Discover tools, strategies, and resources for instructional coaching. Explore insights to support teachers and enhance professional learning.

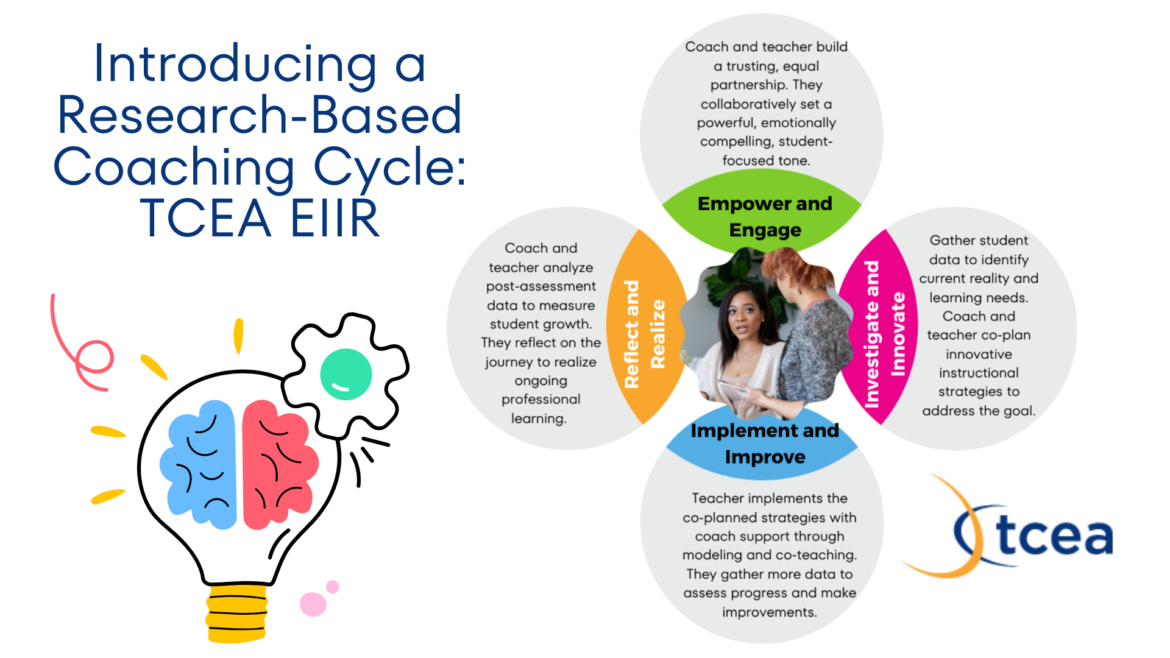

Boost Teacher Growth with the TCEA EIIR Coaching Cycle

Doing what we can to improve as educators remains a top priority. Our aim is to enhance student learning outcomes as we work on ourselves using research-proven instructional coaching methods. That’s where TCEA’s EIIR Coaching Cycle comes in. This cycle provides a structure that coaches and teachers can use to collaborate as they set meaningful, relevant goals. What’s more, it also relies on evidence-based strategies. Let’s explore the five phases of effective coaching and then get into the four stages of this coaching model.

Looking to level up your educational coaching skillset?

Fuel your passion for teacher development with TCEA’s Instructional Coach Certification! Dive into coaching cycles, tech tools, communication, and more with this carefully crafted course, designed specially for educational coaches like you.

