As we all know here in Texas, every grade level will have an “extended constructed response” on the STAAR test this school year. This response will either be informational or argumentative and will be an “essay.” Let’s take a look at exemplars and rubrics before we dive into an argumentative/opinion writing strategy for the elementary grades.

STAAR Test Example Responses

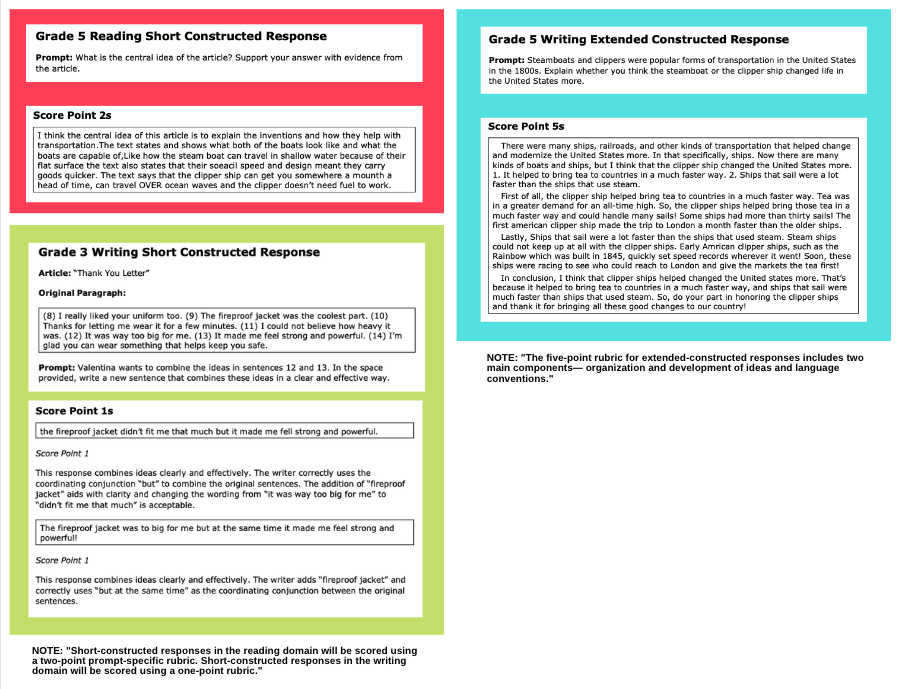

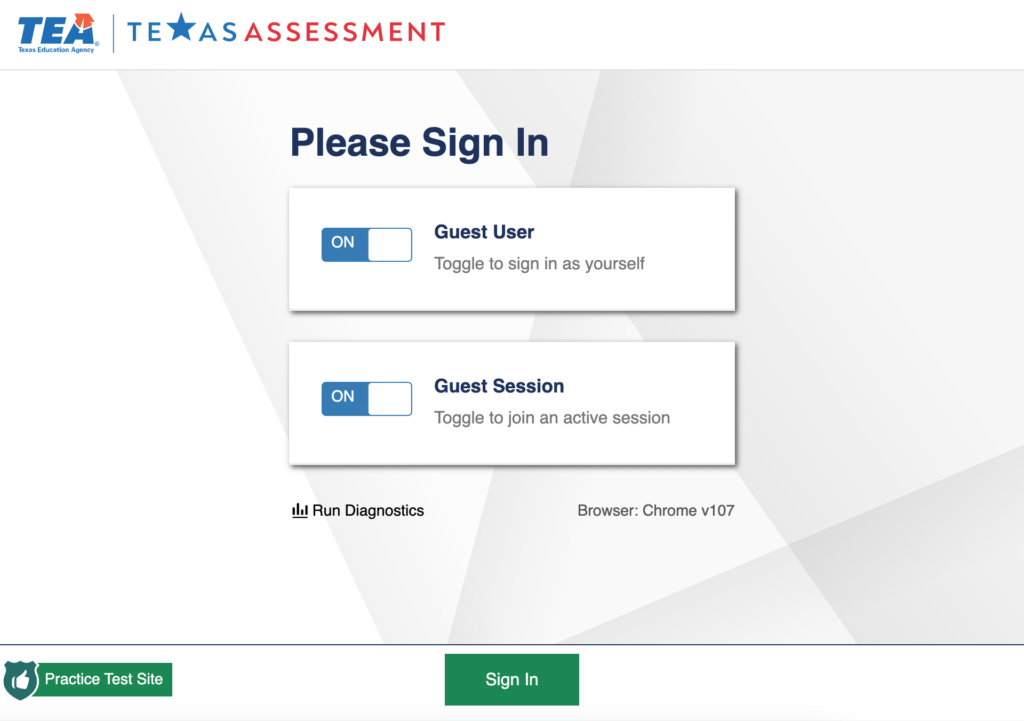

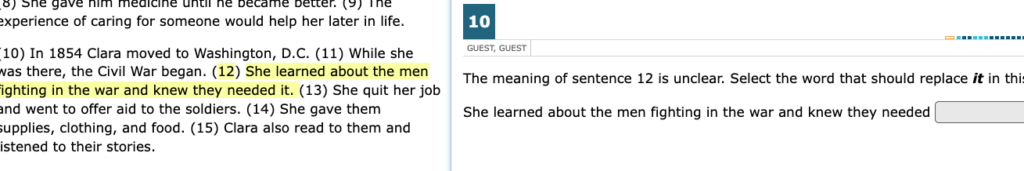

Here are some exemplars for grades 3 and 5 (for both short and extended constructed responses) provided by TEA (Texas Education Agency). These prompts and exemplars come from the field test, and this document walks you through the scoring. I go over more information about the constructed responses, STAAR test tools, and provide a few resources in Reading Language Arts STAAR Test Resources.

STAAR Argumentative Writing Rubrics

- RLA Grades 3-5 Argumentative/Opinion Writing Rubric (10/18/22)

- RLA Grades 3-5 Argumentative/Opinion Writing Rubric-Spanish (10/18/22)

- RLA Grades 3-5 Informational Writing Rubric (10/18/22)

- RLA Grades 3-5 Informational Writing Rubric-Spanish (10/18/22)

What’s the Difference Between Short and Extended Constructive Responses?

Here are exemplars from the stand-alone field test. The 5th grade prompts and responses are for the same passage, “Steam and Sail”. The responses on the left are short constructed responses (SCR), and the one on the right is an extended constructive response (ECR). The grade 3 response is within the writing domain, not the reading domain. There are no exemplars for grades 3 and 4 to reference for ECR in the scoring guide.

How to Teach Argumentative/Opinion Writing

So, of course, there are lots of ways to teach opinion writing to elementary students. But I’m a huge fan of the Gradual Release of Responsibility (GRR), and I’m also a huge fan of discussion and verbal practice before beginning the writing process. That said, I’m going to walk through using GRR with some resources for teaching opinion/argumentative writing at the elementary level. This strategy is adaptable and meant to be built on over time, so the example given isn’t necessarily 5th grade, score point 5 level, but it can get students there with practice and some adapting!

Review: Fact vs. Opinion

Whether you’re teaching first grade or fifth grade, it’s always good to start with a review of the difference between fact and opinion. Here are a few resources for this.

- Florida Center for Reading Research Fact or Opinion Game

- Factile Fact vs. Opinion Game

- Teaching with a Mountain View: Four Activities to Teach Fact vs. Opinion in Upper Elementary

Talk Before You Write!

