Explore the latest in educational research. Discover insights, studies, and strategies to inform effective teaching and learning practices.

Who loves reading? (raises hand) So you’re working with students to build their reading skills. That’s a big job! How are you working on building fluency? Let’s take a look at reading fluency and explore a few “not boring” ways to engage students in practice to build reading automatization and support comprehension.

What Is Reading Fluency?

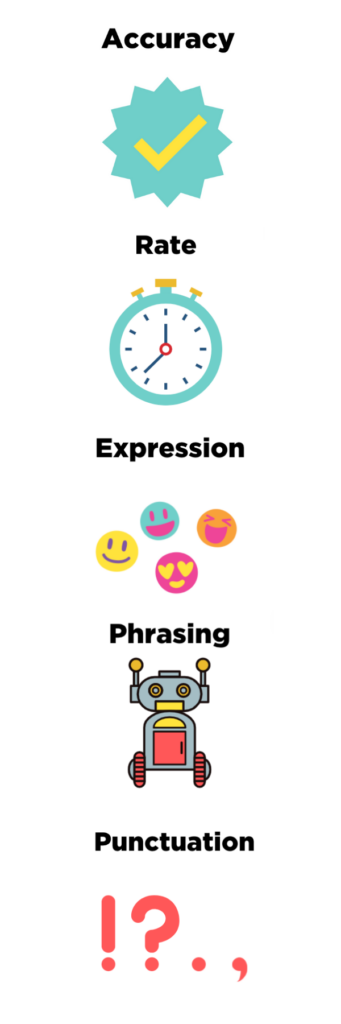

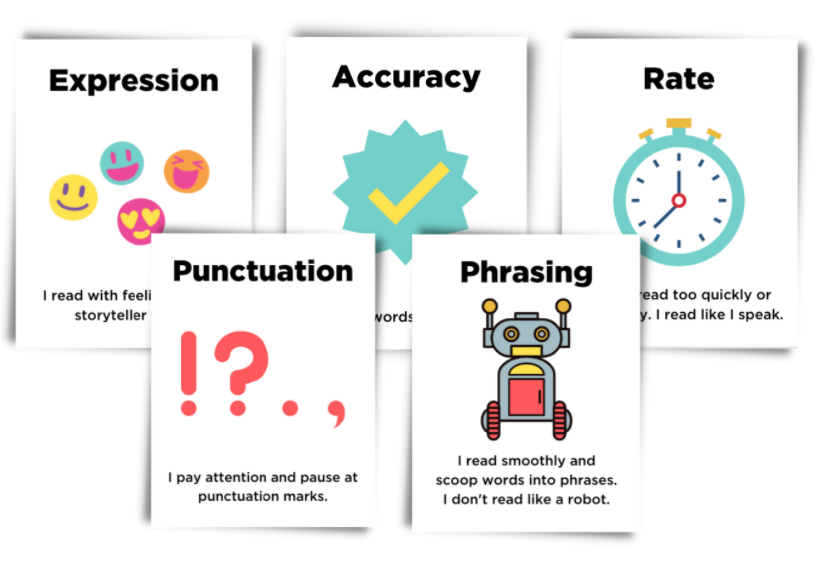

According to the International Literacy Association (and most definitions), reading fluency is made up of three measurable parts: accuracy, rate, and expression (or prosody). Some definitions also include phrasing as a component while others lump this under prosody. When a reader is considered fluent, they read at a nice pace, they accurately recognize words without noticeable effort, and they bring texts to life by making reading sound similar to natural spoken language.