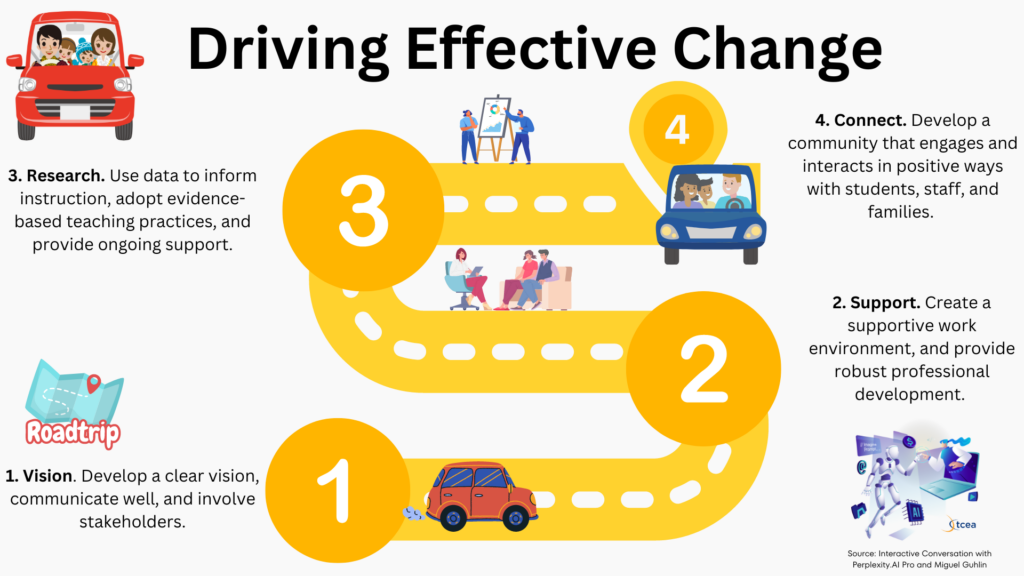

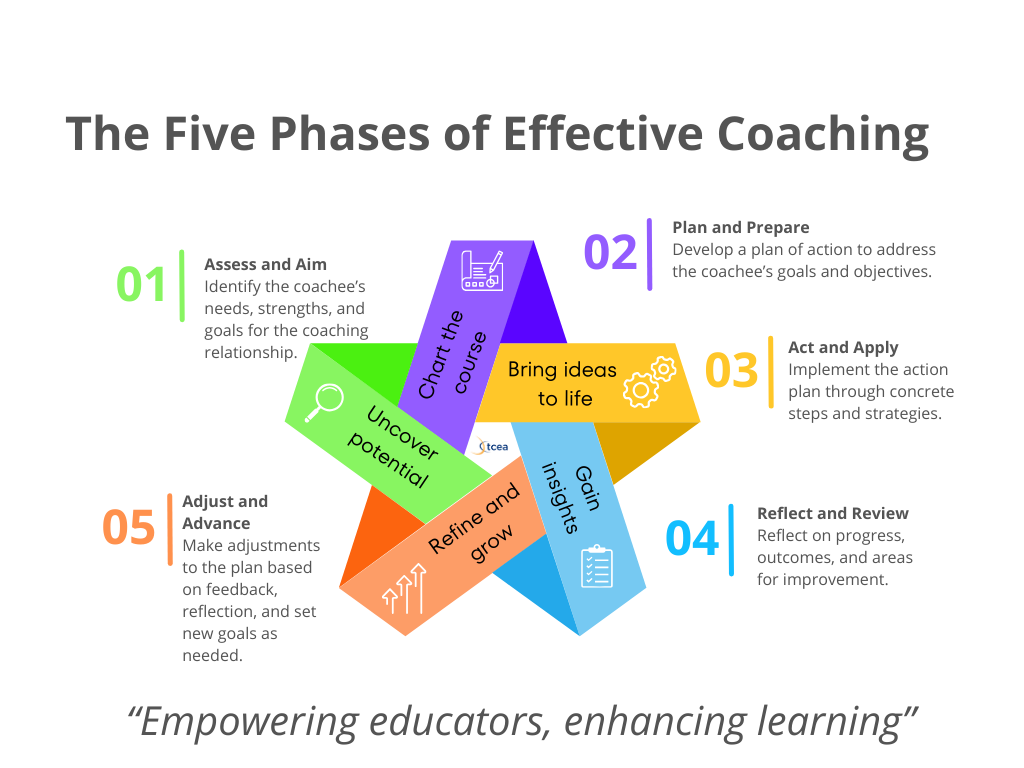

While many coaching models follow a traditional five-phase approach of Assessment and Goal Setting, Planning and Action, Implementation, Reflection and Evaluation, and Adjustment and Revision, TCEA offers an innovative four-stage cycle that streamlines these phases for maximum impact. The TCEA EIIR Coaching Cycle combines elements of these traditional phases into a more focused, research-based approach.