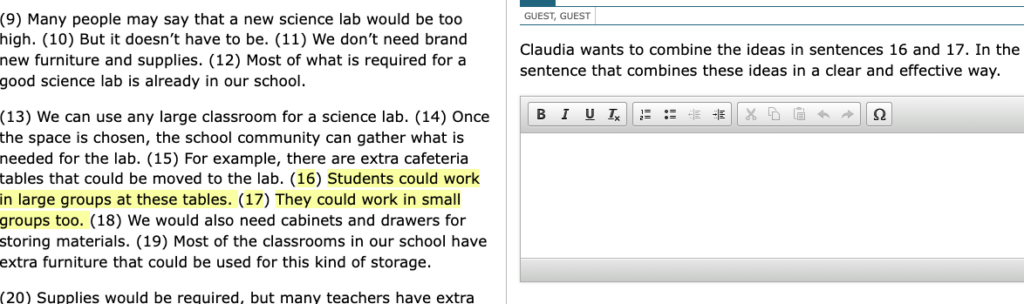

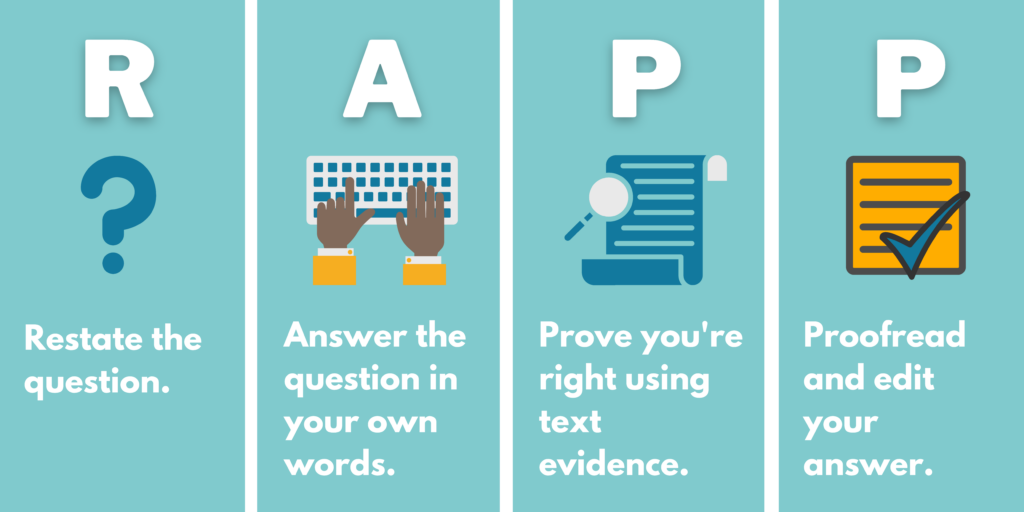

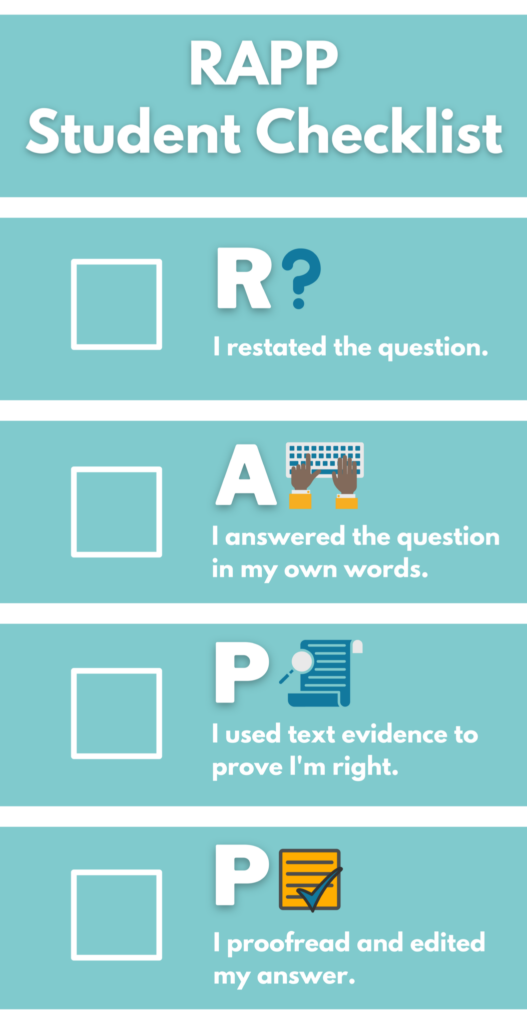

This is what I like to call, the “Speak Cycle.” Students may need to practice one or more of these steps, or the whole cycle, multiple times before moving on to writing. Speaking before writing helps students learn to organize their thoughts, look for text evidence, and also familiarizes them with proper sentence structures for opinion writing before they actually start writing. You might think, “Ok, maybe for lower elementary.” Sure, but even older students benefit from verbal practice before writing! It’s a form of rehearsal and planning.