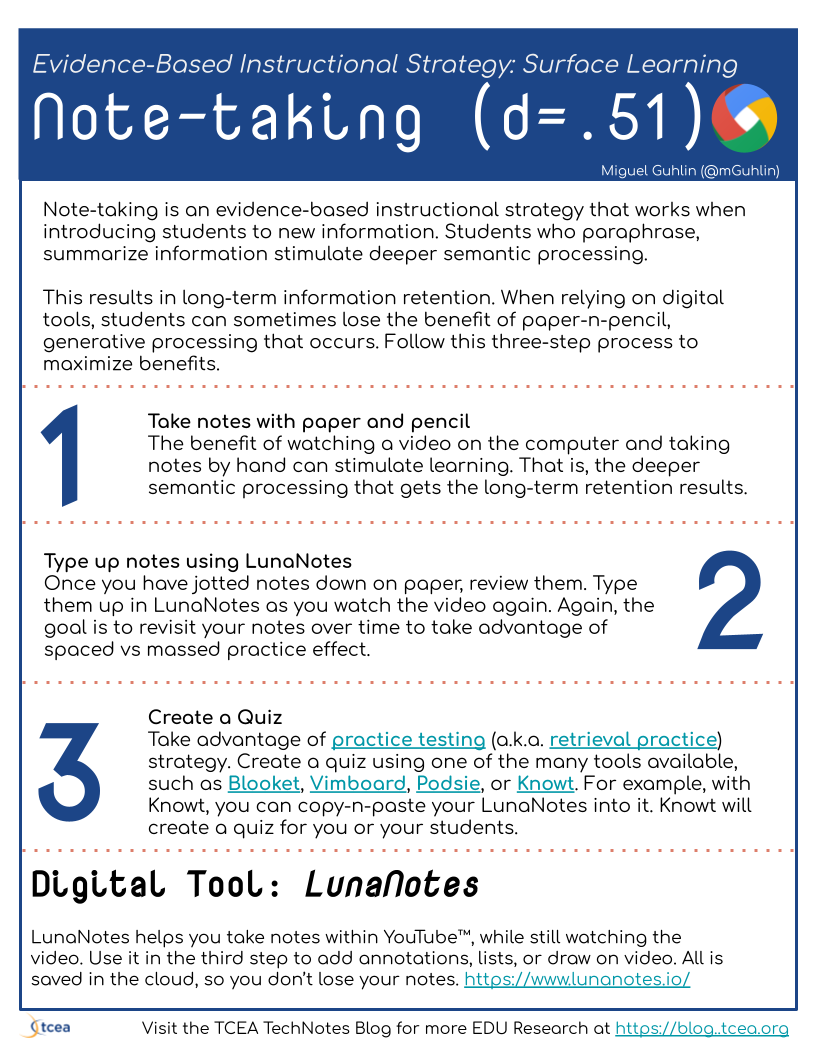

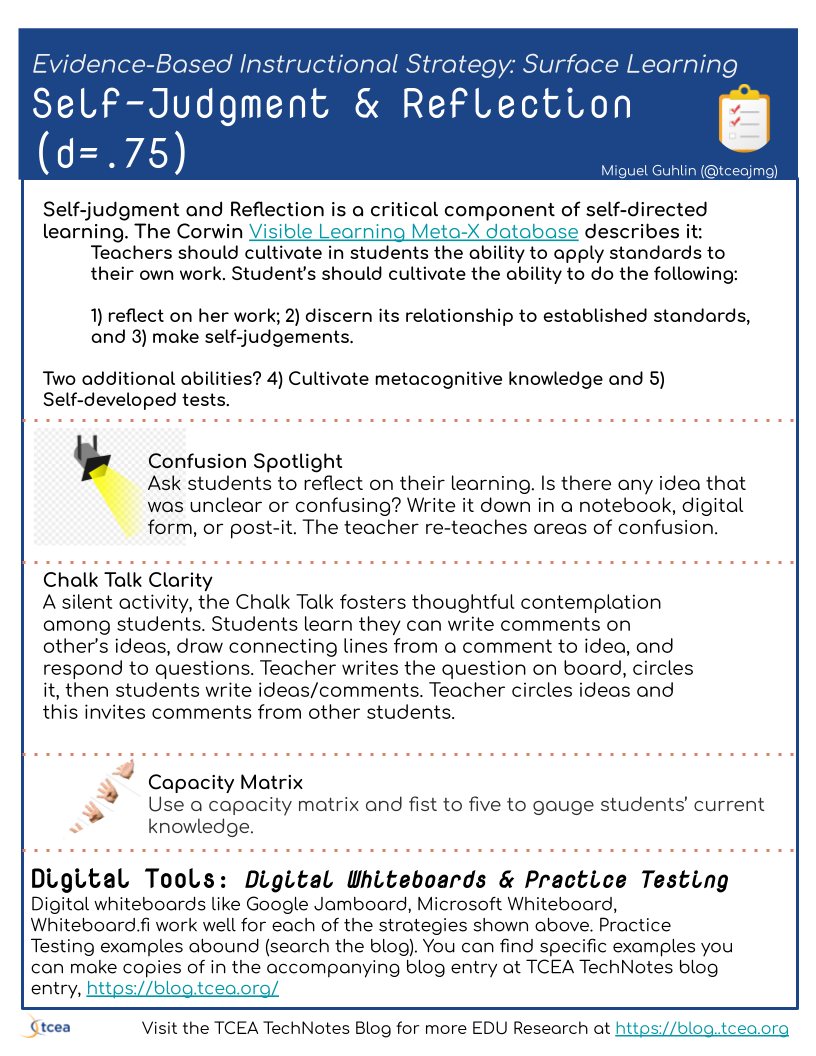

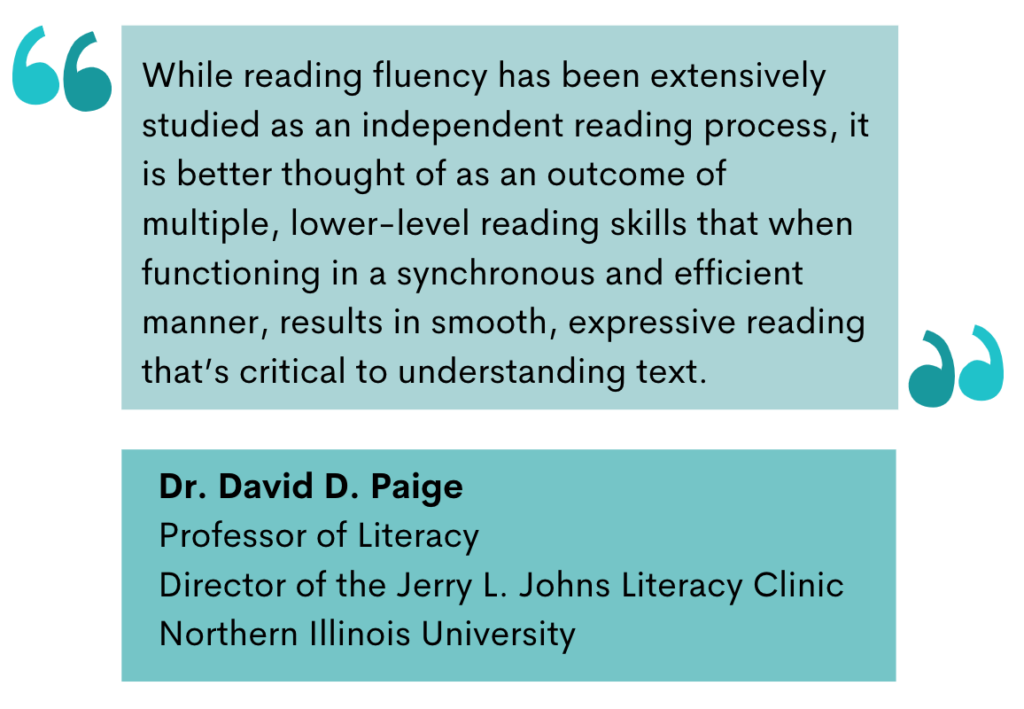

The ultimate goal is for reading to become automatic. And automaticity means that a lot of interdependent and interconnected skills and processes, like phonemic awareness, decoding, etc., must work together. For this reason, fluency is very complex. Don’t be fooled by the simple definition. I like what Dr. David D. Paige, Professor of Literacy and Director of the Jerry L. Johns Literacy Clinic at Northern Illinois University, says in his article “Reading Fluency: A Brief History, the Importance of Supporting Processes, and the Role of Assessment,”

Why Is Reading Fluency Important?

The Children’s Literacy Initiative (CLI) says:

You can sign up for a free CLI account to access a plethora of great fluency materials. Research definitely backs CLI’s statement. The more automatically a student reads, the more they are able to understand and interpret texts, and the more motivated they are to read. Imagine being a student that lacks fluency. Their brainpower is completely focused on decoding and deciphering the words to get through the text. This hinders them from devoting brainpower to interpreting meaning to understand what they read. Fluency is key to reading comprehension and reading enjoyment! And developing fluency skills, along with vocabulary acquisition, in the lower grades is vital to supporting reading comprehension moving forward.

Measuring Reading Fluency

Assessing students regularly and keeping running records will be key to monitoring growth and progress for making sure students are on track. Here are some tips from Reading A-Z on how to take a Running Record with an example mark-up. Let’s take a look at calculating components of fluency for assessment.

