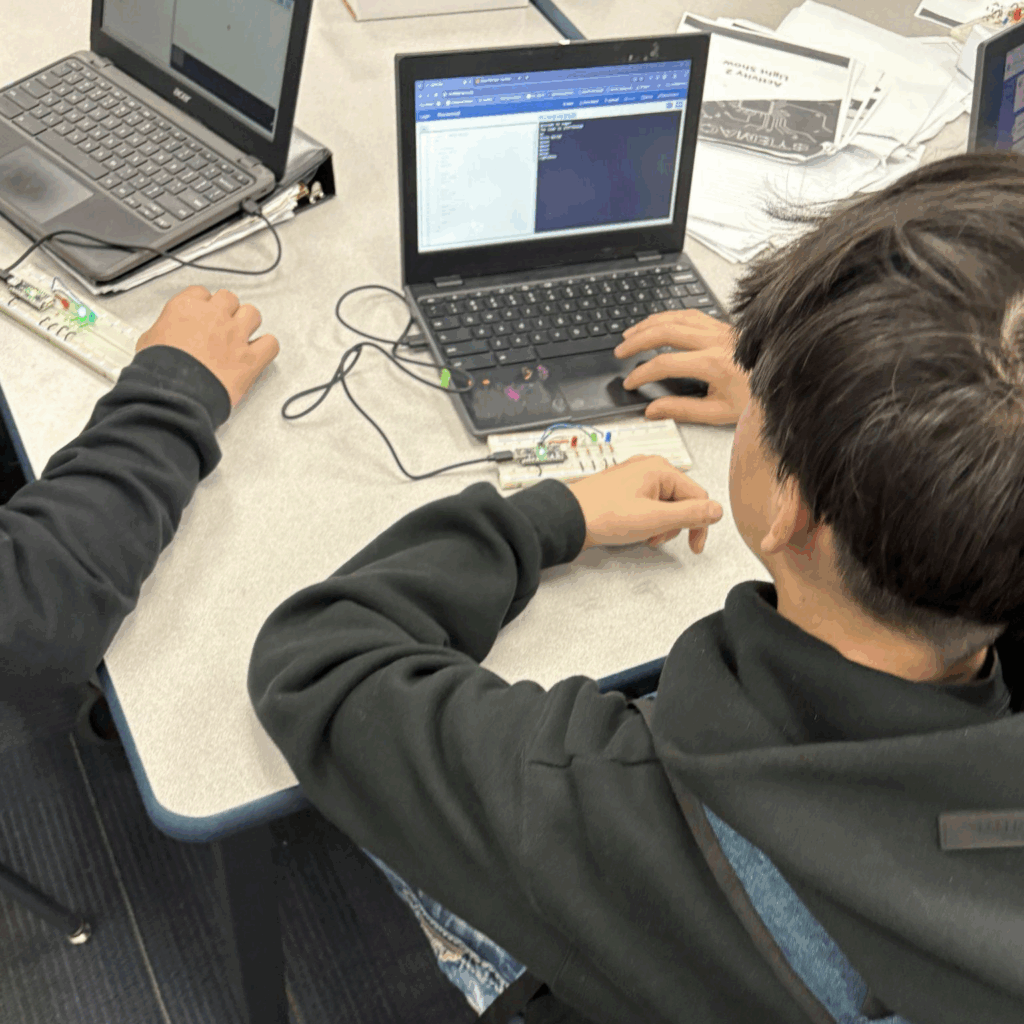

Imagine for a moment you are an 8th grade science student in a rural town in Texas. You are sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with two other students working on the same project as you are, and you’re working independently before you get together after to share your work. Each of you has your own kit, including a few different components for the tool that you are creating that your teacher has handed out. You have a breadboard with an Arduino, four clear LEDs, four 330-ohm resistors, four wires with the ends stripped off of them, a light sensor, and a USB cable. You’ve connected to your board via the USB cable and Arduino, and now your work begins.

Students at Round Valley Middle School in California using the STEMACES Web App and BasicBoard.

Your job is to build a night light that gets brighter as the room gets darker. You already know, from a previous activity, that an LED can be programmed to turn on when the light sensor gives a specific number. The average light reading that the sensor sends to the Web App via the Arduino is approximately 750 lux. But you’ve noticed that the readings are different when the light sensor sits flat on the table versus when it is held in the air. You make a note to make sure that the sensor is stable and doesn’t move too much so that you are more likely to have your light function as you intend it each time you use it.