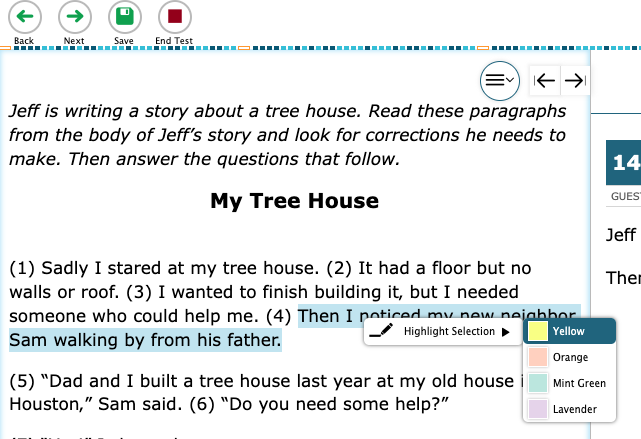

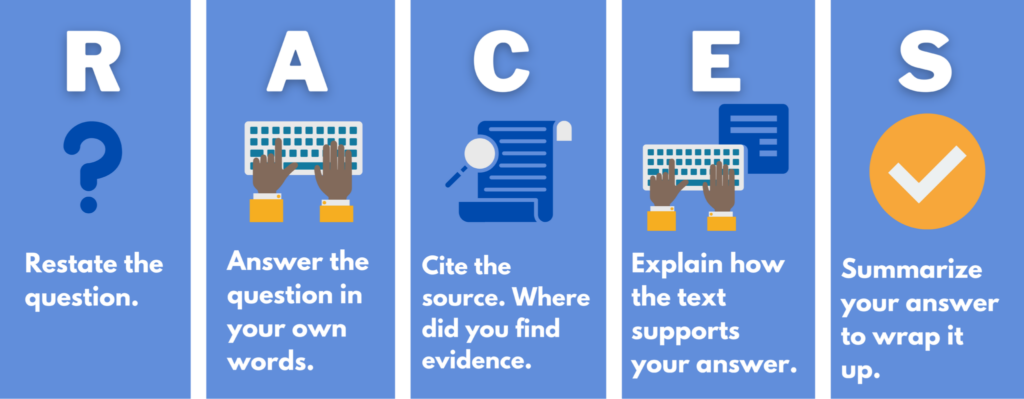

1. Whole Group: Read the text. Discuss opinions as a class. Highlight the evidence.

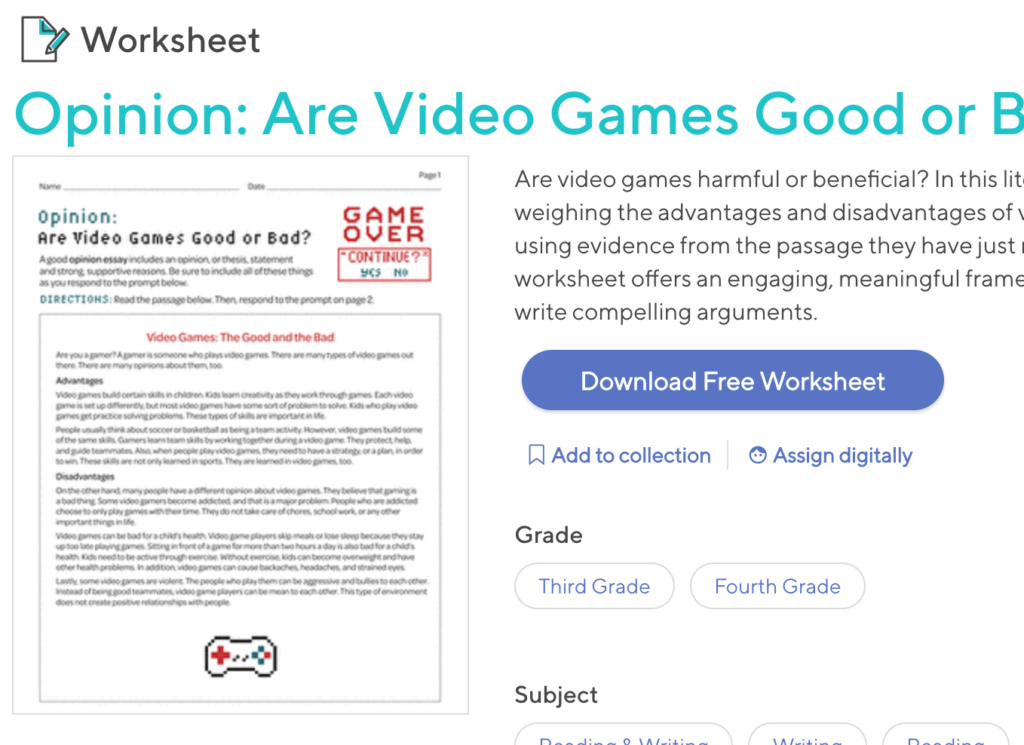

Before broaching the topic of supporting evidence for an opinion, read the text and discuss opinions. Then ask students for supporting evidence. It’s much easier to talk about supporting evidence than it is to start writing about it from the get go! Here is an example text that works well for third and fourth grade from Education.com. I recommend starting with short texts and then, as stamina improves, introducing longer texts over time.

“Today, we’re going to read a text together about ___________. We’re going to discuss our opinions on ___________ based on what we read, and I’m going to highlight facts from the text to help support our opinion.”

[Read the text] [Read the question]

“So, what are our opinions?”

[Student one offers an opinion.]

“Thanks for sharing your opinion! What information in this text led you to think that?”

[Highlight what the student references in the text. Repeat this with other examples.]

“Ok! So, from our reading today, we formed the opinion ______. And we formed that opinion because [read off highlights of the text].”

In this practice, you are showing the students how to identify and highlight supporting evidence in the text, but this is first a verbal exercise. Start with easier texts and move to more difficult texts as students become more autonomous.

You can create your own questions, but here are a few resources that offer texts with questions for opinion writing.

2. Small Group: Read the text. Discuss opinions with a small group. Highlight the evidence together.

This works best if you group students on similar reading levels. Give each student in the group the same short text that’s on their reading level. Read it together, discuss an opinion, and have students highlight the supporting facts with your guidance. Then, have students verbalize their opinions and reference the highlighted text evidence. Students should speak using the same sentence structures you want them to use when writing. Having these up as a visual is great for practice! This is all to get students ready to write.

- “I think…”

- “In my opinion,…”

- “I believe that…”

- “This is my opinion because…”

- “According to the text,…”

- “First, the author states…”

- “Second, I read that…”

- Etc.

3. Independently: Students read the text, highlight evidence, and discuss their opinion and supporting evidence with a partner or group.

Have students read a short text, think about their opinion, and highlight facts to support their opinion on their own. Students can discuss an explanation of their opinion and text evidence with a partner, or they can explain it in a small group setting. Students should still be speaking using the same sentence structures you would like them to write with.

It’s Time to Write!

Now that students are familiar with reading, forming an opinion, highlighting evidence to support their opinion, and using sentence structures verbally, it’s time to start writing. But it’s not quite time for them to write independently. First, we will model good writing for them, following a similar process to the speaking cycle.

