Over my 40-year career in education, I have come to recognize that what I was taught back in college about being an effective teacher is not necessarily true today. It’s not just because times have changed (they have), students have changed (they have), or the world has changed (it has). It’s because, over the past 30 years, more research has been done on what works best in teaching and learning than in all the years before that. And the results of all of that research are startling, to say the least. One of the most astonishing findings has to do with the value of following Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The History of Bloom’s

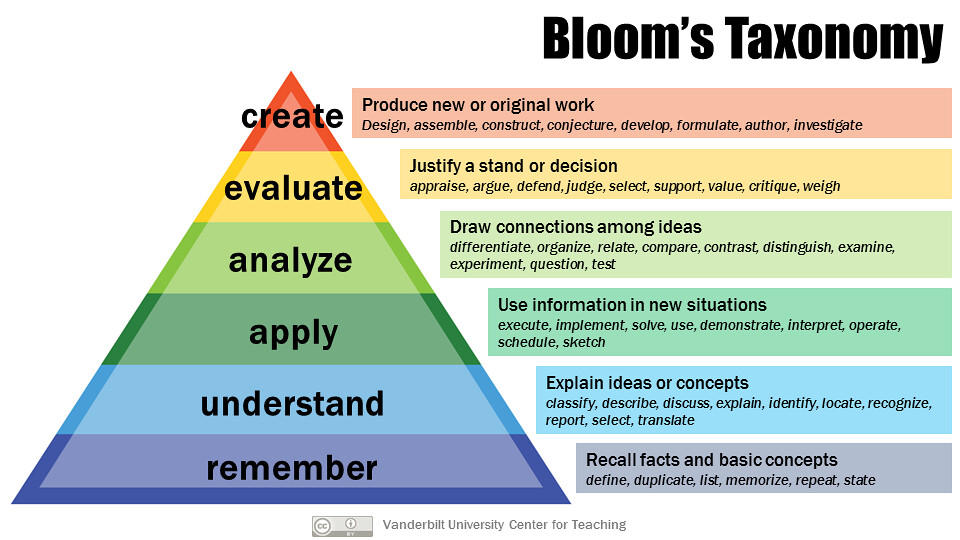

The taxonomy was created in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom and some of his colleagues as a way to leave behind behaviorist theories of learning that were being used at the time (memorization, rote learning) and embrace higher-order thinking skills. They incorporated aspects of cognitive, affective, and psycho-motor domains into the taxonomy to make it more all-encompassing. It was a radical change in how educators were taught to teach. Then, in 2001, Anderson and Krathwohl offered a revision to Bloom’s, indicating that “in the cognitive domain, creation appears as a higher-order process as compared to evaluation.”

