We live in a personalized world. Everything from the music we listen to, the firmness of our mattresses, and the news briefings delivered to us online, it’s all personalized and tailored to our preferences. And who wouldn’t want to listen to a radio station that only plays music they like? Advances in technology have allowed companies to give a custom experience to each of its users — and those users include the students in our classrooms.

A Custom World

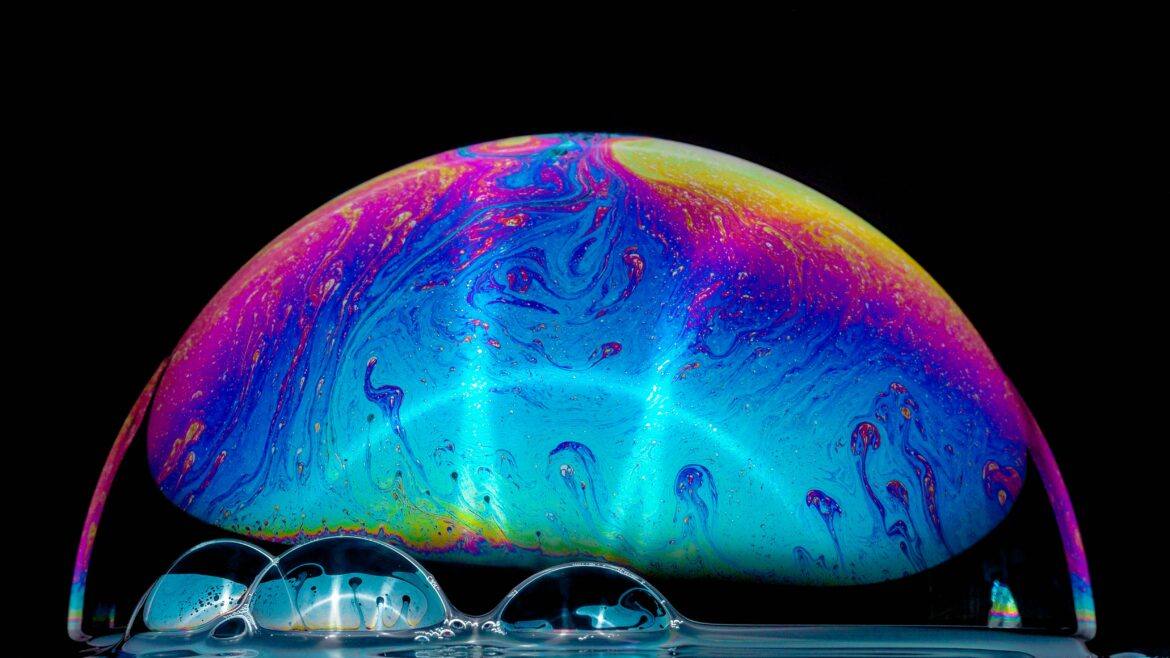

As educators, we typically hear the term “customized” or “personalized” in a positive light. Yet when seeking information, those customizations can actually translate to bias and ignorance. It’s what Eli Pariser termed the “filter bubble,” the algorithms used to provide targeted search results and tailored news feeds are creating a distorted and divided reality by only revealing one side of the story — the side you want to see.

Websites use massive amounts of data to create an experience that we’re more likely to engage and interact with. This data is often collected by “trackers” that exist on numerous websites. Google trackers can be found on the top 75% of the top million websites. These trackers do just what they say they do; they track. They track everything from the time you spend on a site to the type of computer you’re using to the time you typically wake up in the morning. All of this somewhat personal data is gathered and used without us being aware we’re even providing it. So for those of us that think we do a pretty good job of keeping our online lives private, unfortunately our actions and behaviors online can tell companies just as much, if not more, information about our lives.

For professionals dedicated to helping others search for facts and uncover the truth, this is obviously problematic.

Escaping the Bubble

Sadly, escaping this bubble is nearly impossible. Even methods that give the appearance of removing this bubble and putting the user in control of their data do very little. For example, private browsing such as Google’s “Incognito Mode” only prevents your browser history from being recorded on your computer and does not offer any additional protection such as preventing the websites you visit from collecting your information (e.g. your searches on a search engine). According to an engineer at Google, even when logged out, Google is still able to use 57 points of data to tailor your experience. Facebook’s privacy settings allow you to opt-out of seeing targeted ads, but they don’t stop the collection of data in the first place. This data and more is following us across the web, with vast implications.

So if the filter bubble is an issue, but there isn’t really a way to “pop” it, what do we do?

For better or for worse, customization is only going to get more precise and have a further reach. But unless you’re willing to go completely off the grid, we’re going to have to address this issue. This means taking a different approach to research and doing a better job of teaching students how the Internet actually works.

A Different Approach

For starters, if you’re giving students a list of “pre-approved” websites or databases, stop (for two reasons). First, by hand picking resources for students, we are robbing them of the opportunity to navigate the resources themselves. They aren’t always going to have someone there to hand pick articles for them and tell them whether they are credible or not. It’s a skill they need to develop themselves, and what better time to practice that skill than when in school? Second, there is no such thing as a 100% credible site. Even databases curate resources from the open web, so directing students to databases is a flawed practice as well. Several sites and authors that were once considered “trustworthy” and “academic” have been called into question due to bias, misinformation, or misrepresentation.

Additionally, students (and our colleagues) need to understand the existence of a filter bubble. They need to understand how companies are using data to tailor the results on nearly every site we visit. They need to understand that while their search results may have produced hundreds of “great” results, there are millions of other results they aren’t seeing. When we have students evaluate websites, encourage them to not only focus on what is in the article, but also what isn’t in the article. What perspectives are missing? What isn’t being discussed? Who wasn’t a part of the discussion?

Useful Resources

While librarians can be champions of this effort, it cannot be addressed by us alone. This is a societal issue and one that needs tackling by the community at large. While still limited, here are some resources to help teachers and librarians in this effort:

Checkology and The Sift from The News Literacy Project

Checkology is an online suite of tools aimed at making students better users of information. With lessons on algorithms, bias, identifying hoaxes, and more, it’s a comprehensive platform for addressing the many facets of media literacy. The Sift is a newsletter that shares current teachable news stories regarding misinformation, hoaxes, and other viral content.

This resource includes a series of assessments aimed at identifying thoughts and feelings outside of conscious awareness and control. This is a great tool for your older students or your staff to help become more self aware of the biases they may have.

Mozilla’s Teach the Web and Google’s Be Internet Awesome

Both organizations have an education branch focused on teaching how the web works. Yes, I recognize the irony, but they both have some excellent resources and activities.

Choose Privacy Everyday from ALA

Each year, ALA and other organizations celebrate #chooseprivacy week in May. This website hosts resources to promote privacy and confidentiality year-round. The site includes programming and lessons for elementary school through adults.