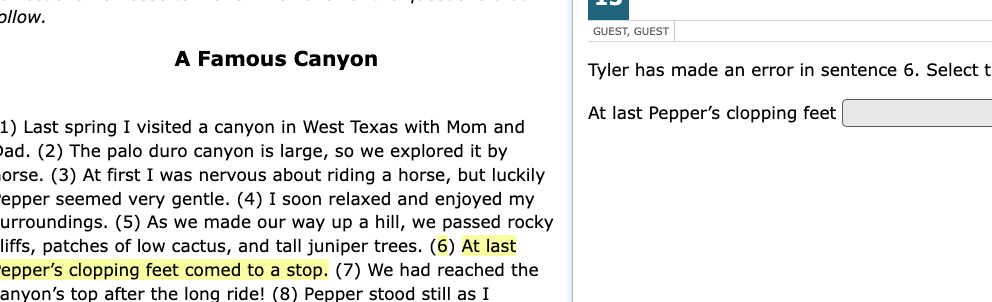

1. Whole Group: Read the text. Highlight the evidence. Model the writing for the class.

So this step is similar to step one of the speak cycle, but instead of just discussing, you are going to be modeling the writing. Here’s one formula I like to use called, “It’s Peanut Butter Jelly Time!,” and I’ve included an example using the video game article from the beginning of this post.

The Bread: The Introduction (2-3 sentences)

- Write one sentence to state your opinion.

- Write a second sentence introducing two main facts from the text that support your opinion.

“In my opinion, video games are harmful to kids. Video games can be unhealthy. They can also be too violent.” (Just an example! This is not necessarily reflective of my actual opinion on video games.)

The Peanut Butter: Paragraph 2 (2-3 sentences)

- Write a few sentences to support the first fact.

“According to the text, video games can be unhealthy if children play them for too long and don’t move around or exercise. This can make kids overweight and have health issue.”

The Jelly: Paragraph 3 (2-3 sentences)

- Write a few sentences to support the second fact.

“Sometimes, violence can make kids fight, and this can be harmful to friendships. Violence isn’t good for kids’ brains and can lead them to become bullies.”

The Bread: The Conclusion (2-3 sentences)

- Say your opinion – again.

- Say why your opinion is true – again.

“I believe that video games can be harmful to kids. Sitting for too long in front of the game can cause health problems and violence can lead to aggressive behavior. It’s better for kids to be active and be more positive and less violent.”

2. Partnered Writing: Students read the text together, highlight the evidence, and write with a partner.

It’s similar to the whole group exercise, except that students are practicing writing more independently with a writing partner/buddy. In this step, you can offer students graphic organizers or an outline template to help them remember all the elements of their argumentative writing. They can work together to write one essay or they can each write an essay and then review each other’s writing.

