When you think about how to help teachers become even better at the art of educating young minds, the task can seem daunting. How do you individually work with what is usually a large number of teachers so that each one improves in at least one area that directly impacts student learning? And how do you do that when there is limited time for their professional learning? For some districts, they’ve made the decision to not even try and are eliminating the instructional coach and the instructional technology coach positions. But is that a good move? What does the research say about the impact that instructional coaching can have on teacher performance in the classroom? How should instructional coaches be used to get the most results? Let’s explore all of these questions in today’s blog.

What Is an Instructional Coach?

An instructional coach, whether for content-specific areas like ELA and math or for digital learning with the use of integrated technology, is a trained expert that works regularly “with teachers individually, to help them learn and adopt new teaching practices, and to provide feedback on performance. This is done with the intent to both support accurate and continued implementation of new teaching approaches and reduce the sense of isolation teachers can feel when implementing new ideas and practices (source).” It’s important to understand that, while coaches work with teachers, their ultimate goal is to improve student learning. That must always be the focus.

What Does the Research Say about Instructional Coaching?

There has been a lot of research done recently on the value that coaches can bring to student learning.

- Dr. John Hattie found that when instructional coaching is conducted over time in conjunction with data team analysis of how students learn, student growth is positively impacted. Both the coaching and the analysis must be done, however, to specifically inform instruction.

- The Effect of Teacher Coaching on Instruction and Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of the Causal Evidence found that instructional coaching had a greater impact on instruction than almost all other school-based interventions including student incentives, teacher pre-service training, merit-based pay, general professional development, data-driven instruction, and extended learning time. In fact, they determined the quality of teachers’ instruction improves by as much or even more than the difference in effectiveness between a new teacher and one with five to 10 years of experience. Similarly, student performance improved with instructional coaching regardless of whether a teacher was a novice or veteran.

- “Across instructional coaching studies by Jim Knight and Galey, there is consensus that instructional coaches need to combine teaching and content expertise with strong interpersonal and organizational abilities as coaches attempt to improve teachers’ practice while navigating complex relationships between policy mandates, school administrators, and wary teachers (source).”

- The New Teacher Center found that effective instructional coaches are those who are able to build relationships with teachers, understand good teaching practices, have experience with adult learners, and know how to use data.

- “Kraft, Blazar and Hogan found that there is significant evidence to show that a high-quality coaching experience can improve a teacher’s skillset. In fact, gains seen from high-quality instructional coaching were equivalent to the gains seen in teacher experience learned over five to 10 years (as compared to a first year teacher). The impact did not end with teacher skill development. There was also evidence of a value-added effect on student achievement from teachers who had a high-quality instructional coach (source).”

How Can Instructional Coaching Be Maximized for the Greatest Learning?

The research indicates that there are some things districts can do to maximize results with coaching.

- A serious consideration is how many teachers one instructional coach can effectively support at one time. Districts may want to limit the ratio of teachers to instructional coaches, as well as leverage technology to take advantage of virtual coaching. Research found there was little difference in the effectiveness of coaching programs online versus face-to-face.

- “The national coaching survey shows that coaches throughout the country serve in multiple roles both within and outside the classroom. Moreover, they support large caseloads of teachers, which results in spending less time with each teacher. This situation may diminish the effectiveness of coaching programs (source).”

- In addition to coaching resources and training, coaches benefit from access to ongoing mentorship.

- In larger school districts, large-scale coaching programs are less effective than smaller ones. This is consistent with the theory of diminishing effects as programs are taken to scale. “Districts may benefit with starting small, involving teachers who have a desire and motivation to participate, and tailoring coaching to individual needs. Larger programs requiring mandatory participation that are not individualized may be less effective especially if the teachers are not invested in the coaching process. However, it’s important to note that even larger coaching programs had meaningful and statistically significant impacts on student achievement (source).”

- One study focused on the factors that influence responsiveness to coaching, especially with teachers who appeared the least receptive to collaborating with a coach to support the implementation of a new practice. Results highlight the patterns and complexities of the coaching process for 20% of the teachers in the study who were categorized as resistant to coaching, suggesting that the one-on-one model of coaching offered in this study may not be the best fit for all teachers.

- Kane and Rosenquist (Making the Most of Instructional Coaches, Kappan, April, 2018) share that while the promise of coaching is high, the evidence of effectiveness has been inconsistent. Coaches’ job descriptions may be one of the problems. They often contain a wide array of duties that can erode time to work directly with teachers. Studies have identified some coaches working only a fourth or a third of their time with teachers to improve instruction.

Are You Coaching Heavy or Light?

