Simulations, games, role playing activities, and more have been a part of education from the beginning. Sometime games can help students focus on a task or remember a concept through repetition. Sometimes, they can help students work through several stages of understanding, from comprehension to synthesizing new ideas. Games can also teach social-emotional learning, and in the case of in-person games, and even spatial learning and reasoning.

One game that does all of this is the World Game, a physically (and mentally) huge simulation meant to get people to think critically about global issues and even find practical, measurable ways to achieve the audacious goal of world peace. It was an idea ahead of its time, reliant on massive troves of data that only today are accessible to most of the public. With today’s ability to find and use big data from around the world, it’s a good time to revisit the simulation game designed to save the world.

A Man Named Buckminster

Richard Buckminster Fuller (Buckminster or “Bucky” to his friends) is widely regarded as an American architect and thinker, and perhaps best known as the popularizer of the geodesic dome and the expression “Spaceship Earth.” Indeed, his eventual idea for an educational game was based on his belief in the Earth as one system of many systems, one machine with many moving parts.

Efficiency is perhaps the watchword for Fuller’s famous “practical philosophy.” This meant not only knowing verifiably what was available, but also how it could be used most simply and without waste. To this end, much of Fuller’s philosophy was democratic and far-reaching, even Utopian. He believed information must not only be collected, but shared widely. After all, many heads make quick (and efficient) work.

Fuller and Dymaxion

In the early 20th century, Fuller began to develop an idea that would come to define his career and legacy, an idea called dymaxion, which was a portmanteau of dynamic, maximum, and tension. The philosophy has been succinctly described as “maximum gain of advantage from minimal energy input,” or put another way, “more with less.”

This notion went on to shape the course of Fuller’s career and his contributions to design and architecture, first in 1930 with the Dymaxion house, then in 1934 with the Dymaxion car. This concept would stay with Fuller, and eventually influence the creation of the World Game, a wildly ambitious and though-provoking idea for an educational simulation.

A Man Named Shoji

While teaching at Cornell University in the early 1950s, Fuller took on a bright new student, Shoji Sadao.

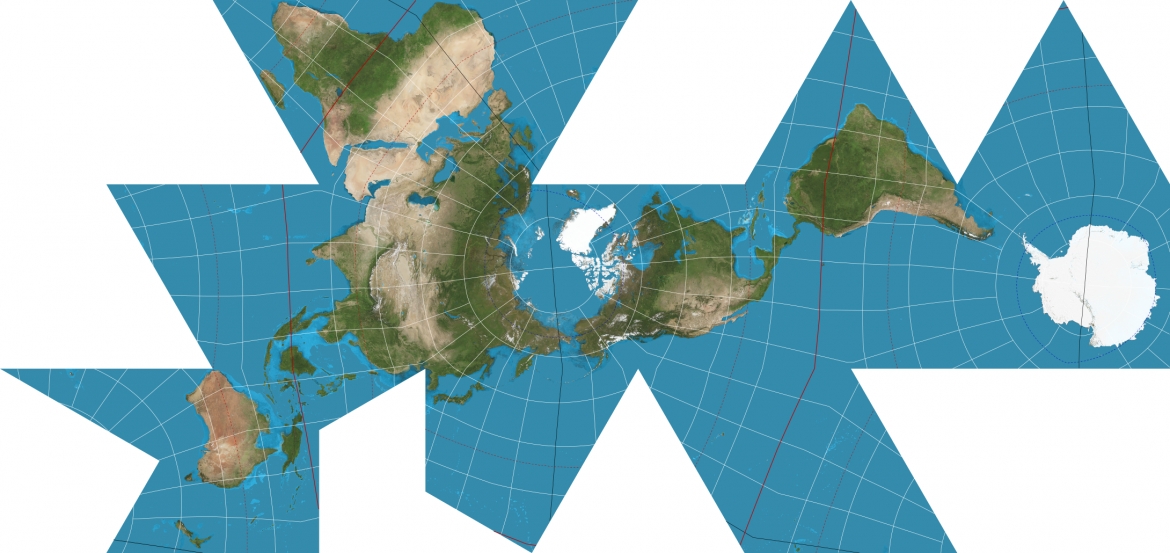

The Japanese American future architect had been interned with his family at the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona during World War II, but was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1945, where he spent five years as a cartographer. By 1954, Sadao helped Fuller create the next piece of his dymaxion project, the “Dymaxion map,” or “Airocean World Map.”