3. Independently: Read the text. Highlight the evidence. Write the essay.

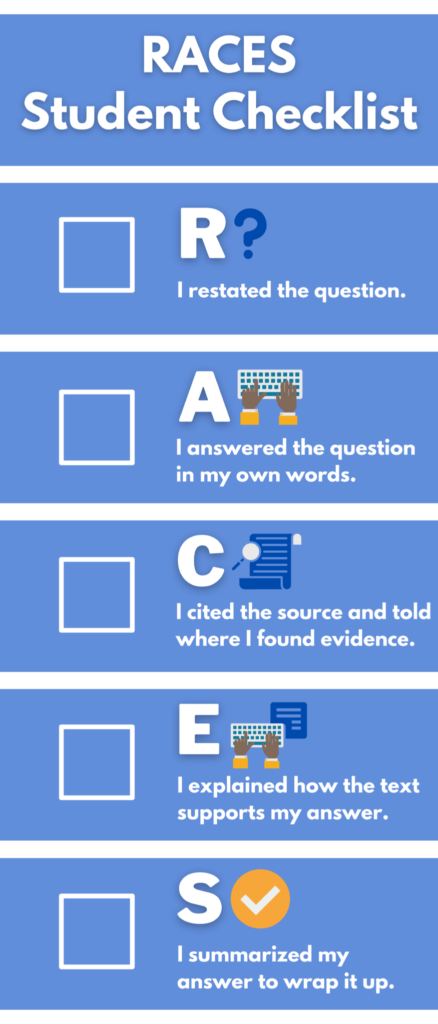

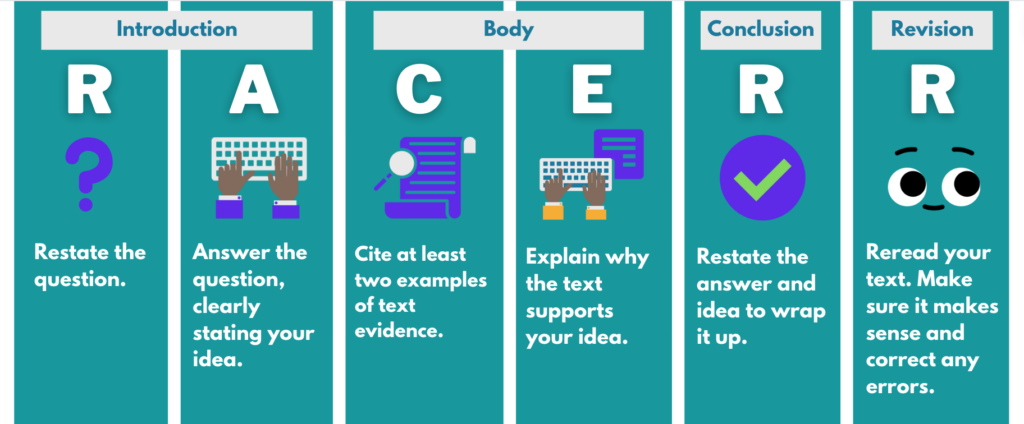

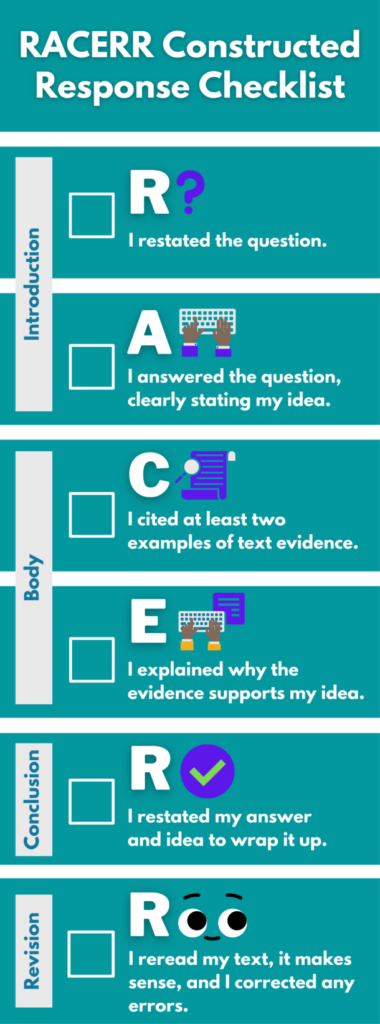

At this stage, students are practicing writing on their own. They may or may not need supports like sentence starters, graphic organizers, checklists, and visuals to reference in the room. But the goal is for students to be able to produce writing that expresses their opinion in response to a text and provide text evidence to support that opinion.

Practice, Practice, Practice!

It takes a lot of time and a lot of repetitive practice. As Miguel Guhlin references in his article, Writing Strategies: Insights from a Twitter Chat, discussing, teaching sentence structures/vocabulary, and showing examples isn’t enough. Deliberate, repetitive practice, and time, are key to teaching writing.

Do you have other ideas, strategies, or resources that have worked well for you and your K-5 students when it comes to argumentative/opinion writing? Please share them with us in the chat! We’d love to hear what’s worked in your classroom.

Additional STAAR and TEKS Articles You May Find Useful

Reading Language Arts STAAR Test Resources

STAAR Prep: A K-5 Argumentative/Opinion Writing Strategy

The K-5 ELAR TEKS and Free, Editable Spreadsheets

The K-5 Math TEKS and Free, Editable Spreadsheets

A Practical Strategy for Teaching Editing Skills

A Powerful and Easy Strategy for Teaching Text Evidence