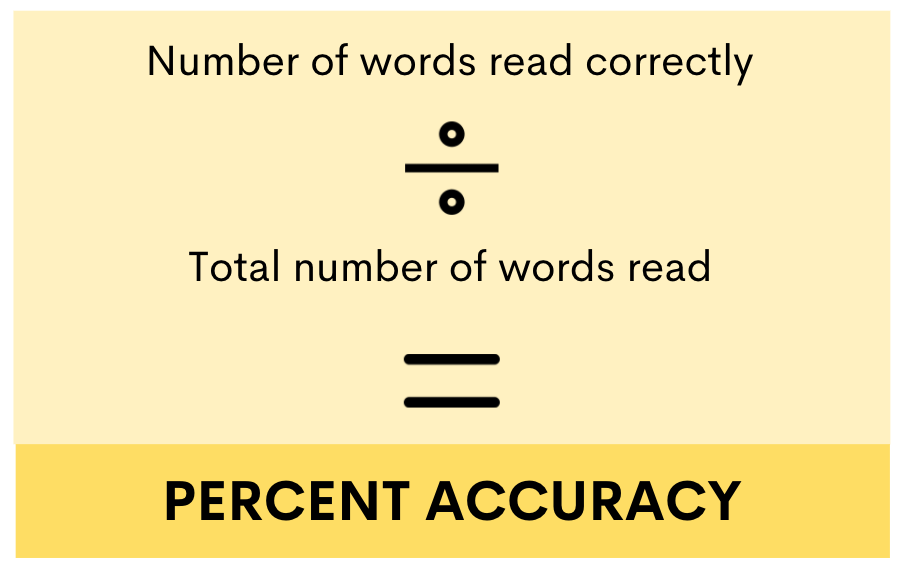

Accuracy

To measure accuracy, you can take the number of words a student reads correctly and divide it by the number of words read in total. For example, if a student reads a total of 100 words, and out of the 100, they read 90 words correctly, the student read the passage with 90% accuracy.

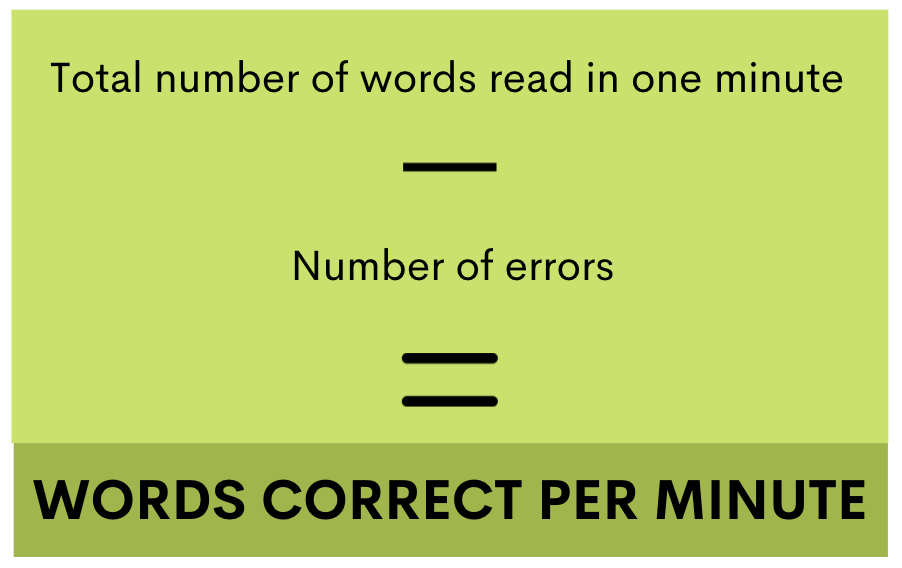

Rate

To calculate the rate at which a student reads, or the Words Correct Per Minute (WCPM), you will need to time them reading for one minute. Subtract the number of errors from the total number of words read, and you will have the WCPM. Let’s say a student read 95 words in one minute, and 80 words were read correctly. The student made 15 errors. You would take the 95 total words and subtract the 15 errors, so the student would read at a rate of 80 WCPM.