Fuller and Shoji’s map was meant to display the entire planet at once with minimum warping of relative sizes. To do this, they projected a world map onto an icosahedron, or 20-sided figure. This accounts for the map’s strange breaks when projected on a flat surface. Notably and intentionally, however, the Dymaxion projection displays the Earth’s landmass as one contiguous piece — connected, rather than separate.

Sadao went on to work with famed Japanese American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. When he died in 2019, the New York Times called Sadao “the “quiet hand behind two visionaries,” Fuller and Noguchi.

The Game

According to the Buckminster Fuller Institute, the game is meant to, in the words of Fuller himself, “make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone.” The Dymaxion map was the perfect choice for a grand, in-person learning game focused on worldwide concerns.

Fuller conceived of a game that would help students think about, understand, and ultimately become responsible stewards of big, global systems, from air, water, and soil, to the movements of people, resources, and more. The World Game posits that informed students can grow up to be smart users of world economies, resource flows, and ecologies by understanding the planet as one interconnected system. In Fuller’s eyes, these engaged learners could help create a planet where resources and human needs are, in a sense, held in dynamic maximum tension in order to support itself; dymaxion.

Premise

Originally, Fuller’s idea was the stuff of science fiction — and probably closer in practice to a war game simulation than an educational game. But throughout Fuller’s life and after, it’s been a powerful thought experiment. At the time the game was being developed in the 1960s and ’70s, however, world governments were practically the only entities powerful enough to collect all the information needed, much less create Fuller’s idea of a computerized map the size of a football field that could reflect decisions in real time. As a professor at Southern Illinois University, he worked to build the technological infrastructure to execute the game.

It is played with the information contained in the six volumes entitled, “Inventory of World Resources, Human Trends and Needs,” compiled and published by my office at Southern Illinois University. …

Our world game will be played electronically by remote controls on a giant model of our earth globe opened out into its flat projection which will be the size of a football field. (See my world map.‘) World leaders will be invited to play the game and to introduce any new data they deem to be missing and the computers memory banks will retain all the data ever fed into it as well as remembering all the plays that have been previously made and their respective outcomes.

R. Buckminster Fuller, testimony to U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Intergovernmental Relations, March 4, 1969

The game’s expansiveness meant that it “remained largely speculative and pedagogical throughout Fuller’s life – appearing primarily through copious research reports, resource studies and ephemeral workshops – Fuller claimed that he had been “playing it ‘longhand’ without the assistance of computers since 1927.”

Even in its earliest stages, however, Fuller and likeminded thinkers saw the potential of the World Game, or a simulacrum of it, as an educational tool. The game itself is a kind of stealth planning, or resource management, simulation. Armed with the Dymaxion world map and reams of data on literally everything, something that only today is becoming close to possible, players would watch the outcomes of their choices on the Earth itself.

A core tenet of the game is the impetus for students to understand global systems and connections. The game itself requires massive amounts of data. The premise, put simply, was to compile all vital data about planet Earth, then help players find ways to move resources where they’re needed without overloading the system. An astounding premise, for sure, but one that could be broken down into several sub-games, or scenarios. Today’s technology, of course, makes it much easier to use Fuller’s premise in education.

“The question of global modeling is something you find elsewhere. But other people don’t design structures for it and produce pedagogical models like the World Game.”

Mark Wasiuta, “Check Out Buckminster Fuller’s Simulation to Save the Planet.” Curbed.com

It was a characteristically ambitious idea — impossibly ambitious to some — but especially aspirational when it was being developed in the 1960s, before TV news, big data, or the internet. As the Fuller Institute explains:

Fuller wanted a tool that would be accessible to everyone, whose findings would be widely disseminated to the masses through a free press, and which would, through this ground-swell of public vetting and acceptance of solutions to society’s problems, ultimately force the political process to move in the direction that the values, imagination and problem solving skills of those playing the democratically open world game dictated. It was a view of the political process that some might think naive, if they only saw the world for what it was when Fuller was proposing his idea (the 1960s) – minus personal computers and the Internet.