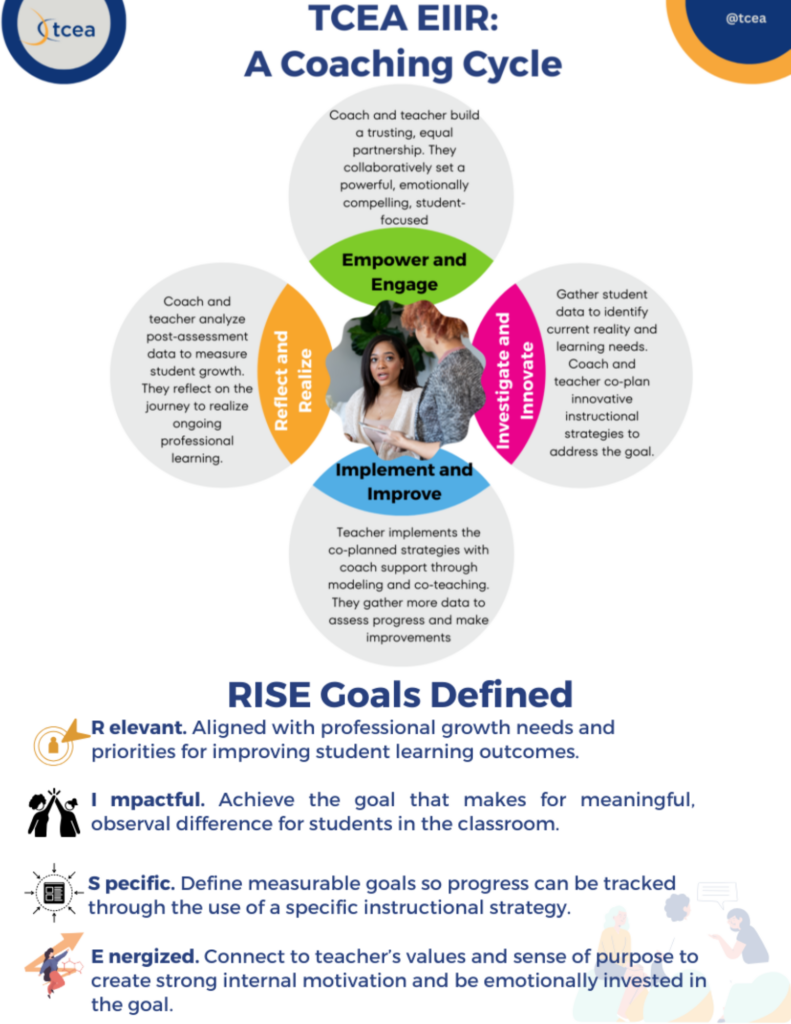

It begins with Empower and Engage, which encompasses assessment and goal setting. The Investigate and Innovate stage blends planning and initial implementation. Implement and Improve focuses on ongoing implementation and real-time adjustments. Finally, Reflect and Realize combines reflection, evaluation, and planning for future growth. This structure provides a comprehensive yet efficient framework for instructional coaching that aligns with established best practices while offering a fresh, targeted approach to educator development.

