Seventy-six percent of third and fourth grade teachers rated their college education to teach writing as low. Seventy-one percent of teachers say that they receive minimal to no preparation to teach writing. To address that, Natalie Wexler made some recommendations on how to deal with the problem. Let’s explore some of the insights and writing strategies Wexler shared in a January 11, 2023 Twitter chat.

Some Quick Background

Natalie Wexler, a co-author of “The Writing Revolution,” shared her insights in a January 11, 2023 Twitter chat. She was participating as a guest in the #BmoreEdChat on Twitter. Wexler has taken aim at teaching reading and writing. With Judith C. Hochman, she points out that teachers in K-12 schools lack a roadmap.

Absent a roadmap, how does one know how to teach writing? What writing strategies are available? To clarify the path ahead, Hochman and Wexler suggest explicit writing instruction. This term accomplishes four actions:

- Enables writers to identify gaps in their knowledge.

- Boosts reading comprehension through construction of improved syntax in their own writing.

- Enhances speaking as a result of more complex syntax and sentences.

- Improves organizational and study skills, such as paraphrasing, note-taking, summarizing, and outlining.

Writers engage most of these actions with differing degrees of success. The Hochman Method suggests a series of exercises that target skills not mastered. Then, providing feedback that identifies mistakes and monitoring student progress. As you might imagine, sentences, grammar, and content are integral.

Natalie Wexler makes some observations in her tweets worth reviewing in more detail.

Observation #1: Content-Area Writing Works

“We need to weave writing instruction into content-area instruction,” Wexler says. She asserts that students will comprehend material better. And, this translates into long-term memory retention.

“When students write about what they’re learning in science, social studies, and math, they understand and retain material better. (source)

She refers readers to a meta-analysis supporting that assertion. It is “The Effects of Writing on Learning in Science, Social Studies, and Mathematics:”

…writing about content reliably enhanced learning (effect size = 0.30). It was equally effective at improving learning in science, social studies, and mathematics as well as the learning of elementary, middle, and high school students.

Source: Graham, S., Kiuhara, S. A., & MacKay, M. (2020)

Writing DOES improve learning in core content areas at all grade levels.

Why is writing effective? “Writing about content material facilitates learning by consolidating information in long-term memory,” explain Graham and his colleagues, describing a process known as the retrieval effect. As previous research has shown, information is quickly forgotten if it’s not reinforced, and writing helps to strengthen a student’s memories of the material they’re learning. (source)

Observation #2: Outlining Can Help

Cognitive load means your brain can handle only so much when processing new information. The key is to transfer as much as possible to long-term memory. In this way, working memory can be devoted to new information.

Writers are managing a lot of things when engaged in authoring a piece. They have to track “letter formation, spelling, word choice, and sentence structure” (source). One way to ease cognitive load involves creating “clear, linear outlines.” Outlining, you may recall, a well-established deep learning strategy:

Involves identifying the main ideas and rendering them in one’s own words. The core skill is being able to distinguish between the main ideas and the supporting ideas and examples.

Outlining assists students in building relationships between ideas and concepts. Outlines that students make of their writing and what they are trying to write about, enable students. Wexler says it assists students with:

- organizing their thoughts,

- avoiding repetition, and

- staying on track.

The goal is to get more content and writing syntax into long-term memory. Another way to move information students need into long-term memory? Learning how to put sentences together.

Observation #3: Learn Syntax

Wexler doesn’t suggest we learn complex syntax of the written word for fun. Rather, the benefit gained includes improved comprehension. You can read the study she cites here. As a result, students engage in two writing activities. Those include:

- Sentence combining. Put a few simple sentences together to make a complex sentence.

- Sentence reduction. Break up a complex sentence into several simple sentences.

Wexler and Hochman have a wealth of suggestions in their book, “The Writing Revolution.” You can also find a website of the same name that’s worth a visit as well.

In the meantime, here are some more ideas for your consideration.

Strategy #1: Write with Students

If teachers feel ill-equipped to teach writing, one way to equip them is by getting them to write with their students. Freewrites and brainstorming sessions go much further than writing in a worksheet.

An approach that has worked well for the author? Find age appropriate text, including non-fiction, poetry, short fiction. Then, write with your students in that style so they can see it develop and improve, one word, one sentence at a time.

This guide from Kenneth Koch still works.

Strategy #2: Practice, Practice, Practice

Another key idea of writing workshop is not only providing feedback but also offering examples to lessen students’ cognitive load (source). You do that when you take these actions:

- Teach sentence structures and vocabulary.

- Provide exemplars that illustrate these things.

- Lead discussions on the subject.

But providing these isn’t enough. Students need repeated practice with them. Natalie Wexler says in “Writing and Cognitive Load Theory,” that:

Students need more than direct instruction and worked examples to become competent writers. They need ‘deliberate practice’: repeated efforts to perform aspects of a complex task in a logical sequence, with a more experienced practitioner providing prompt and targeted feedback

Strategy #3: Give One-On-One Feedback

If teachers don’t know how to manage writing workshops in their classroom, they have a problem. They won’t be able to provide “prompt and targeted feedback” to writers in their care. As a writing workshop facilitator, a few words, one on one, can make a big difference.