About Fuller, “World Game.” Buckminster Fuller Institute

The World Game is, after all, mostly a premise, and as early as 1969, educators were adapting it into teaching games with focused topics. Modern ed tech might give us new ways to use some of the game’s proposed elements, like scientific and population data, and its principles of participatory learning as a way to illuminate ways to actually improve the world.

Gameplay

Fuller envisioned a series of workshops using his concept of “design science,” a process of developing ideas not unlike the Engineering Design Process, allowing players to work their way to a solution to those smaller scenarios, like how to distribute power worldwide.

Through several iterations and using flexible techniques, players use data to develop or test (model) a proposed solution to a global problem. In a 1971 World Game packet, Fuller gives the example of students considering automobile emissions.

At present, there are at least two approaches to formulating and documenting World Game strategies. One is mentioned above — inventory, trend, then inductively come up with a strategy to anticipatorily meet the needs you see. For example — another trend, that of Carbon monoxide (CO) production, when compared with the automobile trend would lead one to the conclusion that somewhere around the year 2000, the CO from the increased number of automobiles would do irreparable harm to the planet. One could anticipatorily design a CO-less engine to meet that emergency, or better yet, a total pollutionless transport industry.

Another approach is a deductive one-that is, start off with the strategy, and then document your intuition of it through the inventories and trends that are relevant to it.

The World Game: Integrative Resource Utilization Planning Tool (1971). R. Buckminster Fuller.

Learning Outcomes

The Power of Simulation

Looking to use a World Game-inspired simulation in your teaching? Today, there are remote learning and in-person ways to using gaming and simulations. But how well do they work?

The Visible Learning MetaX project, based on the research by John Hattie, classifies gaming and simulations as “likely to have positive impact” on learning. Meanwhile, Hattie gives tactile simulations, in which “students who struggle with achievement in school are provided with tactile stimulation and environment manipulation aimed to increase focus and time-on-task and attention,” has an estimated effect size of 0.58, or as having a “potential to accelerate” learning.

Fuller’s game was meant to be played in person and on a giant-sized mat, no less. Today, a number of similar simulations are using simulation activities both online and in person, some inspired directly the World Game.

Remembering the World Game in the Digital Age

Since 1969, the World Game has been adapted by educators in many ways, as technology has caught up with Fuller’s vision of a data-driven, cooperative scientific and economic simulation. By the 1980s, more pedagogical ideas and new technologies allowed the game to be realized in ever more substantial ways.

In 1980, the World Game Institute and the World Resources Inventory published the World Energy Data Sheet, which compiled a nation by nation summary of energy production, resources, and consumption. Further, they developed the world’s largest and most accurate map of the world, one of the most detailed and substantive databases of global statistics available anywhere, and educational resources designed to teach interdependence, collaboration, respect for diversity, and individual participation in a global society.

“World Game (1961)” Games For Cities

In 2001, the educational company o.s. Earth bought the principal assets held by the World Game Institute. Soon after, they began leading “Global Simulation” workshops, which Games for Cities, a group that promotes public affairs simulations, or “city gaming,” calls o.s. Earth’s workshops “a direct descendant of Buckminster Fuller’s famous World Game.”

Even more attention came to the game in 2015, when the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University hosted an exhibition on the topic entitled “Information Fall-Out: Buckminster Fuller’s World Game.”

In 2019, o.s. Earth’s assets, including those it secured from the original World Game Institutes, were acquired by the non-profit Schumacher Center for a New Economics, now home of the World Game Workshop.

For those looking to carry out similar educational games, a number of them, each with different focuses and features, exist, from high-level management simulations to role-playing life simulators to even history simulators. Check out ESC 13’s list of simulation and game activities. Have you own idea for educational simulations and games? Let us know in the comments.