Digging Into the TCEA EIIR Coaching Cycle

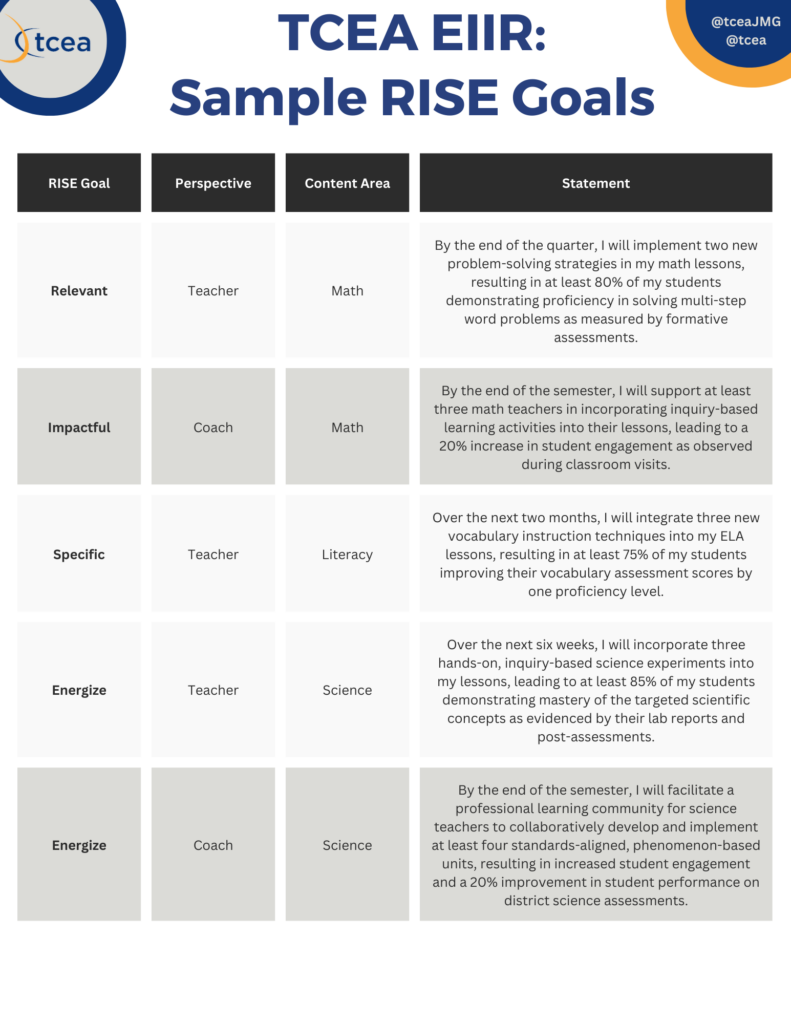

Let’s take a moment to dig into the EIIR Coaching Cycle and define each of the key elements of the RISE goal-setting framework.

1) Empower and Engage. In this stage, the coach and teacher build trust and partnership. They set a clear, meaningful student learning goal together. This goal should follow the RISE framework — it should be relevant, impactful, specific, and energized.

2) Investigate and Innovate. In this stage, the coach and teacher learn and plan. They look at student data to better understand students’ learning needs. Then they gather more data to see progress and make changes as needed.

3) Implement and Improve. At this stage, the teacher and coach are teaching and adjusting. The teacher tries out planned strategies with the coach’s support. They continue to gather more data, adjusting as needed.

4) Reflect and Realize. In this reflect and grow stage, the coach and teacher review student growth data. They reflect together on what worked, identifying areas for improvement. They use their insights to guide teacher’s ongoing professional growth and plan learning opportunities that are relevant to supporting that growth.

