As educators return to school, we are hearing the phrase “learning gap” a lot. I mean, A LOT. Administrators are understandably worried about the lower-than-average results on the different state assessments. School boards are being pressured by upset parents and government officials to “get the scores up.” And caught in the middle are the teachers who must make sense of how to help students grow academically this year more than ever before.

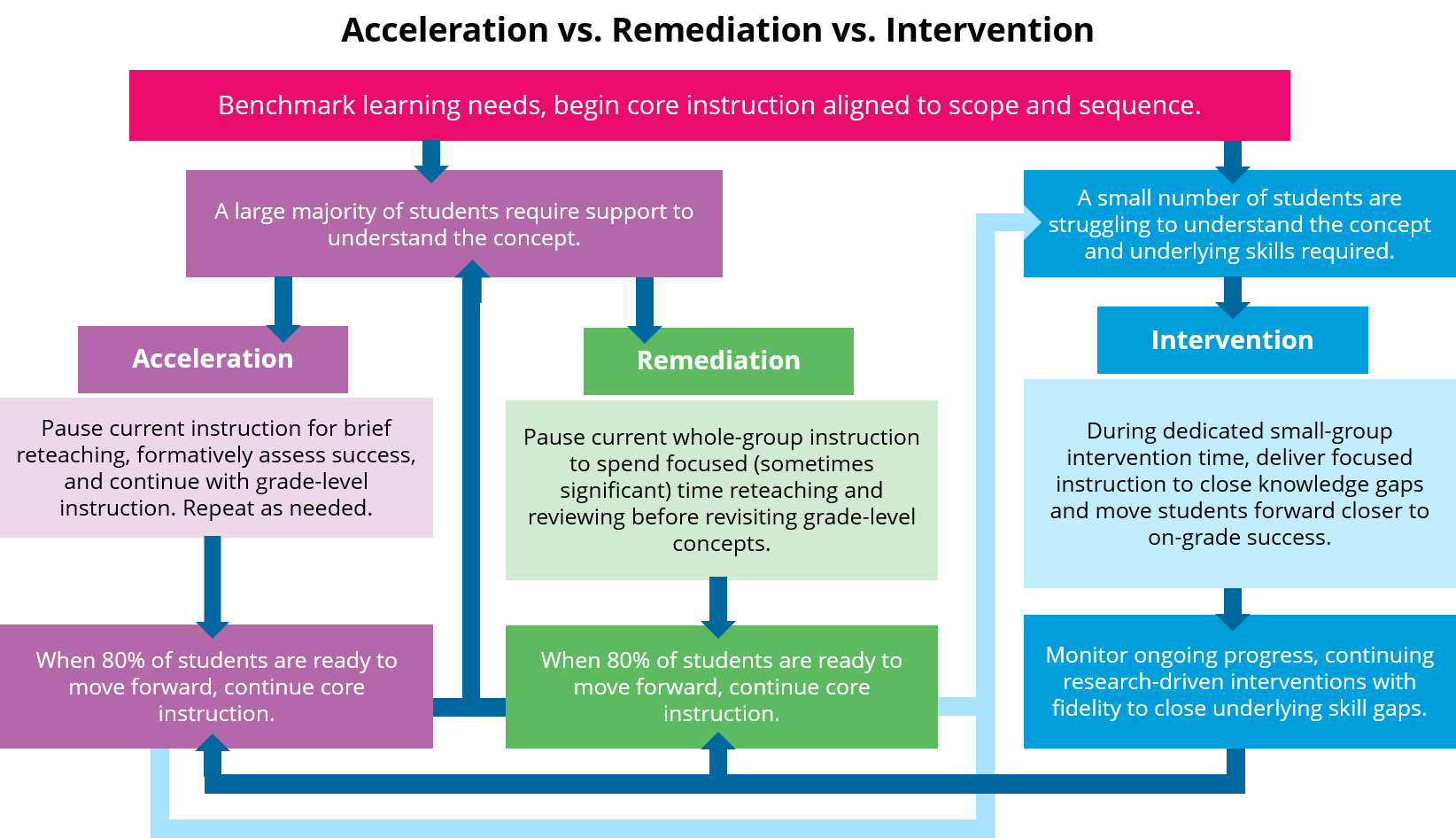

Many different approaches are being tried, and lots of education-ese buzz words are being thrown around. In talking with teachers these past few weeks, three words keep rising to the top of the list: acceleration, remediation, and intervention. Let’s take a look at these three and see what each means and when is the best time to use it.

