Explore resources, tools, and strategies for teaching STEM and STEAM. Discover innovative ideas to engage students in science, technology, engineering, arts, and math.

When they’ve been swirling around in my head, words never seem to come out the way I intend them to. Writing and getting ideas down on paper has always been a struggle for me. Even for this article, I’ve spent so much time thinking about what to write instead of just writing it all down! The prewriting process can be a challenge for adults, so it must also be for some of our students.

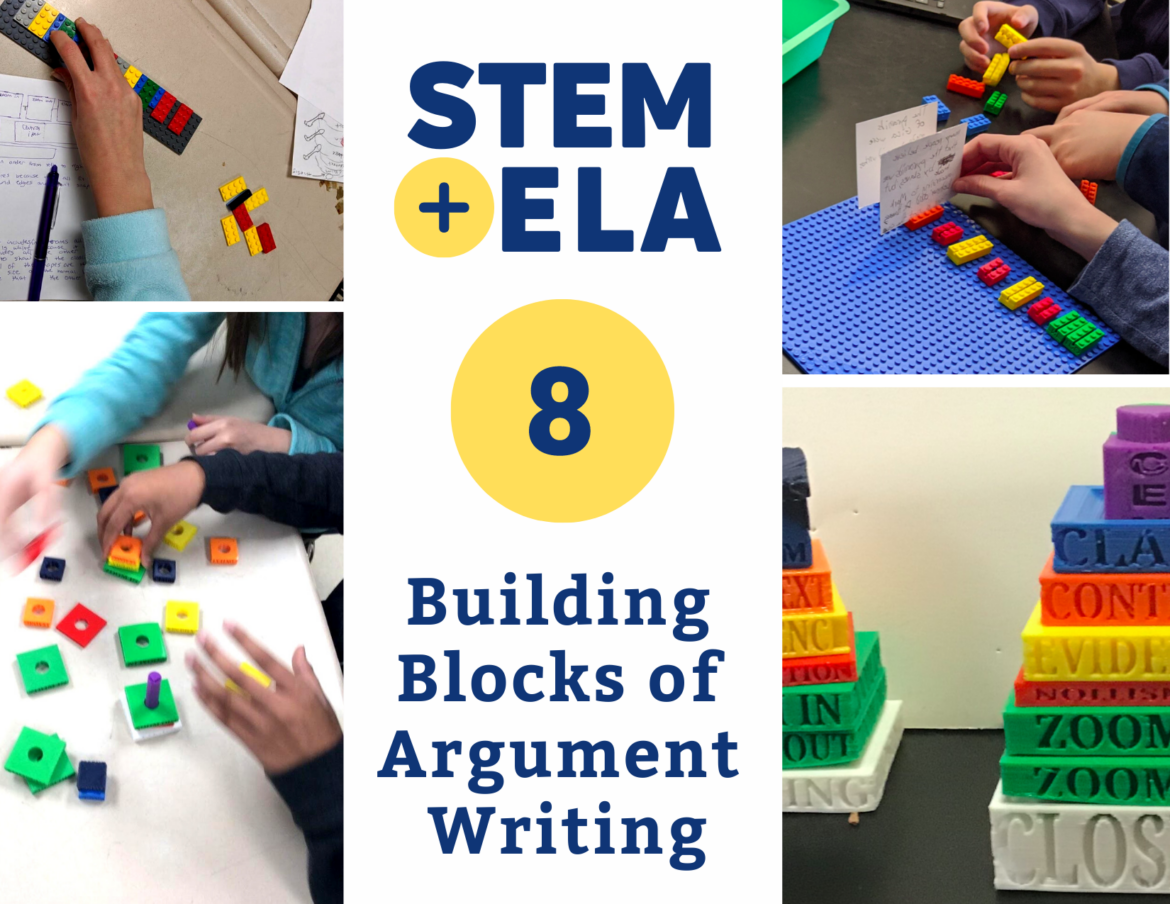

An ELA and STEM Collaboration

I’ve always been a good builder and engineer. And the idea of being able to physically “build” an essay before writing it appealed to me. I could see this as a way to help students get their ideas organized before diving into the task. So after a teacher-led “unconference” about merging engineering and other content areas, I met with an intrigued English teacher who wanted to approach writing differently in her class.

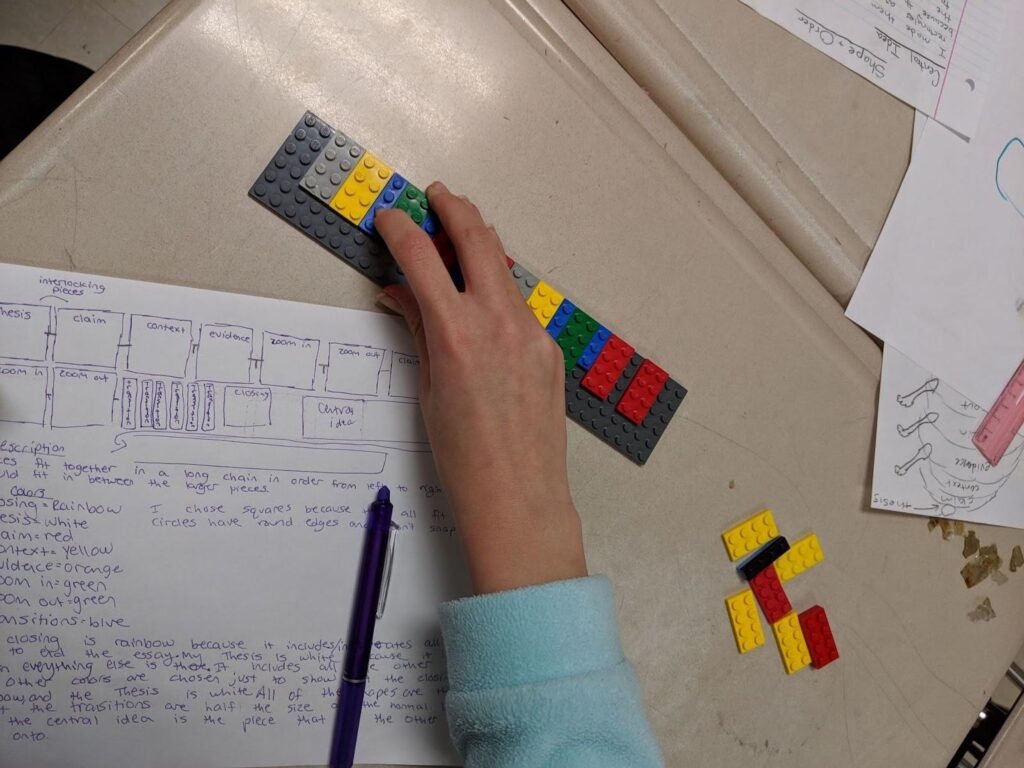

After a lot of brainstorming, drawing, erasing, sketching, lego construction, and laughter, we landed on a way to make students’ thinking and planning for argumentative writing visible and tangible in English class: 3D-printed blocks.

Organizing Writing Through Building

Students were learning about the foundational elements of argumentative writing, but they were struggling to understand the correct way to structure an argument. As a result, it was difficult for them to see how all the “parts” of the argumentative piece worked together to form a cohesive presentation.

To bolster student comprehension and confidence, we wanted to create an opportunity for them to literally construct their argument and then get feedback from the teacher before writing the first draft. We were determined to create an engaging, hands-on learning experience for students to help them plan and revise their writing.

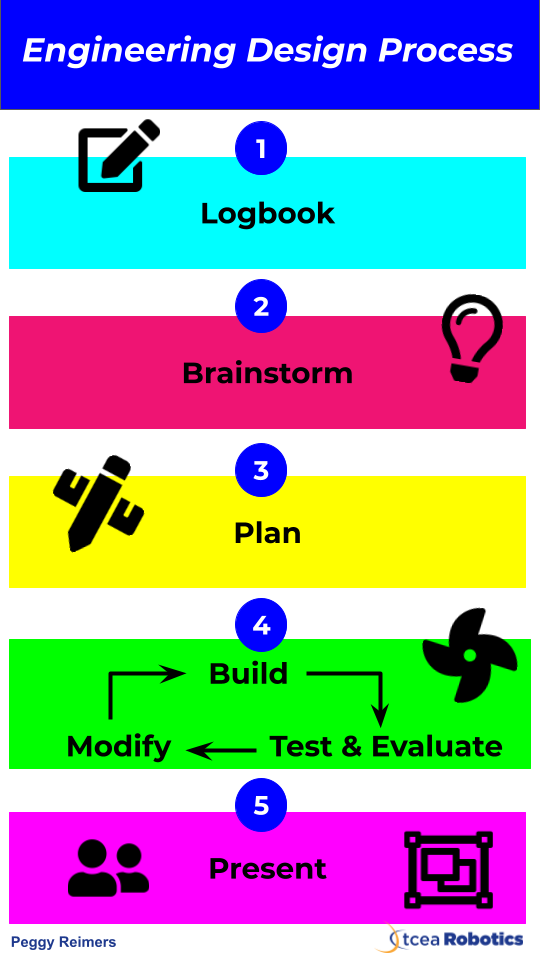

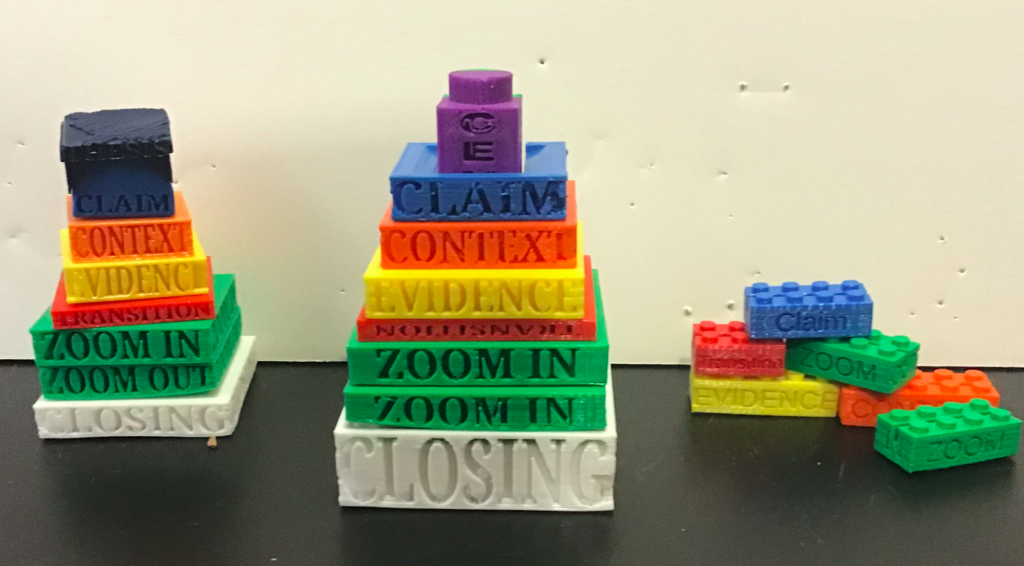

We broke down argumentative writing structure into the following parts:

- Central Idea

- Thesis

- Claim

- Context

- Evidence

- Zoom In/Out Analysis

- Conclusion

We knew that to help make students’ thinking visible, we had to be deliberate with our design and color choices. So we made our decisions based on the different parts of an argument, their purpose, and their relationship within the argumentative writing structure.

Colors were intentionally chosen to both highlight function and relationship to other parts of the argument. For example, the thesis was built to only fit into a claim piece because they are dependent on one another within the argument. The transition was designed as a smaller, red block because it should be a noticeable, short phrase that links two ideas together. The context was designed to fit between the claim and evidence. The central idea became a spindle since it is “the core” of the argument.

The STEM and Writing Mini-Unit

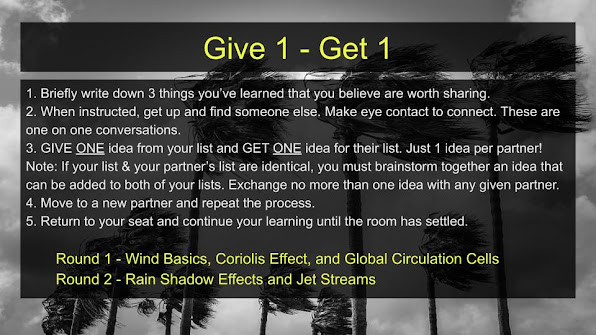

We planned for our two-week, co-taught, mini-unit to be broken down into eight lessons.

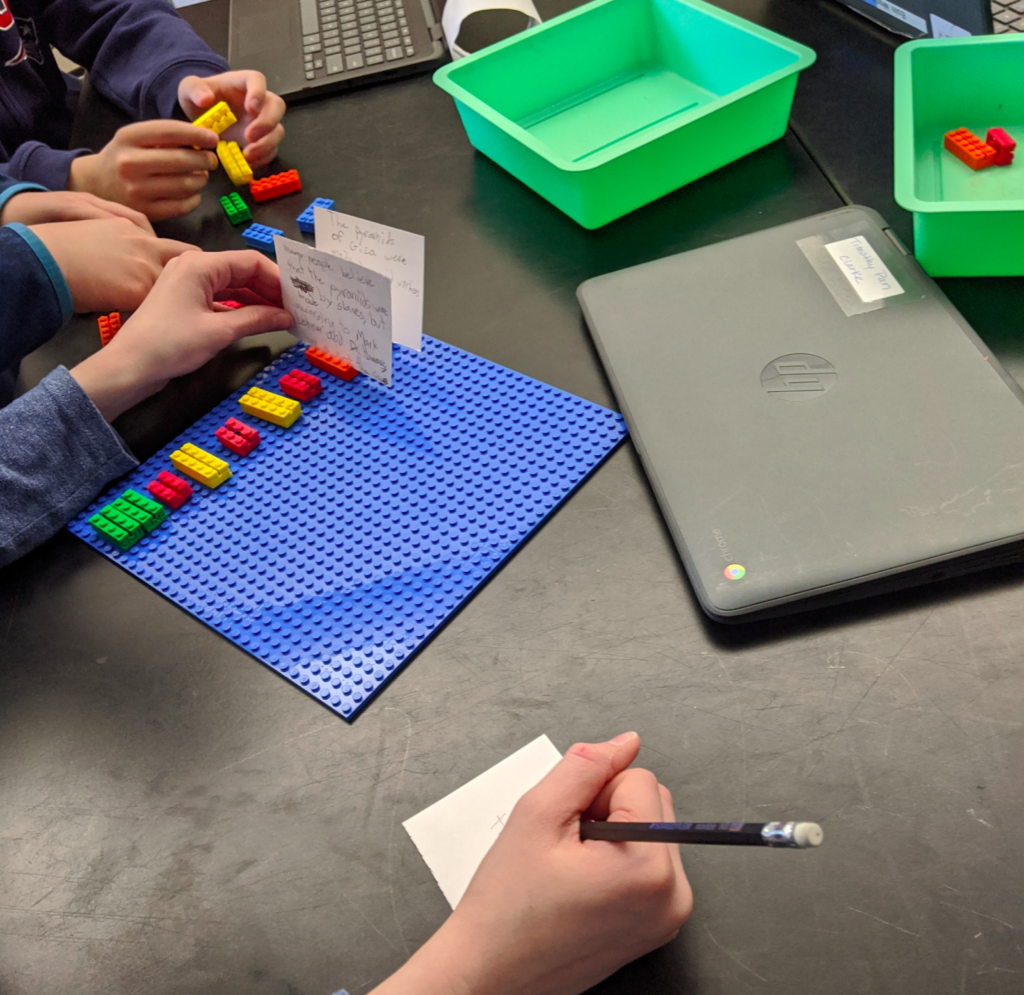

First, students were exposed to the argumentative writing vocabulary and how the parts of an argumentative essay worked in relationship to each other. After becoming familiar with the vocabulary and parts, they were given the blocks and an argumentative mentor text. They were asked to “build” the argument based on how the author structured it on the page. After building, students compared their argumentative “towers” with their peers while we circulated and gave feedback on their structures.

After getting teacher feedback and practicing with mentor texts, students began writing their own drafts, using the blocks for support. Then, with a partner, they participated in a peer review activity using their rough drafts. They were asked to build their partner’s essay using the blocks. From there, they gave each other feedback on their text structure about what was strong, missing, unnecessary, or out of order.

We then, as teachers, shared our design process for the blocks with the students, explained our reasoning behind the design decisions, and asked students for feedback on our designs.

The result? They gave great feedback, encouraging us to:

- Modify the blocks to allow for a notecard with writing to be inserted

- Create different shapes

- Ensure better fitting pieces

- Reconsider color choices.

We tasked them with designing a better version. Afterwards, students used the upgraded design to work on constructing their final drafts.

Reflections on the Unit

We observed that students were invested in the lesson in a way they hadn’t been with writing before. They enjoyed having the ability to physically manipulate objects to assist them in the writing process. The color choices and block fittings also helped them interact with the writing differently. They truly internalized the function of various parts of a written argument. We heard things like, “You can’t have a thesis there because the blocks don’t fit together,” and “The central idea is missing. See, your argument is just falling apart!”.

There were several light bulb moments from the kids, and they began to speak confidently about the connection between the blocks and their writing. We heard, “That makes sense. Transitions should be short because their job is to take you to the next part!” and “The conclusion should have a little bit of everything in it, because it’s white, and white has a little bit of every color in it.”

Perhaps the most valuable part of the lesson for us was when we described our planning process, and decision making to the students and then handed them an opportunity to design their own, better model. Partnering with the students to bring their writing to life not only helped them deeply internalize argumentative writing but also forged an invaluable learning partnership between us teachers and the kids. It opened a critical dialogue about how students learn best and deepened students’ confidence and trust in themselves and their teachers.

About the Authors:

Erik Murray (left) is a Middle School STEM teacher in Lexington, Massachusetts. His focus has been on making simple, hands-on activities. You can follow him on Twitter at @mrstemurray.

Casey Siagel (right) is a middle school English department head and ELA teacher in Lexington, Massachusetts. She is passionate about making reading and writing accessible and meaningful for all students.