You get the minimum criteria of the challenge taken care of, but there’s something nagging at you–the values you’ve assigned to turn the LED off (when the sensor detects a certain amount of light) are all the same number. You immediately start refining your code and adjusting the numbers to be different from each other, while still reflecting varying light levels in the room, so that the LEDs on your board will turn on and off, responding to levels of light, as smoothly as you wanted it to. Sitting back, you begin to think about other ways to improve your code–but notice your neighbor is struggling to get his LED to light up. You offer to look at his code, and all looks right as far as you can tell. Looking at his board, though, you notice that the LED is situated backwards compared to yours. You suggest flipping the LED, and as soon as he does this the light turns on!

There is time for a quick high-five, and a moment to celebrate, before your neighbor resumes

refining his code and you return to your own task.

The STEMACES Program

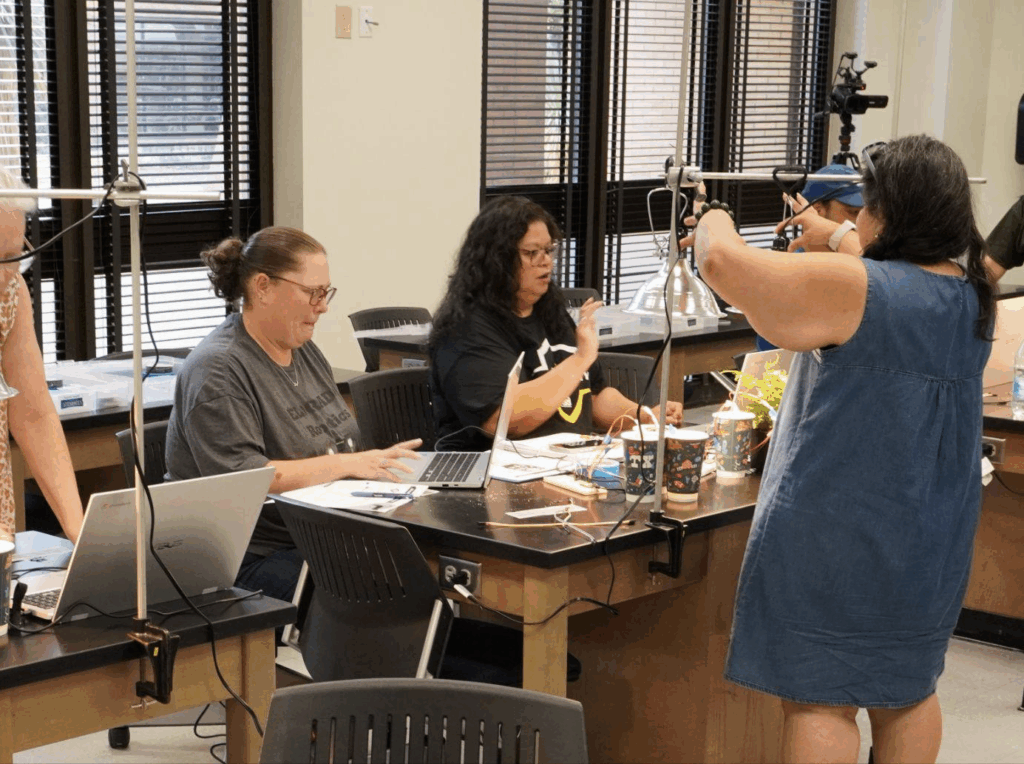

I attended the STEM And Computing Education Support (STEMACES) summer Professional Learning event at Angelo State University in San Angelo, TX, in July of this year. The Summer Institute was a week-long professional learning event that onboarded the 8th grade science teachers from Texas who are participating in the STEMACES program and gave them all of the science background, tools, and techniques they would need to lead the activities in their classrooms when the school year began.

8th grade science teachers in San Angelo, Texas, engage in an activity during the STEMACES Summer Institute in July 2025.

The teachers also learned about how they could connect the activities to the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS, standards. I was sitting next to a colleague of mine from California and a teacher from Texas. Just as the students in the short story at the beginning of this piece engaged with the code in different ways, we all approached the activity in our own way. I am a Communications person, with a Masters in English Literature, so the science learning taking place for me was genuine and new.

Part of what excites me most about working on the STEMACES team is the story of it. We know that learning comes more naturally and is more effective when a student is deeply engaged in what they are learning. We also know that for a student to be engaged, simply handing them a book and an instruction to “read” is very often not enough. What if, instead, we hand them a breadboard, some sensors, a few LEDs, wires, and resistors and tell them to build a night light? A night light is something students will likely have interacted with at some point in their lives. Being tasked with building one leads the student to ask themselves, “How does a night light work?” Moreover, they pursue the answer to their question with more engagement because they are an active participant in their learning.