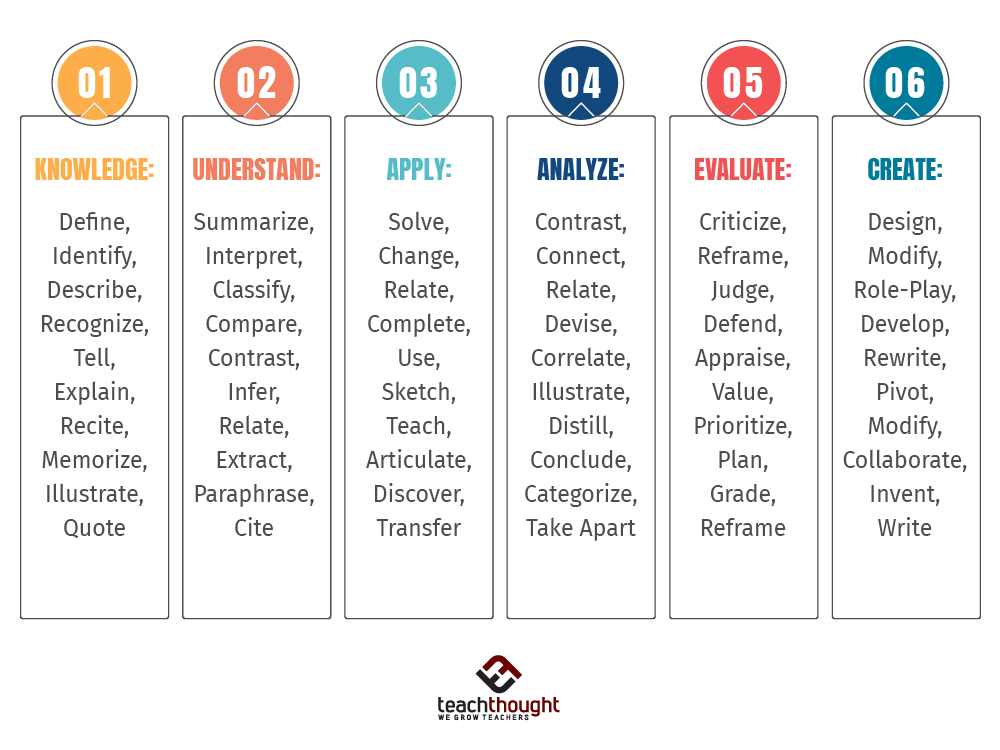

Bloom’s Taxonomy is easy to implement. We are all familiar with the “verb chart” that lets us select the level of thinking we want our students to work at. We pick a content standard, decide what level it is best learned at, find a verb at that level in the chart, create the learning activity, and we’re done. But is this approach still valid today?

Why Bloom’s May Not Be the Best Approach

The first reason to reconsider using Bloom’s Taxonomy in the classroom has to do with how the brain works. Thinking does not operate within hierarchies (as outlined in the taxonomy). All of these “levels” happen simultaneously in a variety of places in the brain.

The second reason to stop relying on Bloom’s is that it was created before rigorous research into its effectiveness was put in place. At more than 60 years old, the taxonomy is simply not supported by any empirical research on learning. The only piece of this hierarchical approach that is validated today is the existence of factual-conceptual knowledge, often called prior knowledge. But there is no clear research on its basic assumption that there are lower- and higher-order thinking skills. The brain doesn’t look at a problem to be solved and decide that it only needs a lower-order process.

The third reason Bloom’s may not be the approach you want to follow in your classroom has to do with new research on the social relation of persons in the creation of knowledge. The taxonomy does not consider the learner and the differences that each learner brings to the table. Motivation, their intellectual values, their past experiences with the content, their differences in cognitive processing: none of these are considered. The approach is based on the belief that all learners are at the same place in their learning, which is inherently false. In short, Bloom’s Taxonomy focuses on abstract cognitive domains and not on the individual learner. It is teacher-centered and not student-centered.

Conclusions to Take Away and Next Steps

I realize that this blog may shock some educators. And for that, I’m sorry. But we want to put our time, effort, and focus into instructional strategies and approaches that we know will work best for our students. And I believe that we must stay current with what the latest (and verified!) research says in order to do so.

So what might your next steps be? Make time to examine what the latest and best research says about effective teaching and learning. TCEA has a series of blogs on instructional strategies that have been proven to work, as well as several online, self-paced courses that will help you dive into how to apply the best approaches in your classroom. Be open to new ideas and new ways to help your students master the content. Question the strategies that are your “favorites” and ensure that they are based on valid, current research. And talk with your colleagues and administrators about getting more professional learning on the most effective teaching methods.

Research and Supporting Articles

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review Of Psychology, 52(1), 1

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a Psychology of Human Agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, (2). 164.

- Barney, Jason (2021). Breaking Down the Bad of Bloom’s: The False Objectivity of Education as a Modern Social Science.

- Berger, Ron (2018). Here’s What’s Wrong with Bloom’s Taxonomy: A Deeper Learning Perspective.

- Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

- Briñol, P., & DeMarree, K. G. (2012). Social metacognition. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Case, Roland (2013). The Unfortunate Consequences of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 85-107). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Efklides, A. (2006). Metacognition and affect: What can metacognitive experiences tell us about the learning process? Educational Research Review, 13-14.

- Kim, Y. R., Park, M. S., Moore, T. J., & Varma, S. (2013). Multiple levels of metacognition and their elicitation through complex problem-solving tasks. The Journal Of Mathematical Behavior, 32(3), 377-396.

- Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive Theories. Educational Psychology Review, (4). 351.

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting Self-Regulation in Science Education: Metacognition as Part of a Broader Perspective on Learning. Research In Science Education, 36(1-2), 111-139.

10 comments

Reading requires using many different skills. Executive functions are some of the skills required in reading, a working memory , planning, organization, time management, etc. Bloom’s taxonomy improves “Executive functions .” “Knowledge ” , identify, label, match, list, improves working memory. “Comprehension “, describe, explain, order, improves organizational skills. Planning is used in “synthesis “, rearrange , predict, reorganize parts into a whole. Time management must be used in “application “, and “evaluate “, construct, demonstrate, illustrate, prioritize, and choose. Let’s question heuristic strategies, and adhere to improving executive functions.

I learned Bloom’s as an undergrad and then again in grad school. In both cases the benefits was in helping educators to write objectives. There were designed to help us articulate what we were hoping to achieve in our instruction. It’s value to me is in helping eductions to think about what their doing and why they are doing it. I don’t feel like that value has faded. The other thing that Bloom and Krathwohl did was decide learning into 3 domains (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor). Once again to help us conceptualize what we are teaching and why are we teaching it that way?

I use Bloom’s verbs as word of the day in my 3rd grade class. They should be familiar with the verbiage of questions that will be asked of them especially on MAP and STAAR tests. I found it to be beneficial.

I think this is a very good use of Bloom’s, Melisa!

I’d add another reason to avoid the Bloom approach: trying to force your course to fit it can be a lot of work. I’ve done multiple educational trainings that have told me to base my course on Bloom’s taxonomy. It never felt like a good fit (I teach philosophy with an emphasis on critical thinking). Yet I trusted the people giving these trainings and wasted time trying to incorporate Bloom’s ideas into my courses. I found your post because I’m doing yet another training that’s going to encourage me to use Bloom. So I did my own search for empirical evidence of the approach’s efficacy and, like you, I’m coming up completely emptyhanded. Nothing, zilch, nada.

Anyway, thanks for this useful post. I’m surprised there aren’t more people making these important arguments.

Just here to point out that Anderson & Krathwohl’s revision occurred in 2001, not 2021. Thanks for the interesting post!

Thanks, Sophie. I’ll make that correction!

There’ still value in using Bloom’s to push students beyond repeating what they’ve read. When I ask for a paraphrase, some students will literally copy and paste a quote from the source. Referencing Bloom’s different types of thinking helps them see how developing your own understanding of a source leads to stronger critical thinking skills.

I always tell them that all types of thinking are important and useful, and we shouldn’t rely on one or two levels.

I struggle with lower-order thinking, but rock higher order thinking. Some students can repeat back precisely what they’ve heard or read but have no idea what it means or how to use it. That’s where Bloom’s comes in: use all of the levels.

I have taken on a very difficult concept to introduce to college students. I interviewed 10 students for a research project. I designed the interview with Blooms Taxonomy woven into each step of this process. Eureka! By the end of the interview each student was able to create their own scenario using the new and complex concept definition. Blooms isn’t a religion, but it certainly works for introducing a heretofore undefined concept!

I’m not convinced that Bloom’s Taxonomy claims to do much of what is stated here. Most strikingly it’s a hierachy to demonstrate levels of understanding, not levels of thinking. Recognising that students are at different stages in their understanding encourages teachers to differentiate their instruction, which in my experience has to be a good thing.