“Come look at Aida,” my dad said to me as I walked in the door of his house. It had been a long day and I was looking forward to quick pickup and then home. In the family room, my daughter hovered over a puzzle piece map. She dedicated her every moment to rebuilding a map of the United States. She had a few pieces left in her hand. My dad chuckled at my open mouth and wide eyes.

“I taught map-reading at Ft. Benning, Georgia,” he reminded me. “Well, it’s obvious map skills skipped a generation.” I smiled at Aida as she put the last piece in place, snuck a glance up, then flipped the board upside down. Next level gaming. One more time. My dad called out the time it took her to complete the puzzle to her.

An introduction to maps at a young age can yield dividends. Today, Aida makes maps to track health concerns among immigrant populations.

I don’t recall constructing or playing with puzzle maps. But there is many a time, lost on the road, that I wish I had. Geospatial thinking remains important today. That’s why I thought to share some map-making resources and tools with you.

Geospatial Thinking

“Geospatial thinking is critical thinking,” some say (source). In fact, it’s suggested that the following is true:

Geospatial reasoning matches the patterns of observed data to the models, oftentimes maps or other geospatial displays, to answer questions of what is or might be happening. Reasoned explanations for “how” and “why” require additional context and data.

Without geospatial thinking, it is easy to still create beautiful data displays. The problem is, they may mislead. As the authors point out, “Expert tools wielded by analysts who lack critical thinking skills will result in ‘nonsensemaking.'”

Did You Know?

Map making spans various areas of interest. GeoscienceLearners is an initiative created to engage young students interested in geoscience fields. This initiative seeks to increase diversity and inclusion in the geosciences and build resources for geoscientists and aspiring geoscientists. Learn more online.

Find the online resource at the GeoSciencesLearners Database. You may contact the creators at geoscienceslearners@gmail.com if you have any questions or would like them to facilitate a presentation.

How do we better prepare our children in this area? The answer is simple: Study map-making motivations and then make maps. Analyzing existing maps and asking questions is also important. Ask questions that challenge the cartographers’ motives and goals. This two-step approach seems easy, but represents the beginning for many young people like Aida.

Step #1: Map Analysis

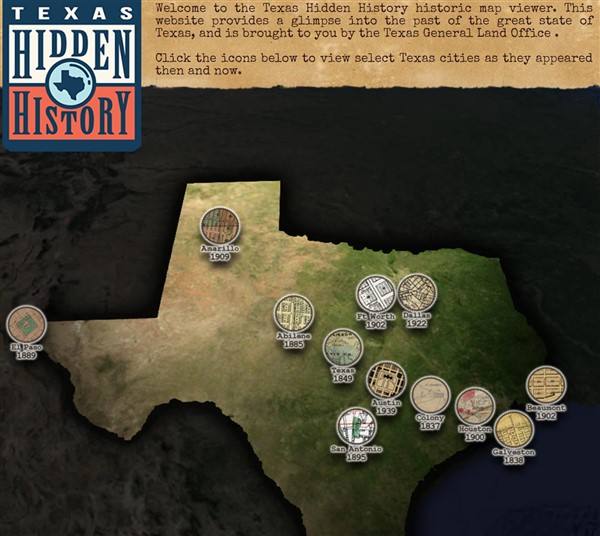

To analyze maps, you first need maps to study and critique. There are many such resources, as a quick perusal of TCEA’s blog archive will reveal. No doubt you may already be familiar with the Texas General Land Office’s collection of interactive content. It offers an interactive map of Texas as well.

Another new and exciting resource is David Rumsey’s Map Collection. It describes itself in this way:

The David Rumsey Map Collection Database has many viewers and the blog has numerous categories. The physical map collection is housed in the David Rumsey Map Center at the Stanford University Library. Take a virtual tour of the map center.

The historical map collection has over 100,000 maps and related images online. The collection includes rare 16th through 21st century maps of America, North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Pacific, Arctic, Antarctic, and the World.