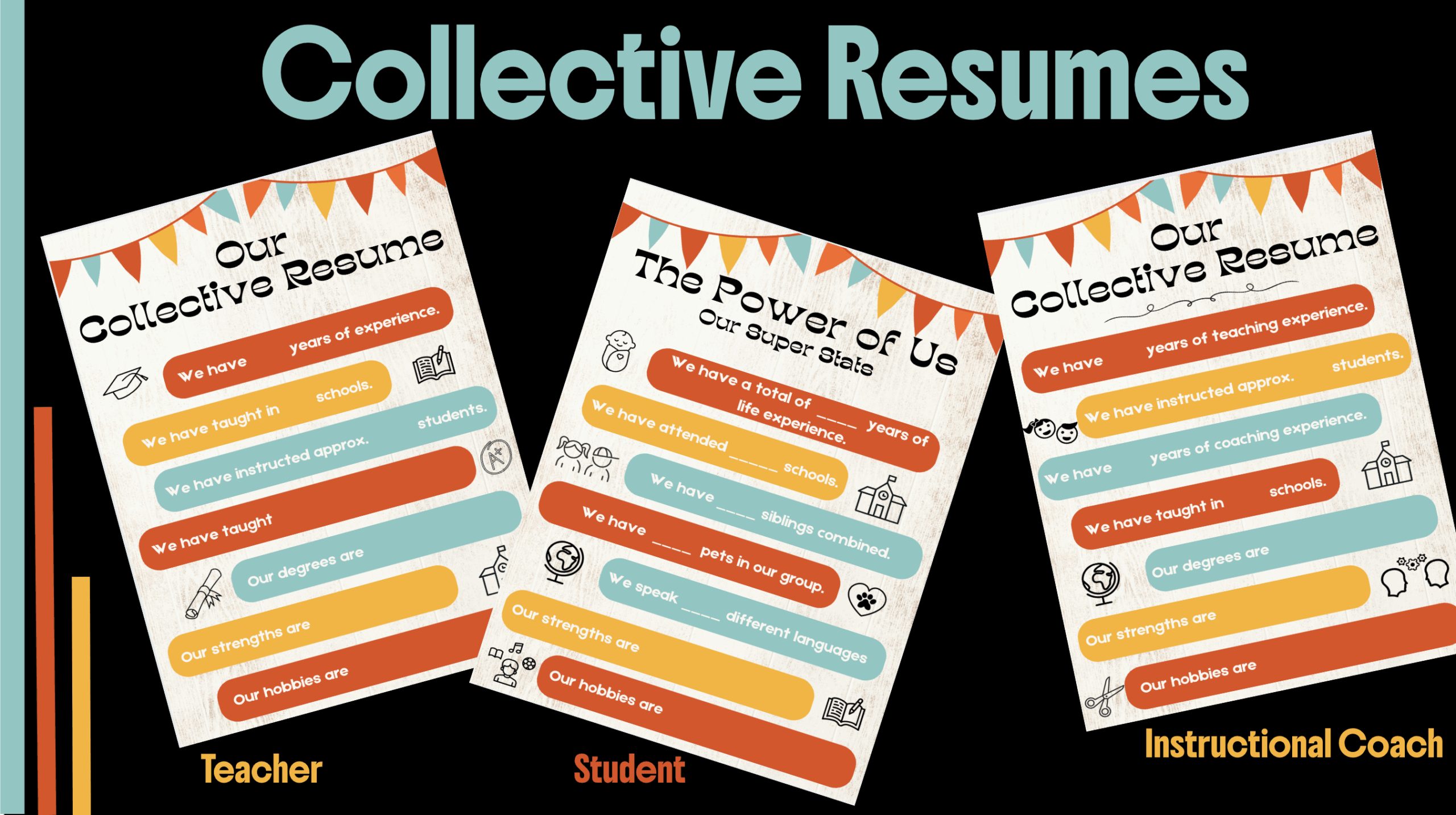

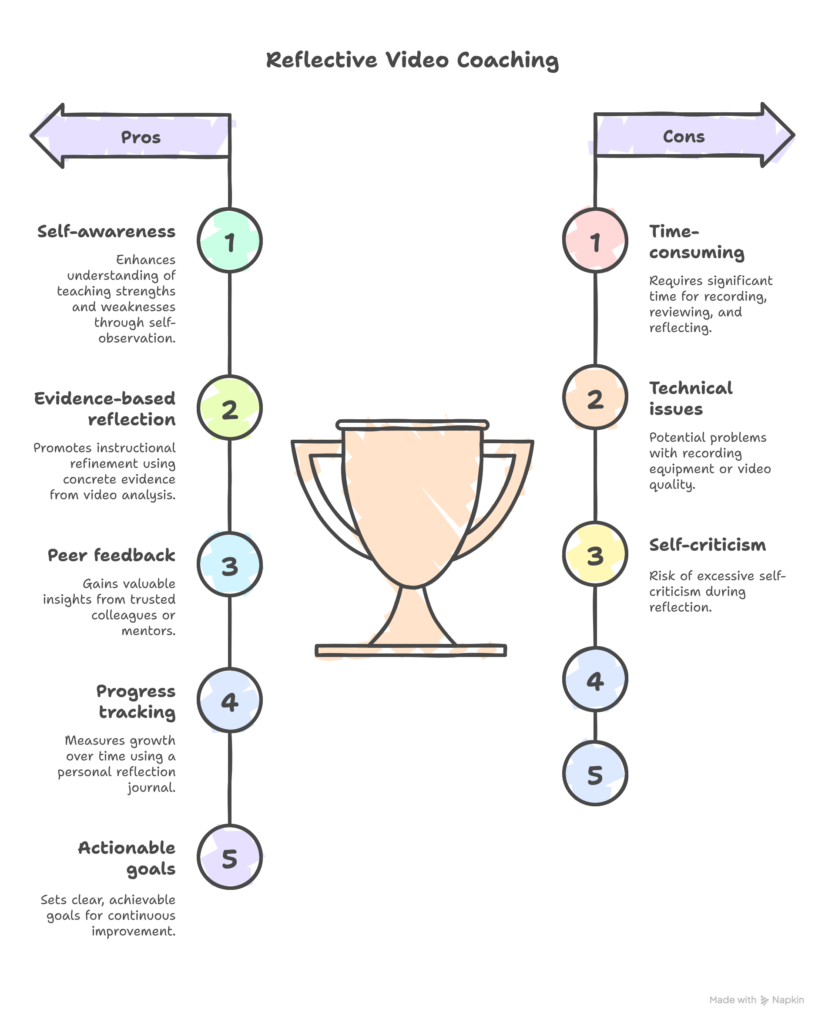

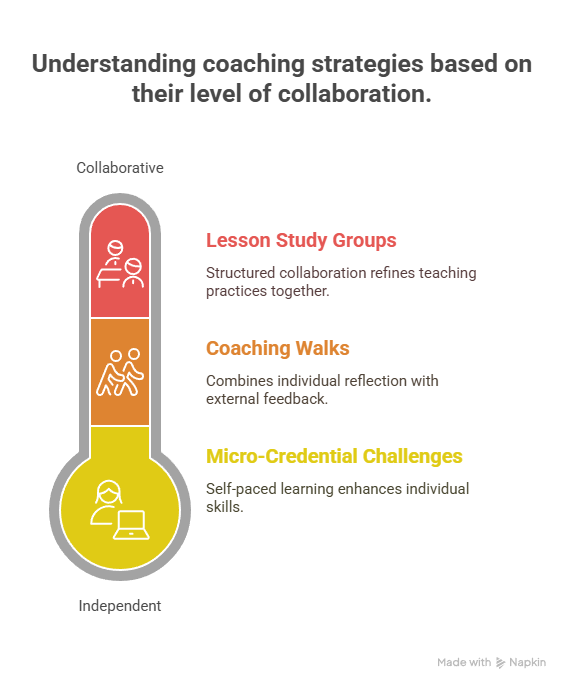

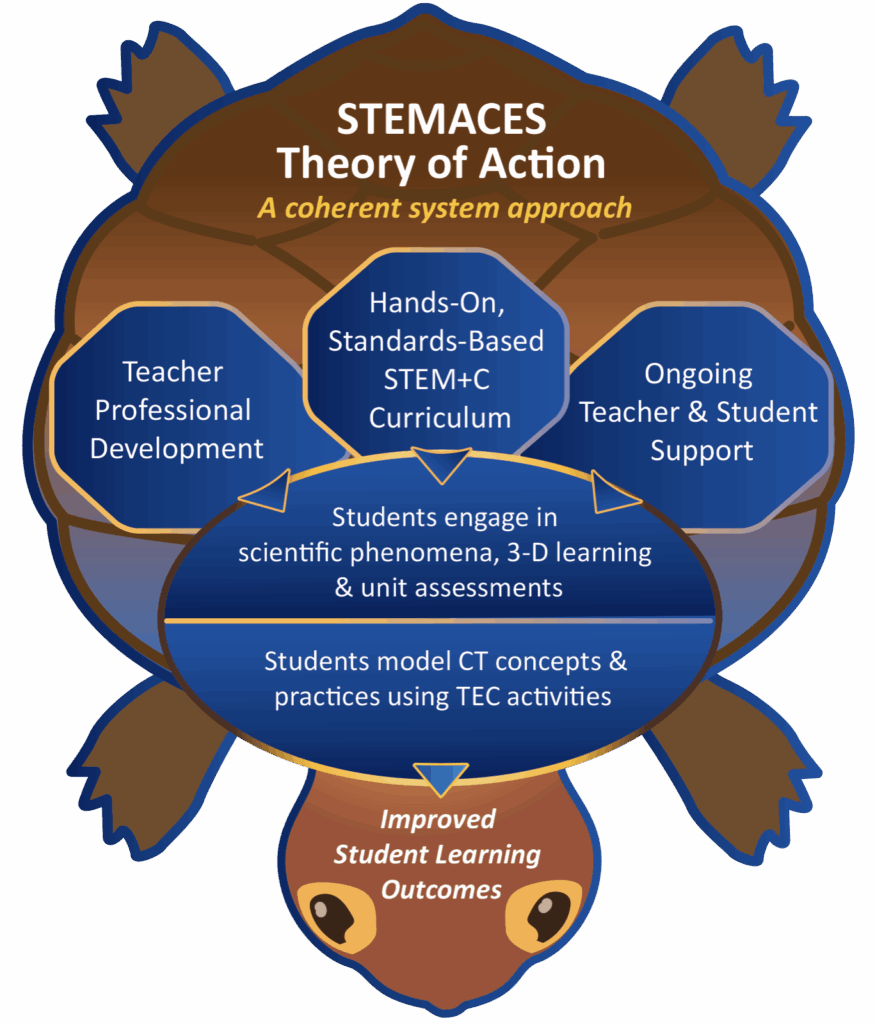

The STEMACES Theory of Action, also referred to as our “model.” The model prioritizes teacher professional development, hands-on and standards-based STEM+C curriculum, and ongoing teacher support.

The STEMACES Project was funded by the U.S. Department of Education to deliver this kind of learning to 8th grade students in rural communities. Our work on increasing science learning in the classroom through the use of hands-on, standards-based, curriculum with the hardware components (breadboard, Arduino, LEDs, sensors, etc.) began in 2013 with the funding of the Learning by Making (LbyM) project by the same federal EIR program that funded STEMACES.

In a quasi-experimental study done by WestEd demonstrated that bringing Logo coding, breadboards, electronics, and sensors into high school science classrooms improved grades in science by a whole letter grade and math by a half-letter