It’s important to note that all three strategies have at their core helping struggling students to achieve academic success. However, the differences between them “are critical to determining what sort of environment, time, and approach might be required to best serve your students.”

First Things First

Before starting a new content unit and deciding what instructional approach is best for a particular student or group of students, it is necessary to benchmark their learning needs. Simply starting at the beginning of the unit and working our way through it does not guarantee academic growth. Instead, you must gather data that can help you answer the following questions:

- What do they already know? (Here, the data must be broken out by individual student to determine any necessary grouping strategies.)

- How deep is their understanding of the topic? (Are they at surface, deep, or transfer learning levels?)

- What are they confused or have misconceptions about?

- What other roadblocks may be in the way of their mastering the content (such as poor vocabulary or low reading level)?

With answers to these questions, you can now think about the best approach to take.

Acceleration

“Acceleration is the concept of teaching grade-level material but weaving in stopping points periodically to address a small missing piece in fundamental understanding before popping back up to the original skill” (source). Acceleration is best used when the majority of the students in the class need help with a particular topic or skill. The biggest benefit of this strategy is that is stops the cycle of constantly reviewing below-grade level content with struggling students, keeping them forever behind. And, new research from TNTP (The New Teacher Project) indicates that acceleration does indeed work since the brain is flexible enough to allow and thrive in these short pivots in instruction. The research has shown that it can help to combat years of academic inequities.

Please note that the term “acceleration” is often also used to describe the process of having gifted students move through traditional curriculum at rates faster than normal. This can be done with grade-skipping, early entrance to kindergarten or college, dual-credit courses such as Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs, and subject-based acceleration (like when a fifth-grade student takes a middle school math class). This is not the acceleration being discussed in this blog.

Accelerated learning strategically prepares students for success in current grade-level content. It readies students for new learning. Past concepts and skills are addressed, but always within the purposeful context of current learning. It is forward looking, not backward.

For acceleration to be successful, the teacher must access students’ prior knowledge and then teach prerequisite skills that they must learn at a pace that allows the students to stay engaged in grade-level content and lays a foundation for new academic vocabulary. It provides laser-focused instruction on the specific skills and content that students need in order to learn the new grade-level material at hand.

Here are two examples of acceleration:

- In fourth grade math where students are to learn multiplication of fractions by a whole number, the teacher must first quickly address their unfinished conceptual understanding of what fractions represent.

- In an English/Language Arts class, ninth grade students who are reading A Raisin in the Sun might first need to quickly build their historical knowledge of redlining and the Great Migration. Both could be done easily with non-fiction texts that support the novel.

Remediation

Remediation has come to mean “teaching again,” having the teacher focus on content that students did not learn in previous years as they should have. This typically means that struggling students are working on below-grade level content a large portion of their time. Remediation focuses on drilling students on isolated skills that generally have little to do with the current topic being studied.

Most often, remediation works best at the lower grades. Once students have moved on to more complex subjects without the necessary background knowledge and skills, remediation becomes a vicious cycle of them never catching up. For it to be successful at all, the teacher must help students learn the content in a new way than was previously used with them. Just doing the same activities or teaching it as the same process will not work.

Intervention

Educators are probably most familiar with this approach as we see it in two common models: response to intervention (RTI) and multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS). It is a “formal process for helping students who are struggling, where research-based instructional approaches are implemented around very specific skill deficits and where progress is regularly tracked” (source). Where acceleration and remediation are often done with up to 80% of a class, intervention is usually done with a much smaller percentage (15% or less). That means that intervention can be targeted and tailored for each student’s individual needs, which often requires a team of educators to work with each child.