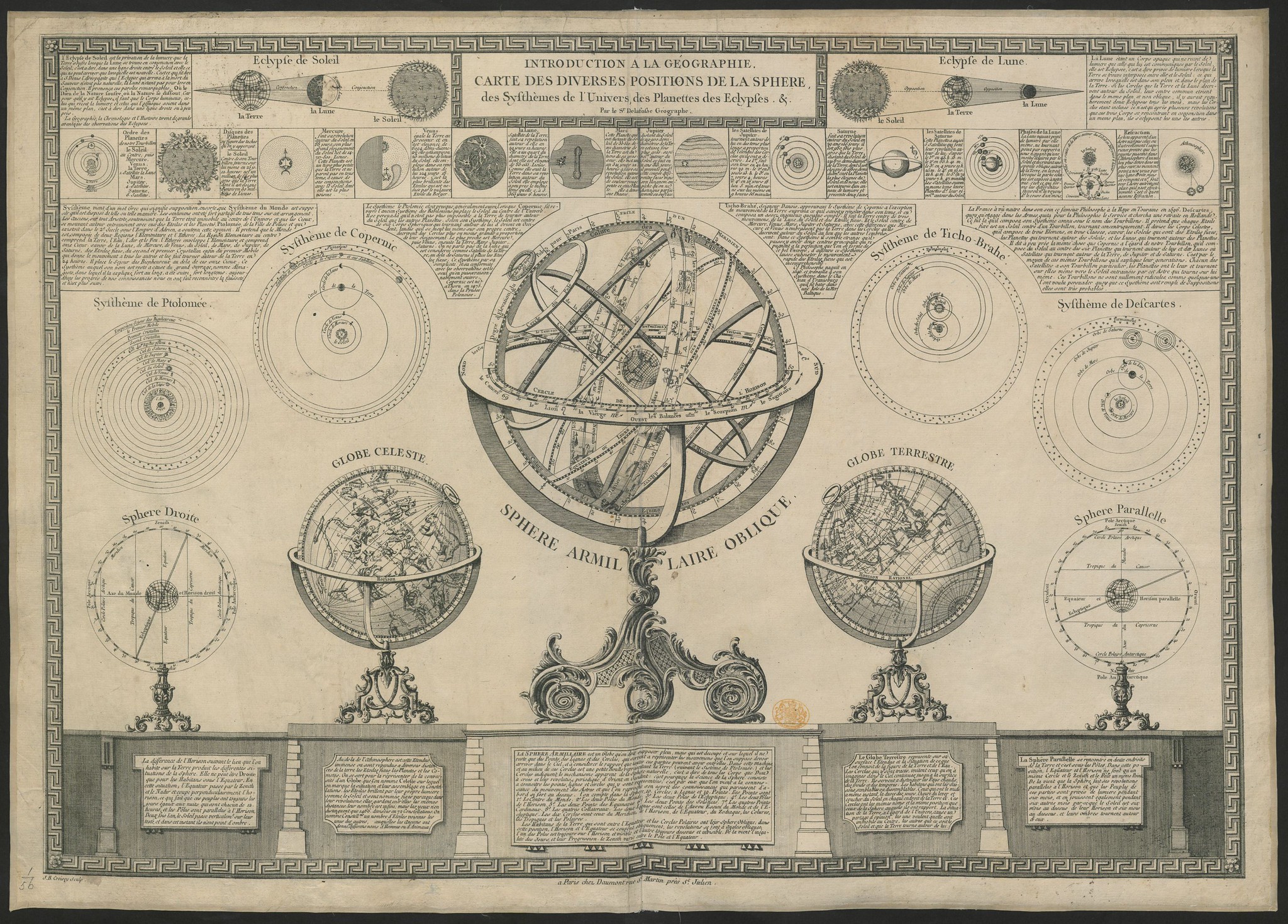

Other online map archives include the 40,000 collection from the British Library. You can see one of the many examples below:

“Introduction à la Géographie; Carte des diverses positions de la S., des Systèmes de l’Univers, des Planetes, des Éclipses … Par le Sr Delafosse.” View it in the British Library collection.

One point to keep in mind as you look at the effort of these map creations is that some maps are abstract while others are a bit more accurate to reality. Students in K-12 do learn about maps in specific ways, as Jean Piaget theorized. They move through three stages, including topographical, projective, and euclidian. What’s more, research shows that “children are able to understand map symbols and that they represent places and things on a map.” However, “it is more difficult for them to read and interpret more abstract symbols and to understand the relationships between the symbols” (Source).

Step #2: Map Creation

Making maps can be a lot of fun. Here are a few approaches to get your students started creating maps.

