Ready to adapt more Stoic techniques to evidence-based strategies? Applying reason to and thinking deeply about life lies at the core of Stoic philosophy. Yet, the application of reason, also known as critical thinking, can be difficult. Let’s look at heuristics that can help.

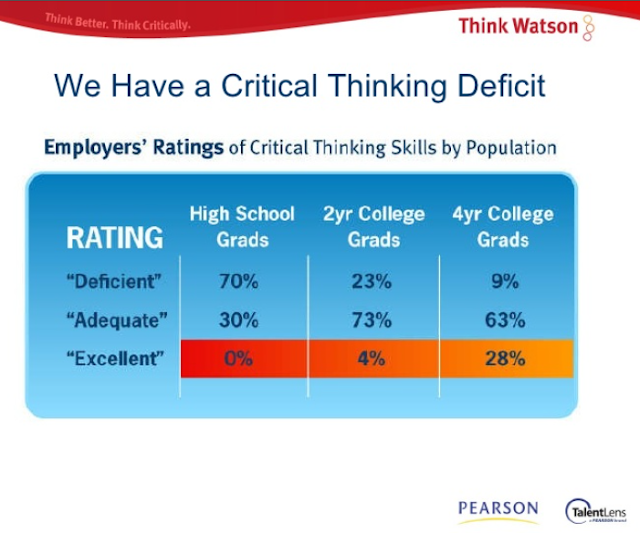

It’s easy to think we’ve mastered critical thinking in a modern age. But it’s a process each person must learn and practice daily. In spite of past efforts, it remains important that educators show their students how to think critically.

…critical thinking appears among necessary outcomes at educational institutions. Yet, “it is not supported and taught…in daily instructions.” Why? “Teachers are not educated in critical thinking” (Source: Improve with Metacognition)

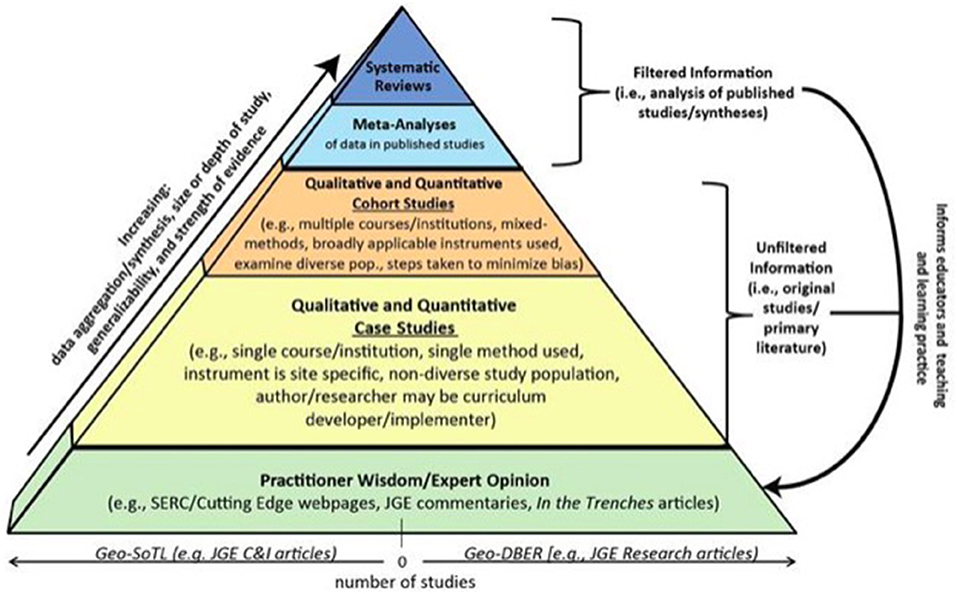

How can we better educate teachers on how to think so they can model this for students? One way might be to study evidence-based instructional strategies that work. Analysis of written evidence can prepare our minds. The diagram below might serve as one frame for analyzing what information is worthwhile.

If you’re an educator, you’re going to base your classwork on filtered information about what works. But analyzing research can be tough and not easy to do. And you can’t expect students to do this right away. First, they need to learn how to think.

Learning How to Think

When you improve how you think, you create an approach that promotes the following:

- Learning a little, trying a little (through experience or study)

- Reflecting on progress and mistakes

- Making course adjustments based on this reflection

- Trying again

One way to learn to think is through writing. As we write, we restructure what we know and seek to convey. This improves our higher-order thinking, says Robert Marzano.

Here’s what one research study had to say about it:

As an instructional method, writing has long been perceived as a way to improve critical thinking. Results indicated that the writing group significantly improved critical thinking skills. The nonwriting group did not. (source)

As a blogger, I often write list articles. That is, you make a list of points or highlight ideas. Then, you work through them one at a time, arranging them in a sequence that makes sense. It’s powerful and facilitates clearer thinking.

What’s exciting is when I come back a few days or weeks later, and ask myself, “Does this make sense? Did I explain this in the best way?” It’s exciting because my perception of what I shared has changed. That is, I’ve learned new information or had an experience. This has deepened my understanding.