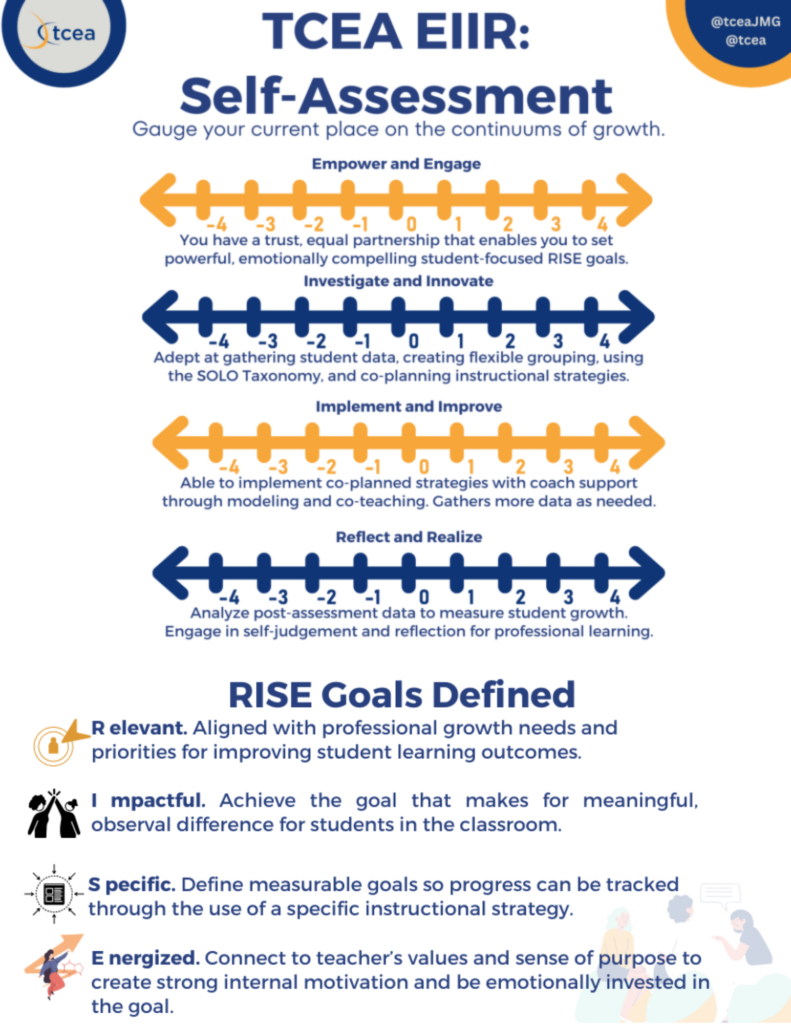

Self-Assessment

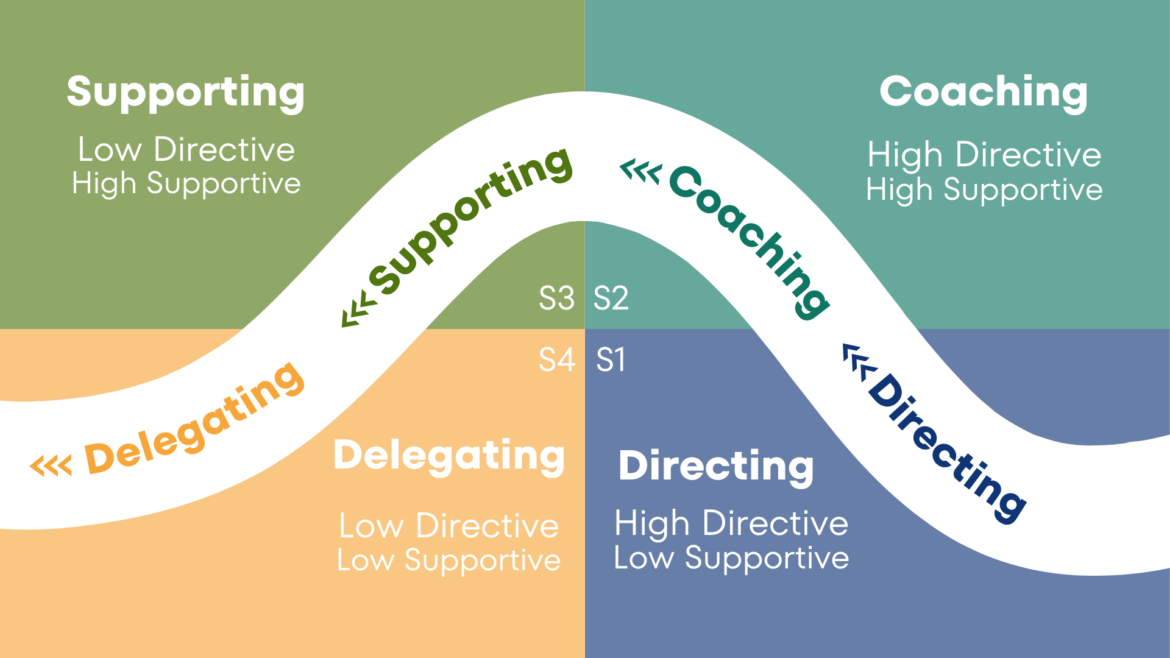

Since reflection is a key component of growth, use this self-assessment to ask yourself, “Where am I on the continuum for each of these stages? How open am I to receiving coaching feedback?” Then put a mark where you see yourself.

