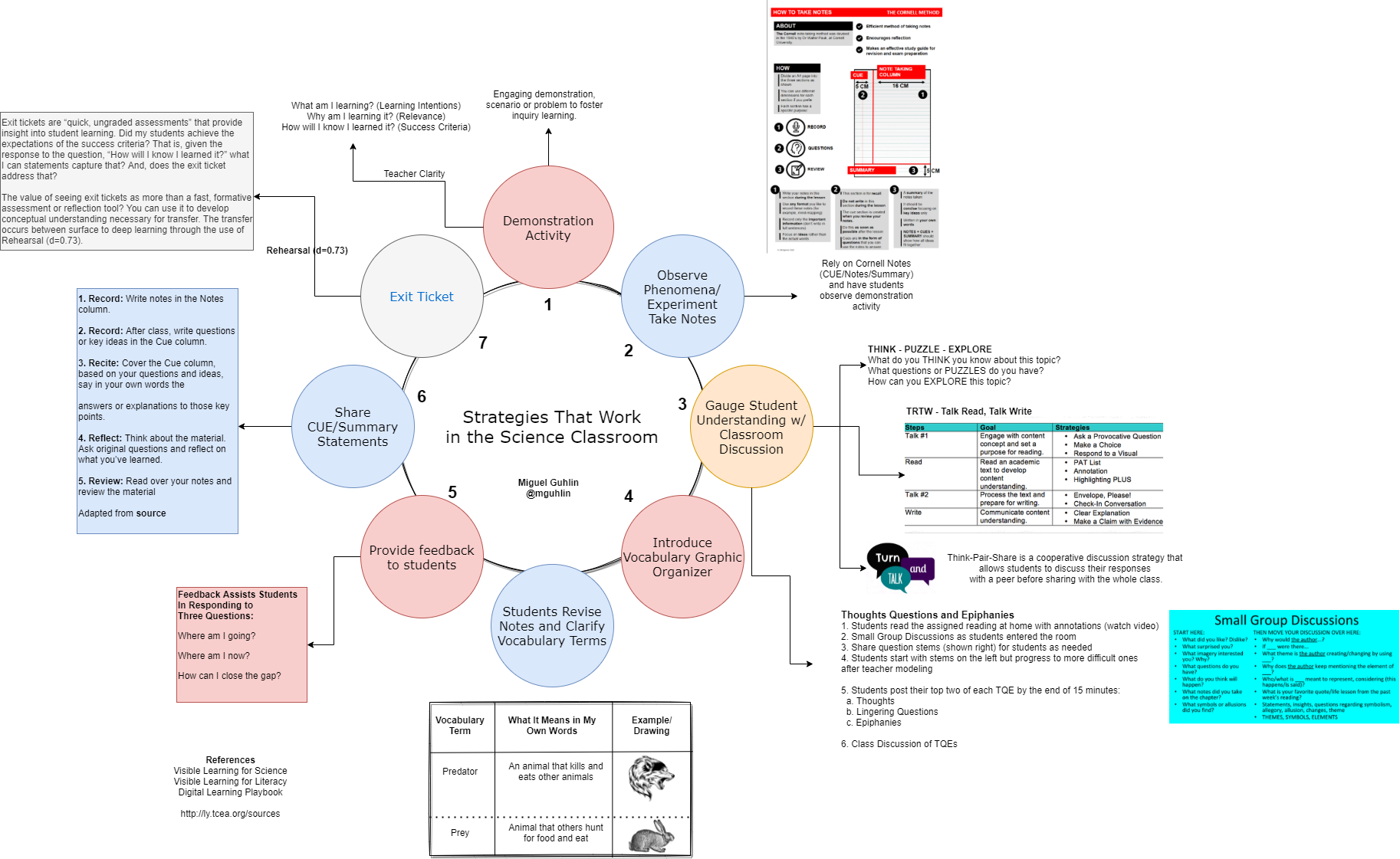

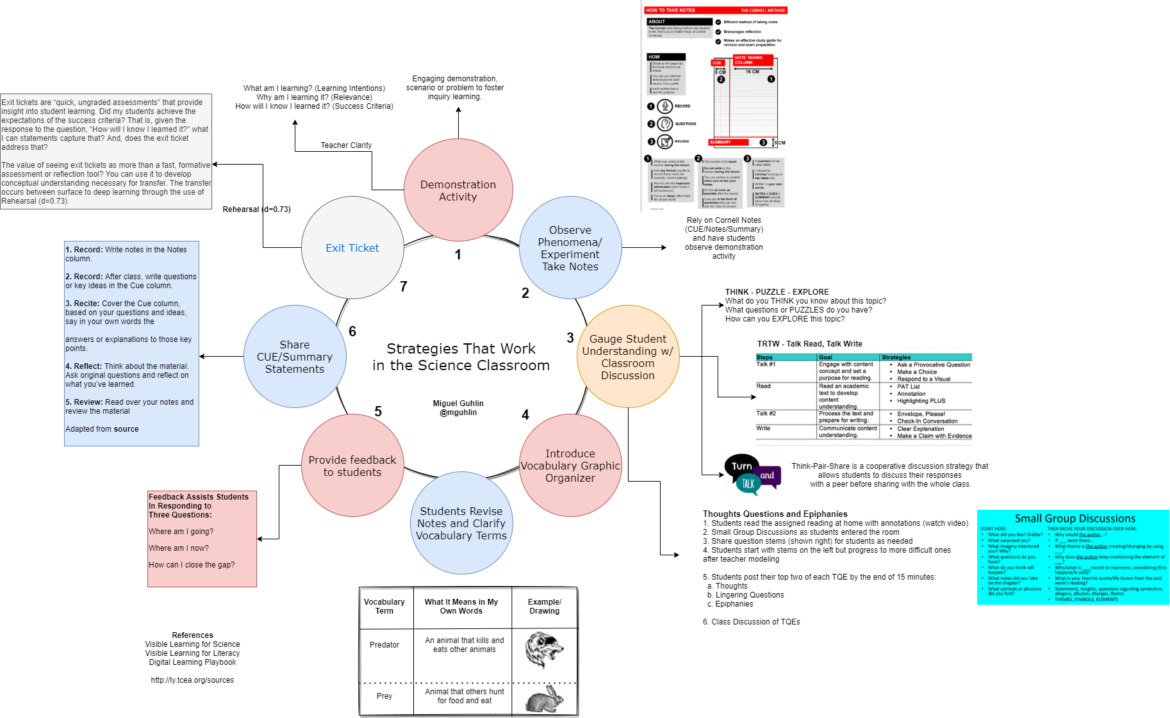

Ready to start on lesson design? Let’s take a look at the process Dr. John Almarode elaborates on. I’ve included a few resources for each area. What would you add?

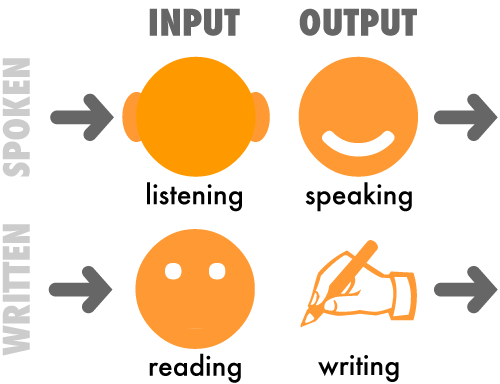

“Science education needs a mix of demonstrations, labs, and experiments. It also needs reading, writing, and discussing with other scientists,” says Almarode. To that end, the lesson process he describes looks like this:

a) Paired Demonstration and Writing Down Observations

- Demonstration

- Encourage students to write about what they observed

b) Clarifying Terms and Vocabulary

- Discussion about vocabulary terms

- Have students revise their writing using correct terms

c) Wrap-Up

- Final wrap-up

One key point that jumped out at me?

