Ready for more action writing strategies that encourage critical thinking in an AI world? In the first part of this blog entry, you saw three powerful action strategies. Those strategies included collaborative writing workshop, structured debate blogs, and reflective journaling with metacognitive prompts. In this follow-up to part one, you will see two more action writing strategies. These two strategies, just like the first three, are designed to engage student writers and improve their analytical skills.

4. Multi-Draft Writing with Peer and Teacher Feedback

In my fifth grade writing workshop, modeled after Nanci Atwell’s, I had one on one mini-conferences with students. Meeting with them frequently allowed me to gain insight into their writing progress on self-chosen topics of interest to them. During the class period, I delivered mini-lessons addressing specific areas I had noticed in previous conferences. Then, after mini-lessons, I invited students to review their writing to address a particular area of growth. This allowed both the student(s) and I to focus on one component that needed work, rather than a laundry list of issues.

This often resulted in nosy teacher neighbors, red pens in hand, reading student work on the walls with a critical eye. “Can’t your students write?” I would have to explain that their efforts in a particular piece focused on a particular issue, while ignoring others. Over time, their writing improved dramatically as did our relationship, enabling them to take even more ownership of their writing and correcting issues.

This is my understanding of multi-draft writing that incorporates elements such as strategic feedback. Each draft of a piece of writing is improved with a focus on a specific area, eventually until a piece achieves the level desired by the writer. One way to assist students in thinking through their writing involves the use of success criteria or rubrics.

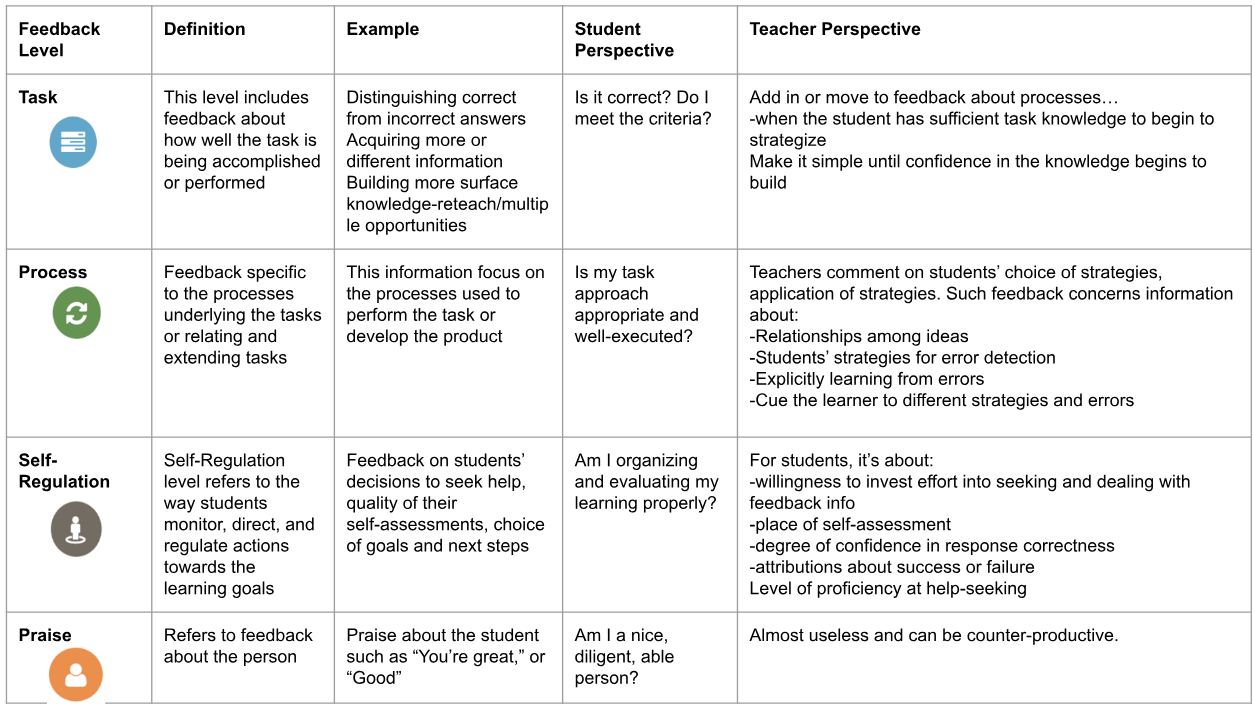

When offering feedback, it’s important to focus on feedback focused on tasks, process, and/or self-regulation. Avoid praise (effect size is 0.14) as feedback. The chart below clarifies the types of feedback to provide (read more):