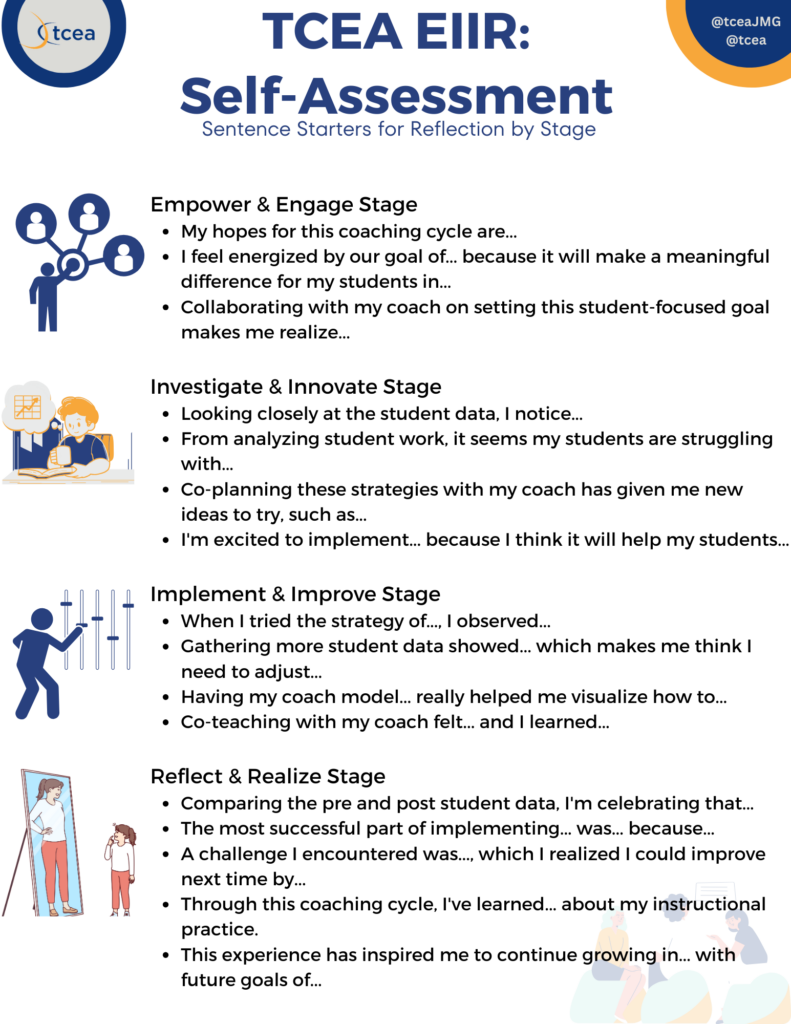

On the back side of the paper, consider the following sentence starters for each stage of the cycle.

Stage 1: Empower and Engage

Trust, mutual respect, and shared purpose are the foundations of a coaching relationship. It is critical that the coach and teacher build a collegial relationship. Together, they will develop a RISE goal:

- Relevant. The goal fits what the teachers needs to grow and help students learn. It captures the most important things the teacher needs to work on.

- Impactful. Achieving the goal leads to big changes in student learning that are measurable.

- Specific. The goal focuses on one thing and says exactly what to do so it is assessable.

- Energized. The goal connects to what the teachers cares about.

For example, a fourth grade science teacher and coach might set the following RISE goal.

“Over the next quarter, I will implement inquiry-based science activities in my lessons. This will result in at least 80% of my students demonstrating proficiency in scientific reasoning skills. I will measure this through the use of formative assessments.”

Let’s take a look at the next stage, Investigate and Innovate.

Stage 2: Investigate and Innovate

In this stage, the focus is on learning and planning. Both the teacher and coach analyze student data to better understand the current learning needs. They will examine student work and assessment data and make classroom observations as they work together to identify areas of growth.

Once they have done that, they make a plan to implement innovative instructional strategies. These could be strategies that engage in flexible grouping aligned to Surface, Deep, and/or Transfer Learning.

In the science example of scientific reasoning, the coach and teacher might co-plan. This co-planning would include a series of hands-on investigations aligned to state standards and blending in questioning techniques. They would plan to model scientific reasoning for students.

Stage 3: Implement and Improve

After co-planning, the teacher puts the plan to work with the coach present to offer support. This support comes in the form of classroom visits for modeling and co-teaching. It could also include real-time feedback.

This results in monitoring and adjusting. The science teacher and coach might analyze student work from the inquiry lessons. They would applaud any success, and target support for struggling students.

Explore these vignettes illustrating each stage of the cycle:

Stage 4: Reflect and Realize

In this final stage, both the coach and teacher measure the impact of their work. They do this by:

- Examining post-assessment data

- Reflecting on student growth in relation to the RISE goal

- Engaging in reflective dialogue to surface insights

- Identifying professional learning gains, and

- Pondering next steps

For example, the science teacher might celebrate that 85% of her students demonstrated proficiency. She would reflect on how the coaching process assisted her in facilitating student-driven scientific inquiry. She might decide to set a new goal, like integrating science notebooks as a tool to deepen student reasoning.

The TCEA EIIR Coaching Cycle

The goal of this tool is to assist coaches in better helping teachers. The RISE goal-setting framework focuses all efforts on being student-centered, and achievement oriented.

While this example focused on science, the model is equally applicable across grade levels and content areas. If you want to maximize instructional coaching efforts at your school, you can adopt the TCEA EIIR Coaching Cycle at no charge, or sign up now for TCEA’s Instructional Coaching Certification course to learn more. Upon enrollment, you’ll gain access to all the digital versions of the documents in this blog entry, as well as extensive instruction and support in improving your coaching process. What’s more, you get access to a free ebook on instructional coaching.