Every lesson (surface, deep, transfer) needs to have a clearly articulated learning intention. That learning intention must connect to success criteria. Remember, that is “What am I learning?” (learning intention) and “How will I know I have learned it?” (success criteria).

That’s quite a jump. To help the process make more sense, I put this diagram together that captures my understanding. Don’t be afraid to share your version.

Get a copy of this image via Google Slides or via Diagrams.net (requires you to authorize Diagrams.net in Google Drive account).

As you can see from this diagram, there’s a lot going on. To complicate matters, I’ve included some additional tools and strategy suggestions. How would you approach lesson design in your classroom with these three steps?

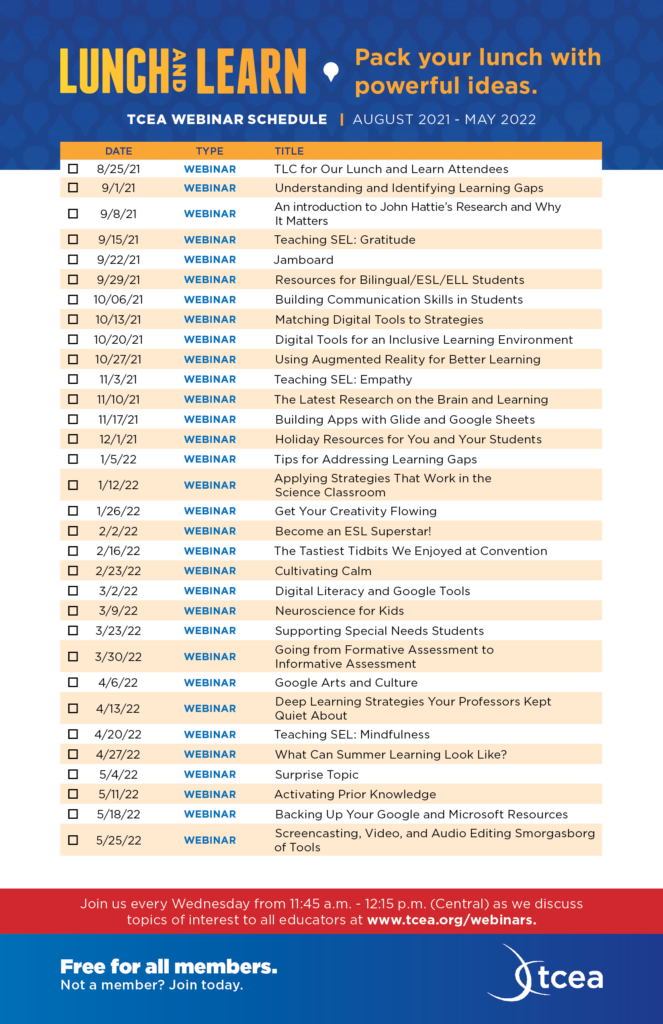

Matching Process to Resources

To provide some support, please find some relevant resources organized by the step in the process. I’ve organized them into a meta-collection in Wakelet. Explore and have fun.

Access this Wakelet Meta-Collections online at https://tinyurl.com/stwscience

Feature Image Source

Photo by author.

In addition, there will be really fun Bitmoji activities happening in the TCEA Membership Booth each day that you won’t want to miss. Whether you are a Bitmoji veteran or have yet to create your own avatar, stop by, and learn how to up your game and showcase all that you’ve learned during TCEA 2021. There will be daily lessons, tons of resources, and so much fun!

In addition, there will be really fun Bitmoji activities happening in the TCEA Membership Booth each day that you won’t want to miss. Whether you are a Bitmoji veteran or have yet to create your own avatar, stop by, and learn how to up your game and showcase all that you’ve learned during TCEA 2021. There will be daily lessons, tons of resources, and so much fun!