grade (Li 2018). In 2023, STEMACES Project Director Dr. Laura Peticolas secured the mid-phase grant from the Department of Education to scale our work with 9th grade students in California to 8th grade students in California and Texas. At the heart of the STEMACES program are three priorities: Prioritizing teacher professional learning, providing hands-on, standards-based, STEM+C curriculum, and the upkeep of ongoing teacher and student support. We believe that if we can show that our model works in both California and Texas schools, it has the potential to make meaningful change in science education happen for students and teachers across the United States.

LbyM, and now, STEMACES, are both made possible by a unique custom-built software that we call the Web App. This platform is useful to middle school students and teachers because our team designed it to read and write to external devices (like the Arduino on our BasicBoards) from a web browser–something not possible before the creation of the Chrome Web Serial API in 2020. This allows students to focus on algorithmic thinking while coding with hardware instead of needing to learn about compiling, header files, and complex syntax. We have worked for years on this platform, making sure that it is as stable and easy to use as possible, which makes it a very powerful tool for teaching science and computing to students. Moreover, our team believes it is a powerful tool to support computational thinking–something that there was not even an assessment for, before our partner organization, WestEd, began developing it.

The LbyM Technology Platform: The browser-based Web App and the BasicBoard (a breadboard with Arduino, LEDs, and resistors).

We are now recruiting science teachers in Texas to participate in a study being put on by WestEd (very similar to the study that previously showed LbyM improved grades in science and math in 2018). If this program sounds like something that your students could benefit from, we would be thrilled to work with you.

Please visit our website at stemaces.sonoma.edu/join to sign up or request more information.