Prosody

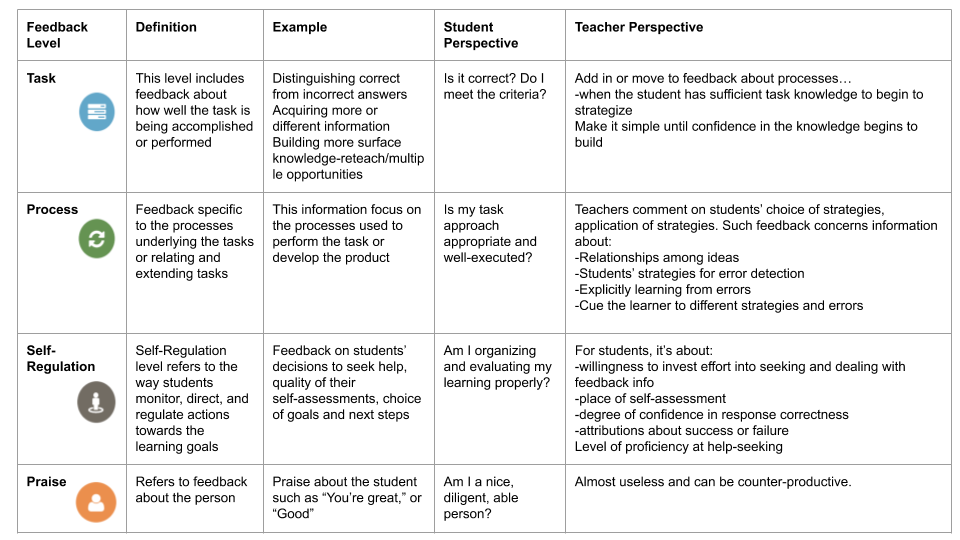

Prosody and expression are a bit more subjective; however, using a rubric can be very helpful. A rubric will guide in comparing students to a clear set of criteria. Here is a great rubric to help assess prosody from Dr. Tim Rasinksi of Kent State University.

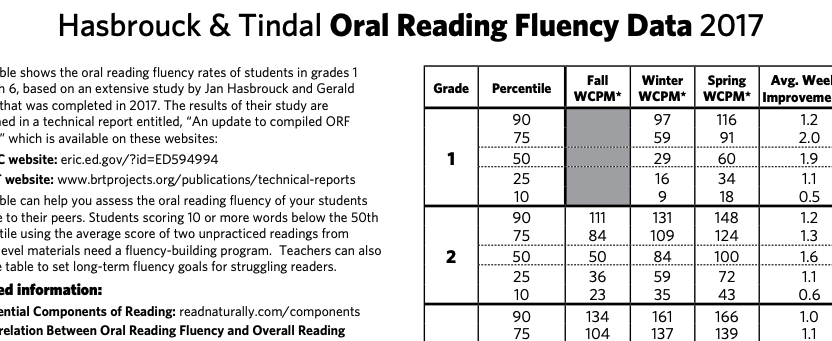

Fluency Norms

You’ve assessed your students’ fluency. Now what? In order to track growth and progress and to have discussions with parents about where students are at, it will be important to know how they compare to fluency norms or standards. Using a chart based on data collected on fluency levels at different grade levels is super useful. The Hasbrouck and Tindal Oral Reading Fluency chart (2017) tells you the percentiles and norms for WCPM for each trimester (fall, spring, winter) with the average rate of improvement by week. I’d recommend reading this report if you’re interested in the full research. Now, let’s get to some ways to improve fluency!

Ways to Improve Reading Fluency

1. Modeling

Reading aloud to students is one of the best ways to model reading fluency. It lets them hear what good fluency sounds like. Even in the upper elementary and middle school grades, reading aloud is an important part of building solid reading and listening skills. Take time to read to students and then place read aloud books in the classroom for students to access for re-reading. Having heard the story already, fluency can be built by revisiting the book or text to read it on their own. Not only that, but partner reading familiar texts can build motivation and fluency through modeling as well.

2. Fluency Centers

Fluency centers are a great way for students to practice and build fluency on their own or with a partner. Florida Center for Reading Research has some resources for fluency centers. Just choose your grade level in the menu on the left, and you’ll find a variety of resources to boost reading progress. We Are Teachers has an article with a whopping 37 ideas for literacy centers. You can create cards with Free Sight Words Flashcard Creator (Dolch, Fry, custom, and blank). And you can use these free PDFs to copy/paste Fry fluency phrases to create your own fluency phrase cards with this tool. You can also offer choice boards so students can choose how they’d like to practice at the center. Here are some example choice boards with some sample fluency activities. Feel free to download and edit the template.

3. Repeated Readings

Repeated reading is when a student reads a text multiple times until they no longer have errors. Students feel better and better as they see their fluency is improving each time they read the text. Here are some free repeated reading task cards to make repeated reading fun (and a little silly!). Key components to repeated readings are error correction, peer-to-peer feedback, and goal setting. Students can practice repeated readings independently or with a partner. This article by ThoughtCo has some great suggestions for choosing texts for repeated readings and how to use audio recording and timing in independent repeated reading. Additionally, the article presents choral reading, echo reading, and dyad reading as good partner reading activities.

4. Visuals References

Having visuals for students to reference is fantastic. Here are some fluency posters that you can give to students or hang in your classroom to help them remember what fluent readers do.

And here is a coordinating bookmark you can offer your students.

I hope you were able to get some ideas from this article. How do you work with students to build reading fluency? Please share your ideas and activities below to get the conversation going.