Adapted from David Perkins (2003) The Ladder of Feedback and John Hattie (2014) The Power of Feedback. You can also: Get Your Own Copy in Google Slides format

Feedback is information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, self/experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding that reduces the discrepancy between what is understood, what is aimed to be understood, and where to move next in their learning.(source)

As you might imagine, Feedback (effect size is 0.51) and “Writing programs” (effect size 0.45) are powerful strategies at play here. In fact, effective feedback answers three questions:

- Where am I going?

- How am I going?

- Where to next? (source)

The approach to use that is quite effective with feedback involves cues and reinforcement (effect size 1.01). That’s whopping big effect size. Reinforcement and cues let students know how to take their next steps in learning, or writing to learn in this case. Let’s look at each in turn below.

Cues that guide the writer towards a desired performance, or help direct attention to important aspects of a task. Think of one on one writing conference or writing circle feedback. This type of feedback often focuses on where and how writing is progressing. Cues can be structured as hints, prompts, or guiding questions.

In regards to reinforcements, encouraging repetition of correct behaviors or offering constructive criticism can be helpful. With multiple conversations about their drafts focused on cues and reinforcement, students engage in iterative revision and analysis. This has the effect of improving critical thinking.

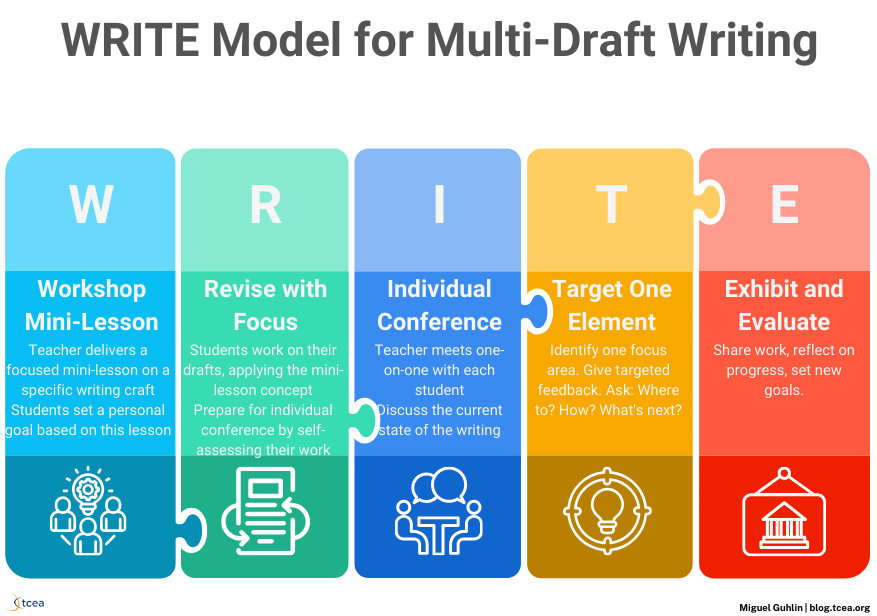

Classroom Application

You can focus on multi-draft essays with the WRITE model for multi-draft writing. It’s pretty easy, as you can see below, and helps keep the focus where it needs to be:

- W – Workshop mini-lesson

- R – Revise with focus

- I – Individual conference

- T – Target one element

- E – Exhibit and evaluate

This model is designed to assist the writing workshop teacher during one on one writing conferences. It’s less useful for students unless they are older and are curious about the process you are following.

5. Cross-Disciplinary Synthesis

A lot of learning takes place at the Surface Learning phase of learning. That is, when new ideas and concepts are being introduced. Most of the writing I most enjoy connects concepts from multiple subjects. It analyzes how those connections are made, and explores the juxtaposition of ideas and information. When the writer makes those connections, the reader in me marvels at the skills and thinking in those hypertext connections.