The first article in this newsletter discusses the difference between coaching that actually changes practices in the classroom (coaching heavy) and what often happens with instructional coaching (coaching light). Coaching light duties may include “testing students, gathering leveled books for teachers to use, doing repeated demonstration lessons, finding web sites for students to use, or sharing professional publications or information about workshops or conferences.” The author says that while these are all worthwhile endeavors and do result in teachers forming a closer relationship with the coach, they do not usually result in improved student learning.

“Coaching heavy, on the other hand, includes curriculum analysis, data analysis, instructional changes, and conversations about beliefs and how they influence practice.” It is a much harder job and may not result in forming a closer relationship with a teacher. Coaching heavy may cause both the teachers and the coach to question their actions and decisions and may leave them feeling on edge. It includes asking thought-provoking questions and engaging in dialogue with teachers “about their beliefs and goals rather than focusing only on teacher knowledge and skills.”

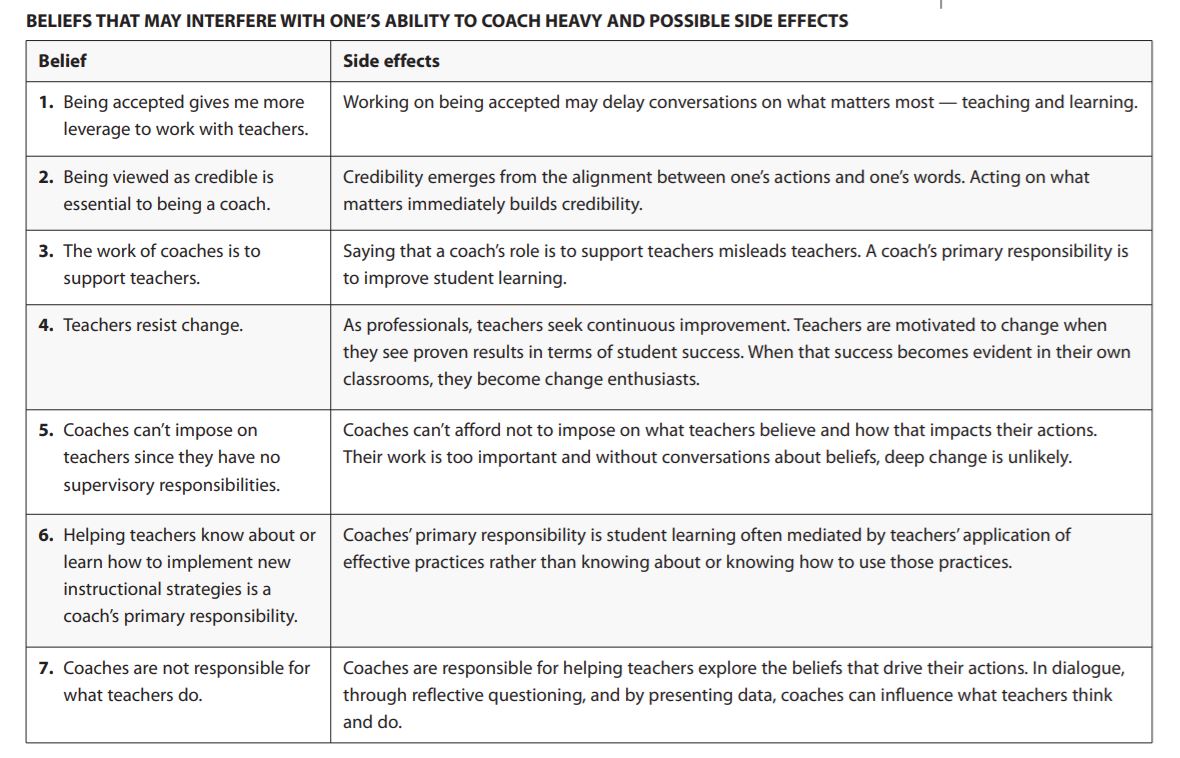

The table below shows the beliefs that a coach may have that may negatively impact his/her ability to coach heavy and the resulting side effects.

After further thought and research, the author found that effective coaches use a mixture of both light and heavy coaching. Coaching light is done primarily at the beginning of the new coaching period, like the start of school, and lasts for several weeks. Coaching heavy takes up after that and continues throughout the rest of the school year.

Key Takeaways

So what should our takeaways about instructional coaching be? Does it make a difference in improving teaching and learning? How can we structure it so that it is most effective?

- Instructional coaching for content areas and digital learning can make a significant difference in student achievement.

- Coaches need to be experts in both their content area and in best practices in pedagogy. They must also stay current with the latest brain research on learning.

- Coaches need to focus on holding dialogues with teachers on their beliefs and practices.

- District should make sure that coaches have time for the heavy duties by eliminating many of the other duties often assigned to them such as testing, textbook inventory, and subbing when teachers are out.

What does your instructional coaching program look like? How might you improve it? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments!