I recently read Dr. James Loewen’s book, “Lies My Teacher Told Me.” With this book, I saw my illusions of history crumble. During my high school history classes, I loved the stories Brother Blake and Brother Sobel at Central Catholic High told. Unlike others in class, I made straight 100s on pop quizzes and tests. And like many Americans, I never gave those stories another thought.

History’s truths weren’t reflected in what I learned in history class, though.

I discovered these when reading works like Clint Smith’s “How the Word is Passed” and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s “An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States.”

Teaching History Today

Now, in the midst of talks of banning books and tensions surrounding what can be taught and can not be taught, it’s not an easy time to be a history teacher. How do you teach the truth about history and meet the state standards using secondary sources that may or may not be factual? With this question in mind, I asked a regional education specialist as we sat at an Exhibit Hall table during TCEA 2022 Convention and Exposition. I’ve changed her name to keep her anonymous, and I will refer to her as Kristin.

Recommendations for Teaching History

“What’s the best approach, Kristin?” I asked.

“Want to teach history? You have to realize it’s a lot of ground to cover,” she said. “And teachers are legally required to teach the TEKS.”

“But are the textbooks even accurate? In these times, how can history teachers ensure they’re aren’t teaching stories that fall short of the truth?” I countered. Textbooks fall into secondary sources that retell and interpret events.

“Teaching out of a textbook…robs the students not only of critical-thinking skills, but also of the richness of history, and the other voices that are there,” says history teacher, Liz Ramos. (source)

Kristin recommends:

- Focusing on a specific period, relying on the TEKS to guide you, and using tools like these:

- Encouraging cooperative learning and classroom discussions

- Defining key vocabulary

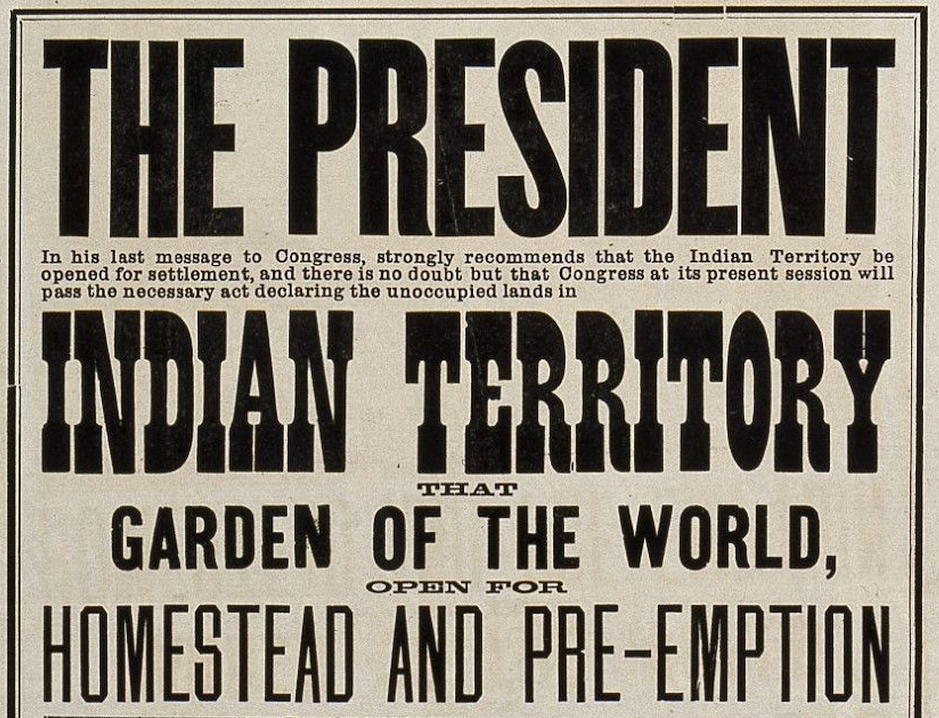

- Taking a hard look at the “raw materials of history”– primary sources

“The way to teach history is with primary sources,” Kristin said.

This makes sense, doesn’t it? Focus on primary sources and get students to discuss their perceptions and perspectives. It reminds me of how another teacher of mine taught religion class– never share your own opinion, only invite students to interrogate the information available.

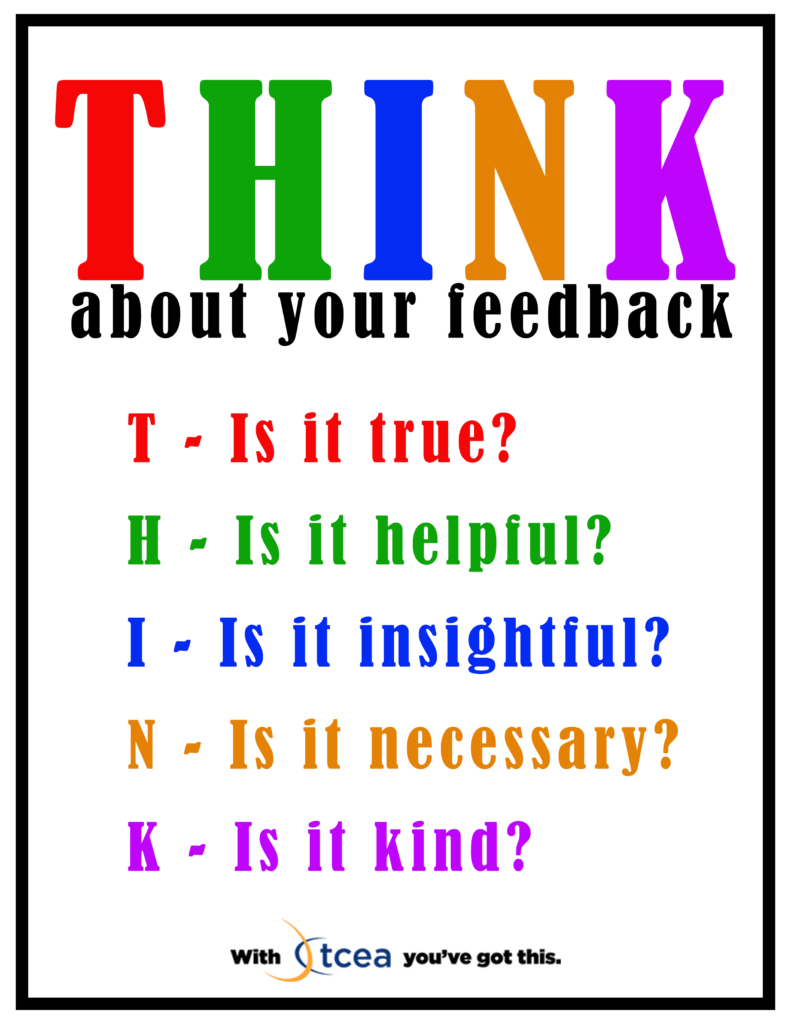

Primary sources are the raw materials of history. They are original documents, objects, and artifacts that were created during the period of time being studied. They differ from secondary sources. Secondary sources are accounts that retell, analyze, or interpret events. Usually, these appear after the events and period of history being studied. (Adapted from source)

Approaching History with Primary Sources

But what’s the best way of approaching the oceans of human history?

A challenge I imagine one might have is uncovering how to best teach history using primary sources. Textbooks align with the curriculum but primary sources present an unvarnished version of what happened. Students plug that into their brains, discuss with peers, then draw conclusions. There’s real value for educators in becoming curators of quality primary sources.

“The truth of the matter is education is political,” says Tinisha Shaw. She suggests that each teacher create curated lists of materials they’ve vetted, “primary sources and secondary sources that hit particular themes [to be] discuss[ed].”

Dr. James Loewen suggests (source as cited) questions to apply to secondary sources:

- When was the secondary source created?

- Who created it, included or omitted from the account? Are they treated as heroes or villains?

- Why was it created? What were their ideological needs and social purposes?

- What was/is the intended audience? How does the account change if it includes powerful people or institutions? What do other sources say?

- How could the story differ if a different group had told it? How is the story received? Forgotten or remembered? Accurate account or less than accurate?

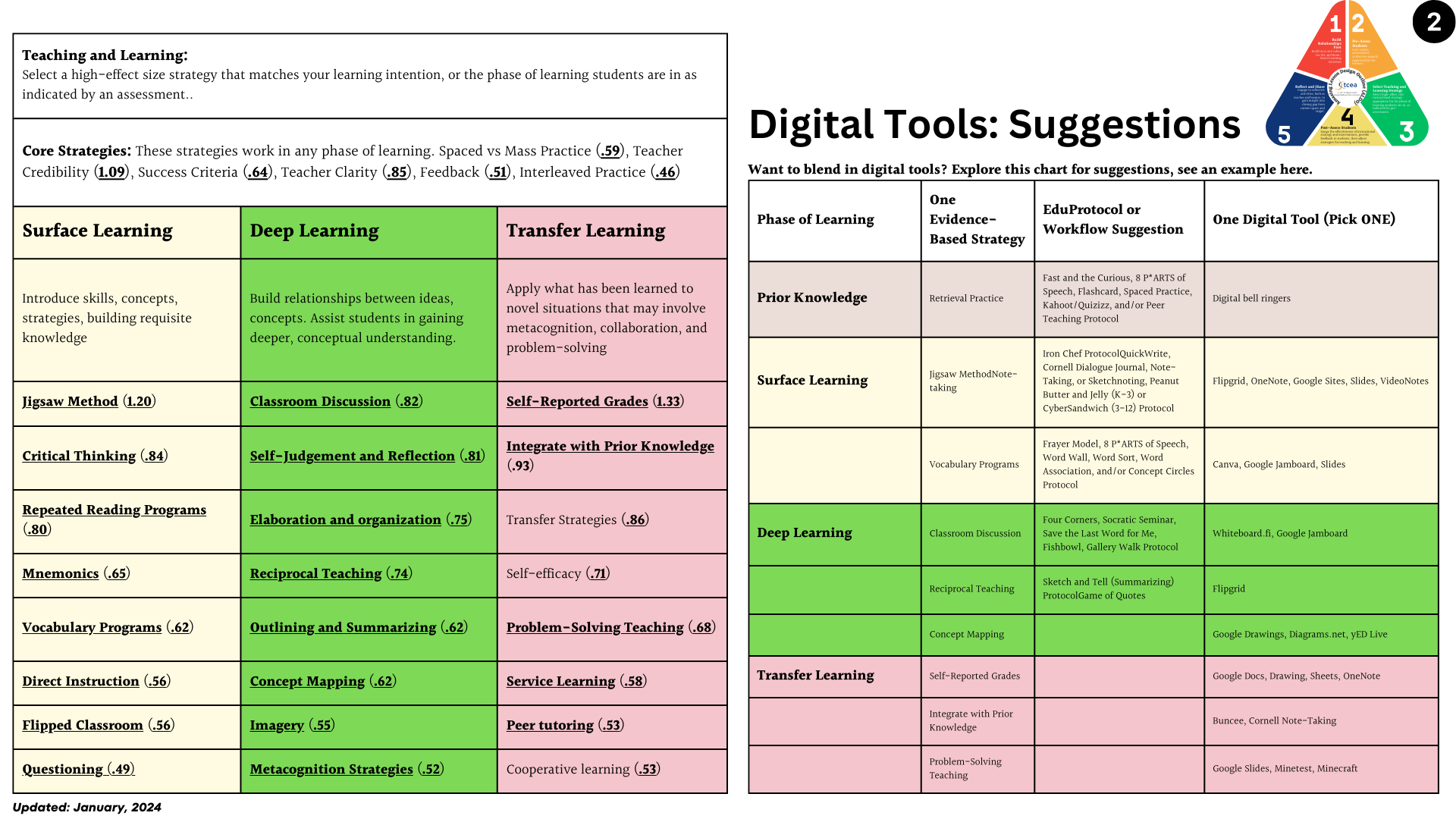

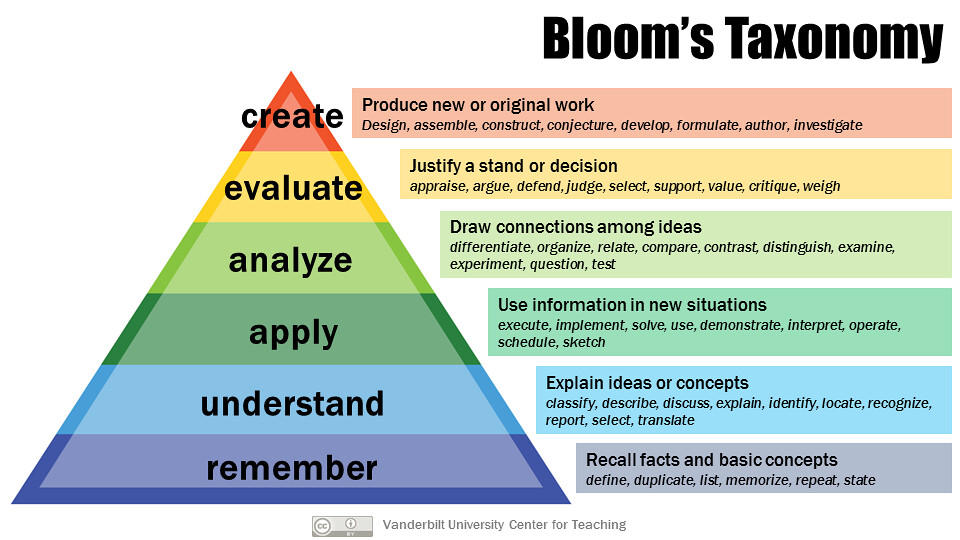

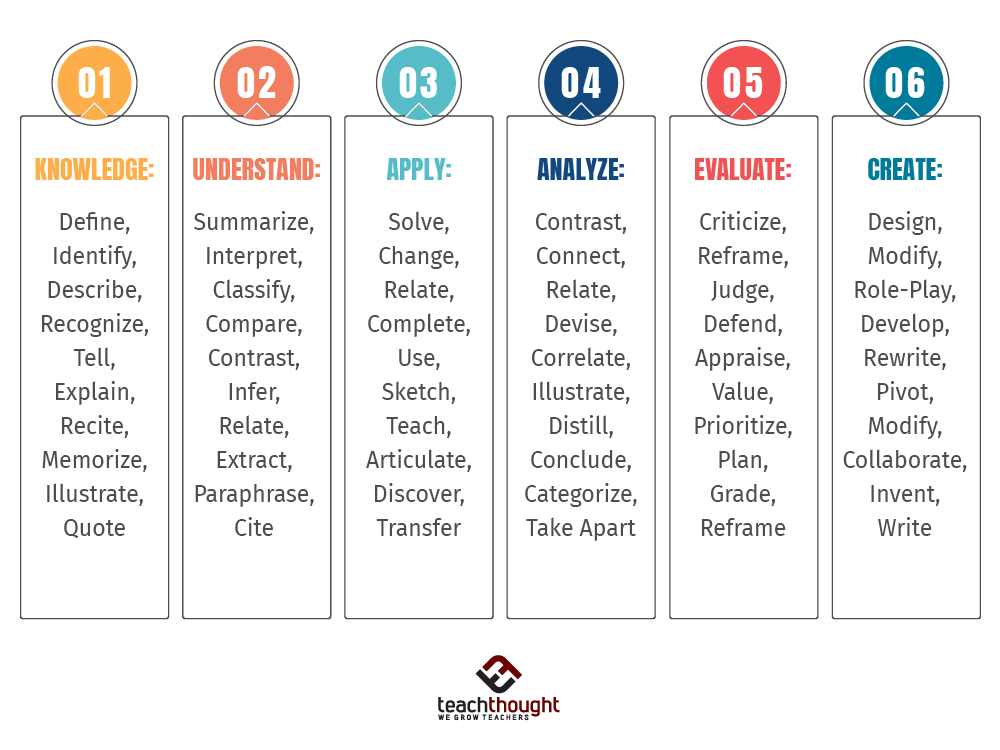

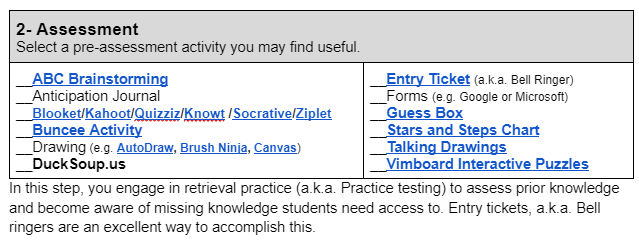

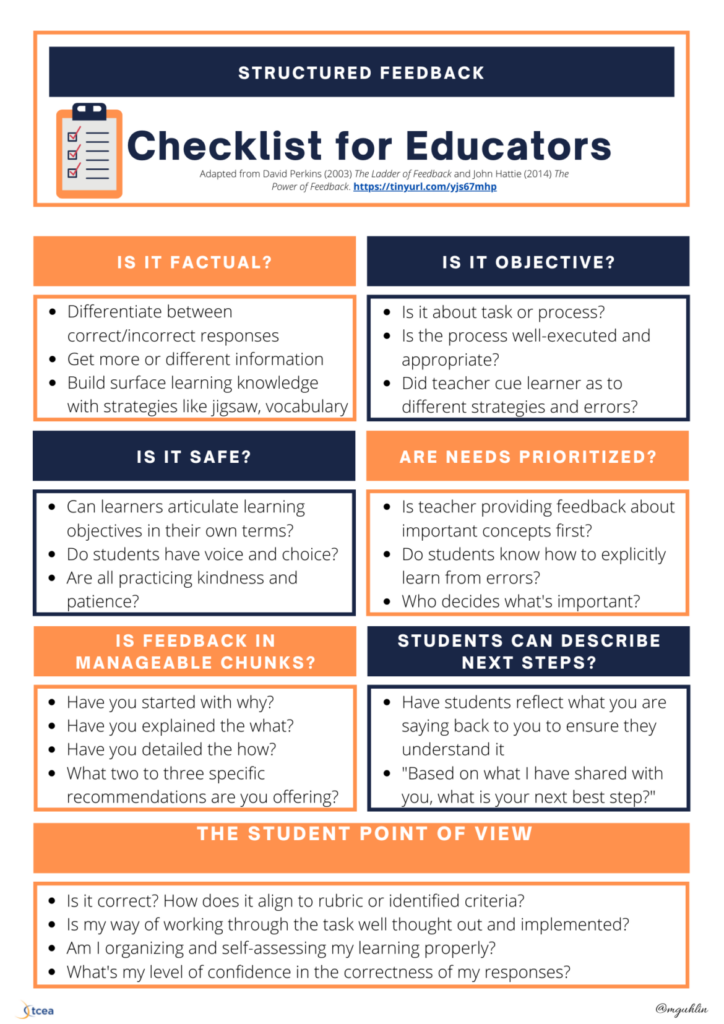

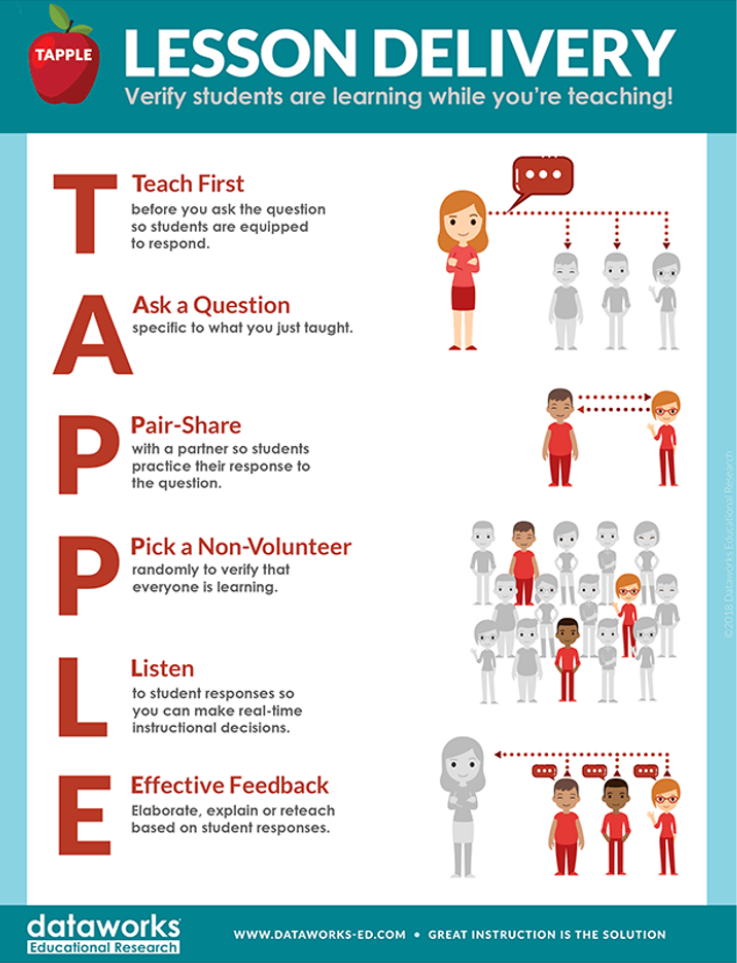

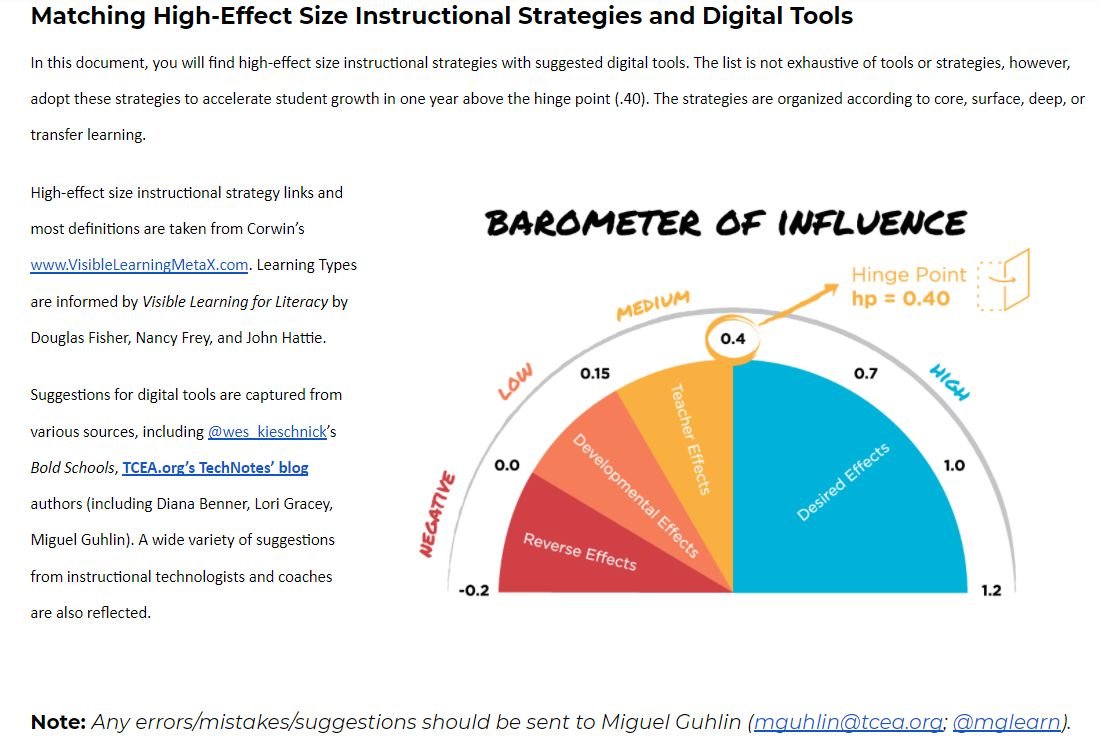

This is a lot of questions and perspectives to juggle. It’s the perfect situation to rely on two powerful high-effect strategies. Those include the Jigsaw Method in the context of a Problem-Solving Teaching lesson.

With all this in mind, the teacher’s role becomes one of “orchestrator.” The teacher organizes the sources and then has a process– a process that involves students comparing perspectives. Here are three approaches you can take to teaching with primary resources.

Image Source: Matt Doran, Historiography for the Secondary Social Studies Classroom

Approach #1: Historiography

This approach involves understanding changing interpretations of past events. In this case, students can follow a step-by-step guide to creating a historiography. Those steps may involve:

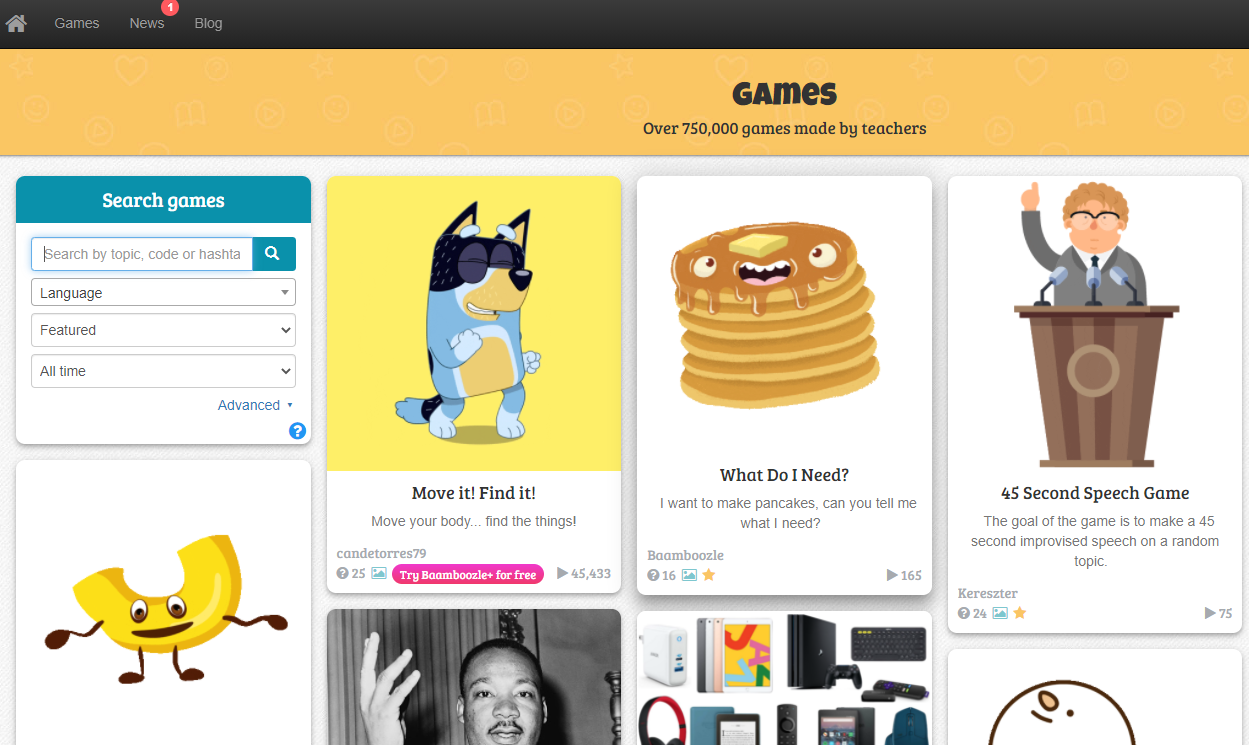

- Identifying a Topic. Students can create a concept map to explore past events and how others have interpreted them. You can use concept mapping tools like CMAP Tools that make it easy to embed links, and links can go directly to primary sources.

- Creating a bibliography. This can include book reviews, books, article anthologies, videos, and periodicals.

- Assessing Perspectives. Map out the perspectives presented. Be sensitive to how authors represent events and determine and identify bias.

- Crafting a historiography. Create a chronological timeline, tracing changes over time, and identifying perspectives. Make a note of each topic and how interpretations have changed over time. (Adapted from source.)

Approach #2: Four Question Method (4QM)

In the 4QM, students work to engage in four acts:

- Narration

- Interpretation

- Explanation

- Judgment

Each act comes with a question:

- Narration- What happened?

- Interpretation – What were they thinking?

- Explanation – Why then and there?

- Judgment – What do we think about that?

This approach enables students to process key information. Students make connections. They link what they are studying and their own thoughts on what’s happened. Explore the Four Question Method (4QM) online on the authors’ website.

Approach #3: Curating a Collection

Create and curate a collection of trusted primary courses with students. Know about the APART method (watch video)? It’s an approach that involves looking at:

A – Author

P – Prior knowledge

A – Audience

R – Reason/purpose

T – The message

Another approach you could choose to use is the OPVL technique (watch video) and the OPVL site:

O – Origin

P – Purpose

V – Value

L – Limitation

Where Can I Find Primary Sources?

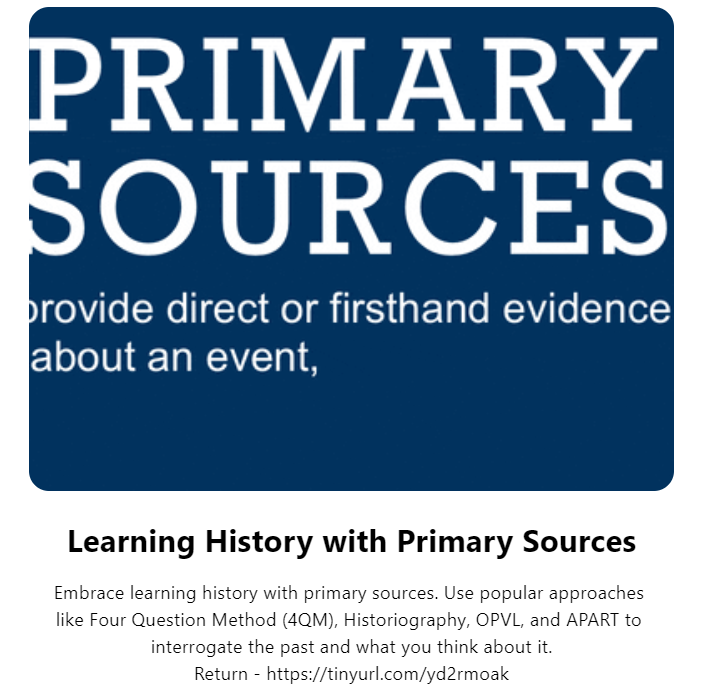

Now that you have some ways of analyzing historical documents, what primary sources are available? Ample resources exist for teaching with primary sources, and you can find a list in this Wakelet collection.

View Wakelet Collection – https://tinyurl.com/yd2rmoak

Teaching history with primary sources works. It works because it focuses on what happened, who did what, and why. And, more importantly, it challenges students to think in a critical manner about how interpretations of history have changed to fit the needs of the powerful. How have you used or will you use primary sources in your history class?

A Cry for Help: I Can’t Form an Online Community

A Cry for Help: I Can’t Form an Online Community