A component of critical thinking means making visible how authors bridge the distance between diverse concepts. These interdisciplinary connections are the equivalent of poems like Jacob Bronowski’s The Abacus and the Rose. The part of the poem that uncovers for the reader the connection of natural science and emotion for me is this excerpt:

The force that makes the winter grow

Its feathered hexagons of snow,

and drives the bee to match at home

Their calculated honeycomb,

Is abacus and rose combined.

When I first read it in 1984, my mind struggled to see the connections. It was unable to encompass how all the pieces fit together. It’s only now, forty years later, that I see how these connections are made in writing. Making those connections visible is what cross-disciplinary synthesis is about. It is juxtaposing contradictory (on the surface) ideas and seeing what the connection is.

To do this, we have to take what we have learned, have come to understand, and apply it in a way that is new or novel. And that experience shifts our learning from Surface to Deep (where connections are made) to Transfer Learning. It is the last that proves, yes, we see and understand at the deeper level how abacus and rose combine. For this, Transfer Strategies (0.86) and Summarization (0.79) are in effect.

Classroom Applications

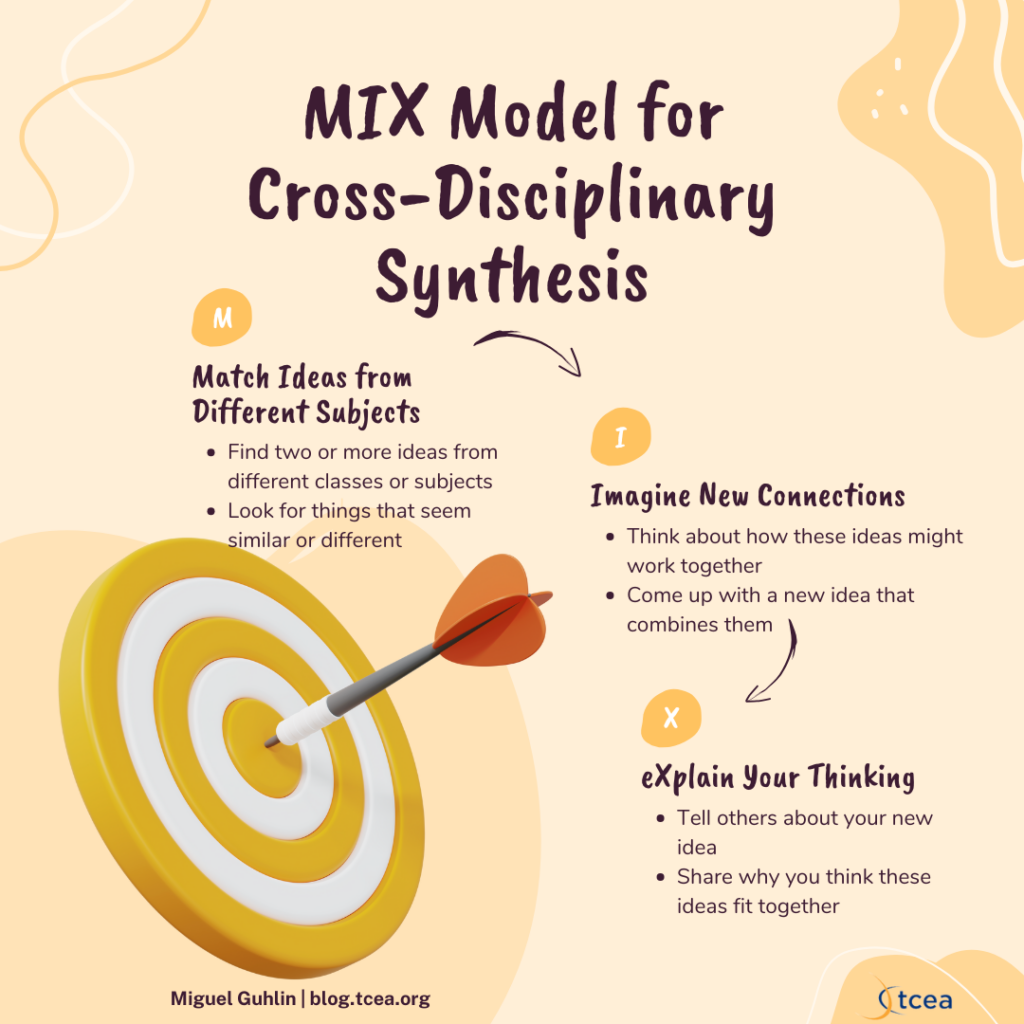

One way to approach this is to use the MIX model (view | get a copy). That is, to encourage openness to seeing ideas from different subjects and how they connect to one another. The MIX model includes:

- M – Match ideas from different subjects or disciplines

- I – Imagine new connections

- X – eXplain your thinking

Here’s an example of what that might look like from the perspective of a fifth grader:

Here’s the updated markdown table with a merged row at the end containing a sample narrative in a fifth-grader’s voice:

| M | I | X |

|---|---|---|

| Match ideas from different subjects | Imagine new connections | eXplain your thinking |

| In science, we learn about force and motion. At home, we play kickball. | Kickball shows force and motion in action. Kicking uses force. The ball moves. We run and stop. We catch the ball. | Kickball is like a force and motion game! |

A MIX Example: Force and Motion

“Hey guys, watch this!” I yelled as I ran up to kick the bright red ball. My foot connected with a satisfying thud, and the ball soared through the air. As it arced across the sky, I couldn’t help but think about our science lesson.

“Whoa, nice kick!” my friend Jess shouted. “How’d you do that?”

I grinned, feeling proud. “It’s all about force and motion,” I explained. “Remember what Ms. Rodriguez taught us? The harder I kick, the more force I use, and the farther the ball goes.”Jess’s eyes lit up. “Oh yeah! So when I catch it, I’m stopping its motion, right?”

“Exactly!” I nodded enthusiastically. “And when we run bases, we’re changing our own motion. It’s like we’re doing a science experiment while we play!”

As we continued our game, I saw force and motion everywhere. The bounce of the ball, the sprint to first base, the arc of a throw – it was all science in action. Who knew our neighborhood kickball game could teach us so much?

Turning the Page

When I turned twenty something, I switched from handwriting notes to typing. I had been writing with a word processor since age thirteen, and it made sense to type, not write, my notes. Then, when I read the research, newly presented a few years ago, I switched back to handwritten notes. What a difference! This quote founds its way to my inbox:

“When we measure the brain activity of people who write by hand, we see that they form more connections in the brain than when they write using a computer,” says brain researcher .

Audrey van der Meer, a professor of neuropsychology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) as cited in Futurity.

More connections is good, right? I can’t imagine writing this blog series by hand, though. Not with all the links and edits I’ve made. Instead, I write my notes by hand, then put them into a word processor as an article. When I see technology, now AI, short-circuiting the brain activity made possible by handwriting, I do worry a little. But we need to do the hard work. We need to model writing by hand, note-taking, concept mapping, and more with students in the classroom. In my classrooms in Texas K-12 public schools, I did that. But the writing workshop remains a contentious time sink for some educators, administrators, and legislators. The arrival of AI on the scene underscores the importance of NOT ignoring the research any more. Even if it means saying, “AI may not be right for our children to use until after they have activated their brains more.”

Get a Copy of These Action Writing Strategies

Want a copy of the action writing strategies featured in this blog entry? Get a copy via Canva, and/or view full-size. All images, including the feature image, were created by the author and are freely shared to spur learning and inspire your creativity, AI-assisted or otherwise. What’s more, you are free to use these. To generate the ideas for these models, I wrote each section, then fed that into Perplexity.ai. I asked it to give me a model appropriate for grades 3-12 that would match my writing. Then, after reviewing it, I fine-tuned the model in Canva for the posters.

The Inspiration Behind These Action Writing Strategies

This blog entry on action writing strategies was inspired by two articles I read about the despair teachers are experiencing surrounding AI. The two articles are ChatGPT Can Make English Teachers Feel Doomed: Here’s How I’m Adapting by David Nurenberg (Education Week, 10/16/2024) and I Quit Teaching Because of ChatGPT by Victoria Livingstone (Time, 09/30/2024).

How are you coping with AI? Let us know in the comments below!