Approach #1: Fantasy Maps

Reading Guy Antibes multi-book series of young adventurers, great for secondary students, I was reminded of fantasy map making. Want to hook students into cartography? Start with fantasy map making. There’s this great YouTube series on How to Draw a Fantasy Map. I love how the creator of the SellSwordMap videos creates his first draft of a map. Who knew, right?

That’s right, scatter some beans on the page. This may be a fun way to engage students in map-making. You can find pretty neat online tools to make maps, but dropping beans on a page is engaging.

Approach #2: Minecraft Maps

Students love Minecraft, and it’s not much of a stretch to map out virtual space. Students can create maps on paper, then make their creations come alive online in Microsoft’s Minecraft for Education. Minecraft also makes map-making a part of the experience.

Approach #3: ArcGIS Online

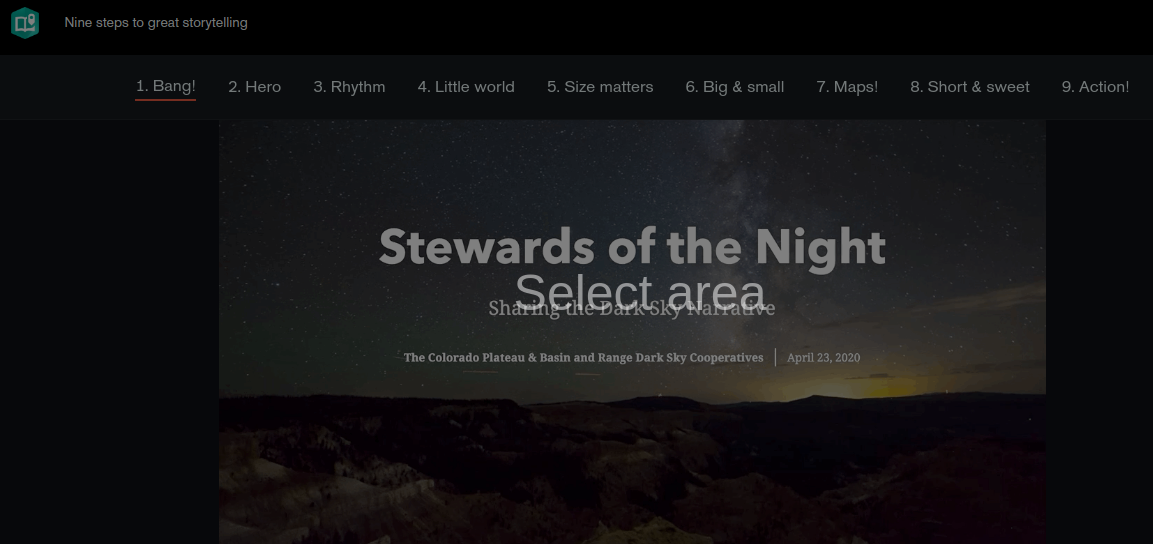

You can create amazing Story Maps with the super powerful ArcGIS Online tool. You and your students can design “inspiring, immersive stories by combining text, interactive maps, and other multimedia content.”

The Story Maps website offers great suggestions for getting started, which you can adapt for use with your students. Follow these steps to get started:

- Create a free, public account with ArcGIS Online

- Visit the Story Maps Apps website

- View the Gallery of Examples

Approach #4: Google Tour Builder

Getting started with Google Tour Builder isn’t difficult. My esteemed colleague, Eric Curts at Ctrl-Alt-Achieve blog, describes Tour Builder in this way:

Google Tour Builder allows you and your students to create virtual tours on a map, including locations, images, videos, descriptions, hyperlinks, and more. These tours can be used in any subject area such as retelling the events from a novel, tracing the locations of a historical event, visiting different biomes or landforms around the world, and more. Tours can be viewed by others in Tour Builder, or even imported into Google Earth for a full 3D experience.

Isn’t that amazing? Find more information on learning how to use Google Tour Builder at Eric’s website or check out this overview.

There’s a lot more to discuss about geospatial and critical thinking than what we have covered here. You can begin your journey and learn more along the way. Don’t be afraid to invite your students on your voyage of discovery.

Feature image: Melissa & Doug USA Map Puzzle 45 pcs available online.