What It All Means

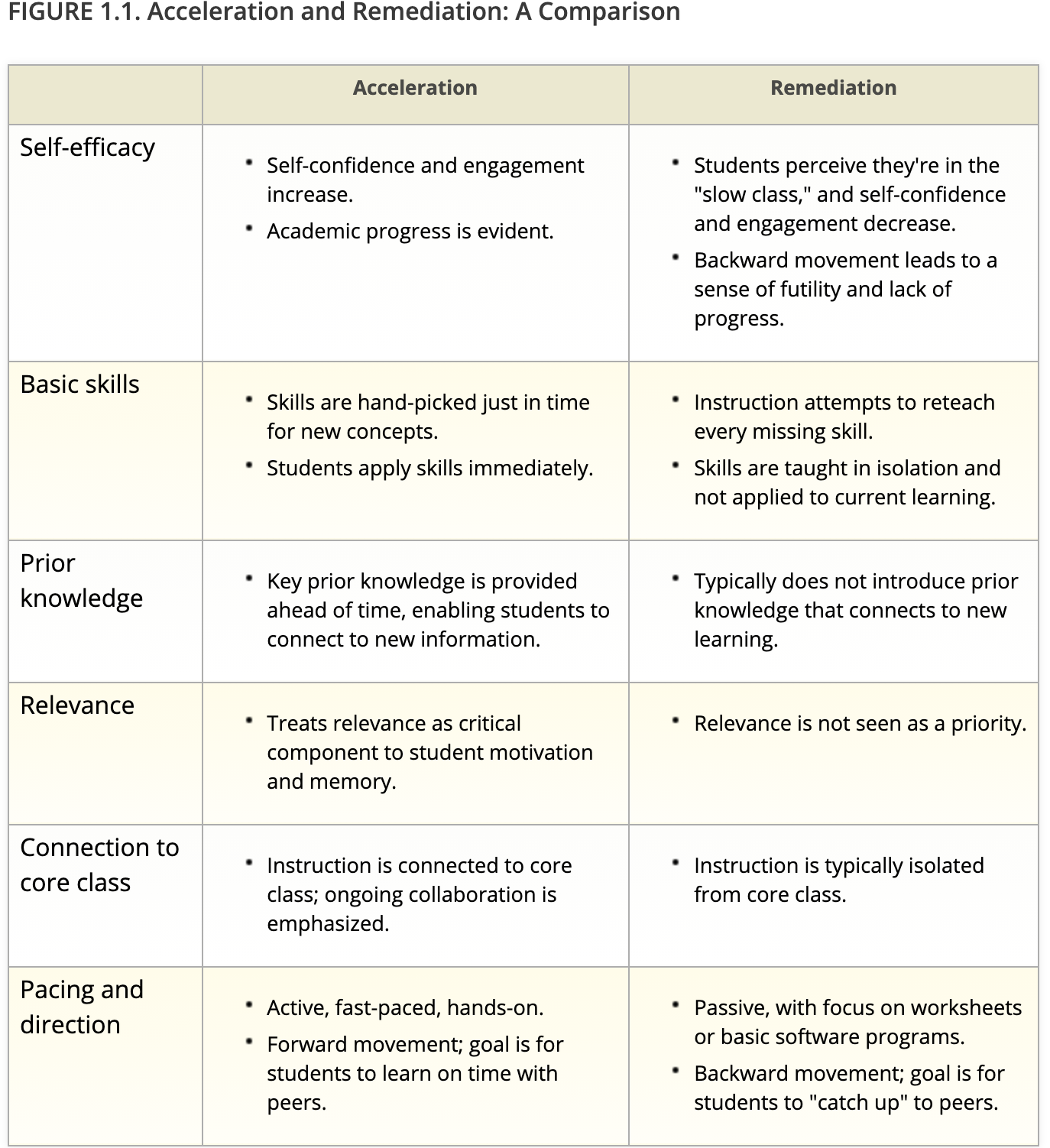

So when should a teacher use acceleration and when should she use remediation? Many experts argue that in today’s world, remediation is rarely successful. Suzy Pepper Rollins’ 2014 book, Learning in the Fast Lane: 8 Ways to Put All Students on the Road to Academic Success, provides a useful table comparing acceleration and remediation.

Next Steps with Acceleration

In the next blog in this series, we’ll take a look at what research says must be in place for effective acceleration to occur.