Critical Thinking Processes

Being someone who thinks is hard. There are some situations that don’t need a lot of thinking to make a decision (System 1 thinking), while others do. The latter is System 2 thinking. Daniel Kahneman referred to these as fast or slow, respectively:

“System 1 operates automatically and quickly. It works with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control”

“System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it. It includes complex computations” (as cited in source)

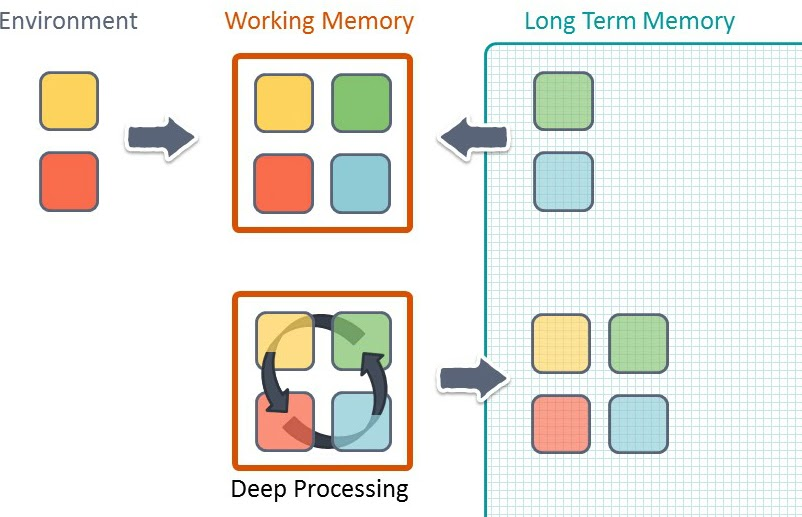

When writing, you experience slow thinking. We follow a checklist or list of steps that involve adding items to our memory. New information, mixed with long-term memory, finds a place in our minds. We leverage what we know to explain what we don’t fully comprehend. The more we experience, the more sense it makes.

Efrat Furst has a wonderful diagram that captures this:

Want to take advantage of writing as a way to enhance higher-order thinking skills (analysis, evaluation, creation)? Then don’t be afraid to give students a heuristic or checklist. I like to think of these as “formula writing.”

My Favorite Critical Thinking Heuristics

At the core of any educational experience is a need for philosophy, scientific thinking. And, of course, critical thinking processes. Go online, read social media, you will soon be awash in infographics. Each infographic will explore how to become a critical thinker. You can find some nice visuals in these resources:

- Designorate’s Five Steps of Critical Thinking

- My TCEA Design Thinking Lesson Plan Template

- The Ultimate CheatSheet for Critical Thinking

- RED Model of Critical Thinking

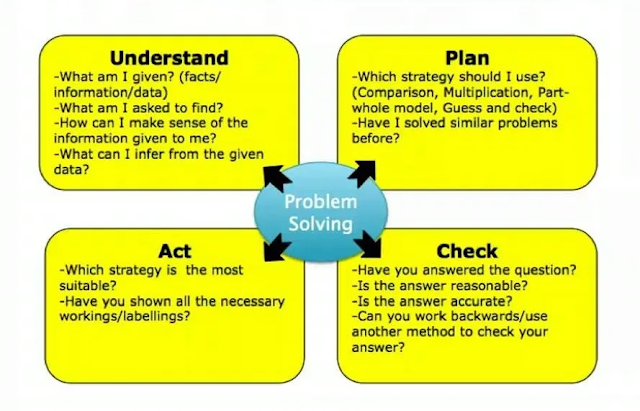

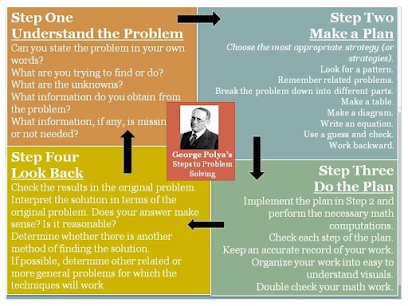

The checklists I lean towards include the following:

Or, you might prefer this version:

Polya was a mathematician. That means the problem gets translated into a mathematical problem. Then, that problem is solved. The mathematical solution is translated back into an answer for the original problem. If you’re wondering how to do that, you and I have something in common. This site might help with that.

A Simple Problem

For example, I have to fly to three different places to attend an event. That will involve staying at hotels, renting a car, and packing clothes. How might I go about solving that problem? I’ll probably start with gathering some information, using Google’s new travel tool, Google Flights.

Or if you prefer a more math-oriented concern. You’ve found you need to retile or redo the linoleum in your kitchen. If I were to write out the steps to do that, that would involve critical thinking. Fortunately, someone else already has gone through the process.

Have your own problem and solution? Apply Polya’s approach and share your solution in the comments.

Translating Thinking into Writing

Translating Polya’s critical thinking steps into a writing might be fun. You can easily make a listicle out of the process. I’ll have to do that in my next blog entry. In the meantime, do what you can to teach students to learn how to think better. You’ll profit from the process, as well. I know I have in writing this blog entry.

Feature Image Source

Photo by Juan Rumimpunu on Unsplash