Celebrating Success

“I notice you wrote the same sentence over and over to make a paragraph. Could you write another sentence that grows the idea in this first one?” That’s a paraphrase of the conversation I had in Spanish with one fifth grader. The young writer wanted to please, and in a few months, was writing “real” paragraphs. He had seen me writing and knew what he was doing was less. He didn’t know or have the vocabulary to do the same.

Additional Writing Strategies

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen,” says John Steinbeck. Any student sitting at a blank page soon finds out an ugly truth.

There’s no muse whispering in their ear, “Write this mellifluous sentence.” Instead, the muses paint the shape of text in our imagination.

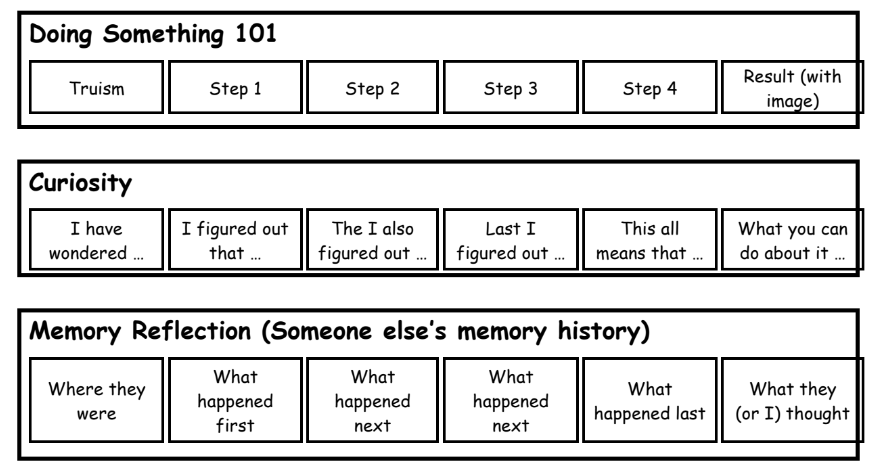

From Single Paragraph Outlines, that “The Writing Revolution” suggests, to text structures – planning ahead is mission critical.

With this in mind, encourage writers to:

- Write in a paper notepad or journal (then transfer to a digital medium like a blog) to track “new to them” information and ideas.

- Reflect on old writing and ideas. Revisit those old blog entries in that notepad to get fresh insights. The entries didn’t change, we did.

- Juxtapose opposing ideas and try to mash them together. In doing so, you can get something fresh.

- Identify the formula, or “text structure,” to any piece (e.g. The List Article).

As a writing teacher, I work to awaken students to what’s write-worthy. I encourage them to learn how to edit their own work. What are some ways you can make these strategies come alive in your classroom?

Feature Image Source

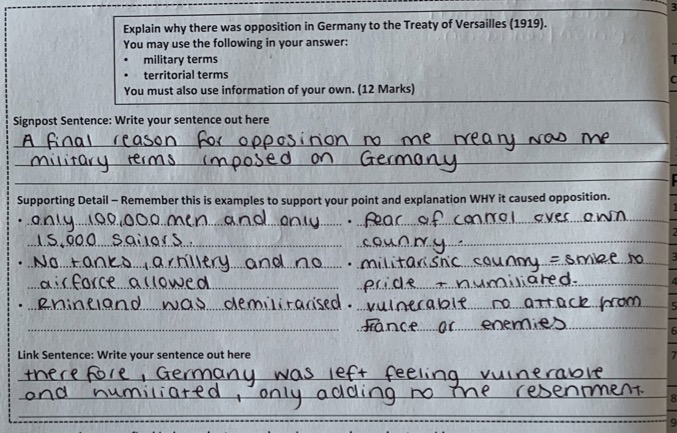

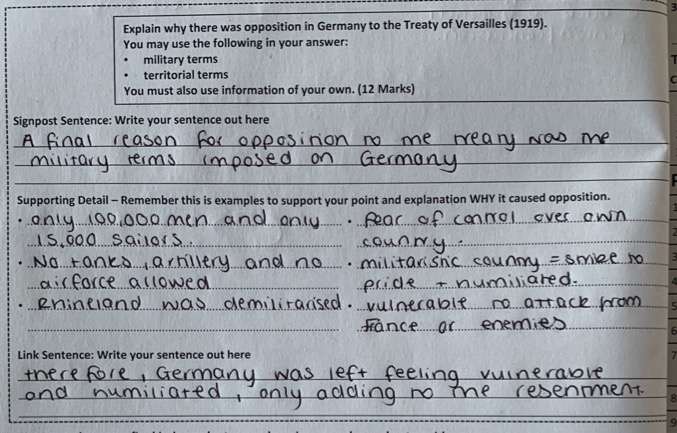

Screenshot by author of The Single Paragraph Outline