Dear TCEA Responds:

I wanted to do a demo today to clarify misconceptions about why the Earth has seasons. What I ended up with was kids arguing with me in many classes that the Earth is flat and what I’m teaching is wrong. I couldn’t even finish my lesson because they would not stop interrupting me.

Thanks in advance for your ideas,

Jim

Dear Jim:

As a high school senior, the crowning assignment of my English class involved writing a paper. The research paper assignment, which you may be familiar with, had to address an important topic. No topic is more important than the story of human evolution. So that was the topic I wrote about. At my Catholic High School in Texas, it wasn’t controversial at all to share the fact, but the theory was another matter. There is no such thing as a casual reading of evolution when considered in the context of society. Though the facts seemed incontrovertible, the theory of how they got to be facts caused endless debate.

Evolution remains a controversial topic and an untruth for many. Even among professionals, it is a belief rather than a fact.

The Power of Culture

One of my favorite episodes of “Friends” pits Ross against Phoebe over evolution. Like some in the listening audience, I marvel at Ross’ approach. He bungles a clear elucidation of the facts of evolution, the scientific theory, and more.

Phoebe takes a gleeful approach to demolishing Ross’ argument. For many of us who recognize evolution as a theory that explains incontrovertible facts, the argument isn’t worth the effort. What does Ross gain in this argument with Phoebe? It doesn’t matter because it’s comedy.

In your classroom, Jim, you can’t leave well enough alone. This isn’t Sunday school where beliefs are taught, but rather, the scientific method and the observation of phenomena. At Ecology for the Masses, freshwater ecologist Sam Perrin writes:

There are two reasons why we shouldn’t take the “there’s no point even trying with these people” approach. There is a chance they will understand the basis of an important scientific concept. And even if that doesn’t work, talking about evolution is a great chance to tell scientific stories. Talk about how whales or horses started, how human pubic lice evolved, why ducks and geese are…evil. They might go away with a few fun stories to spread around. (edited for readability)

Reading Johnjoe McFadden’s book, “Life is Simple: How Occam’s Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe,” highlights a simple fact. Science denial has been around for a long time. Let’s explore five reasons why dealing with disinformation is hard.

“You have to disentangle the details. You have to hold up every one independently, and ask, “How do we know *this* detail?” Where are all these details coming from? Where did *that specific* detail come from?”

― Eliezer Yudkowsky as cited in “Life is Simple: How Occam’s Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe”

Dealing with Disinformation

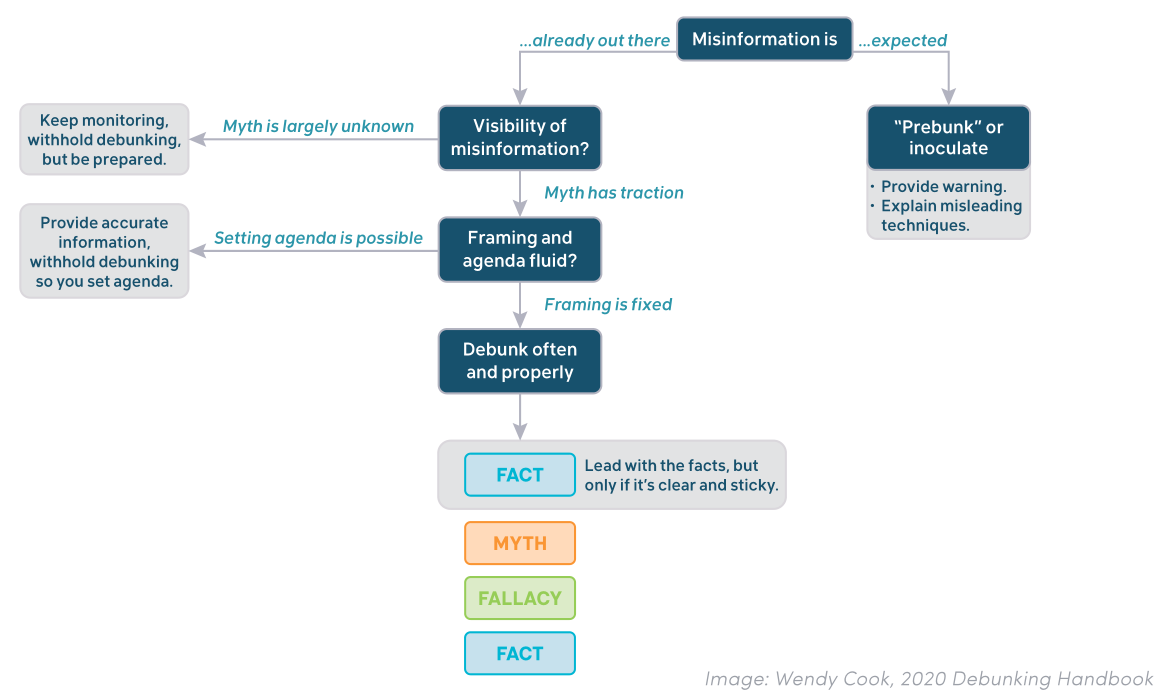

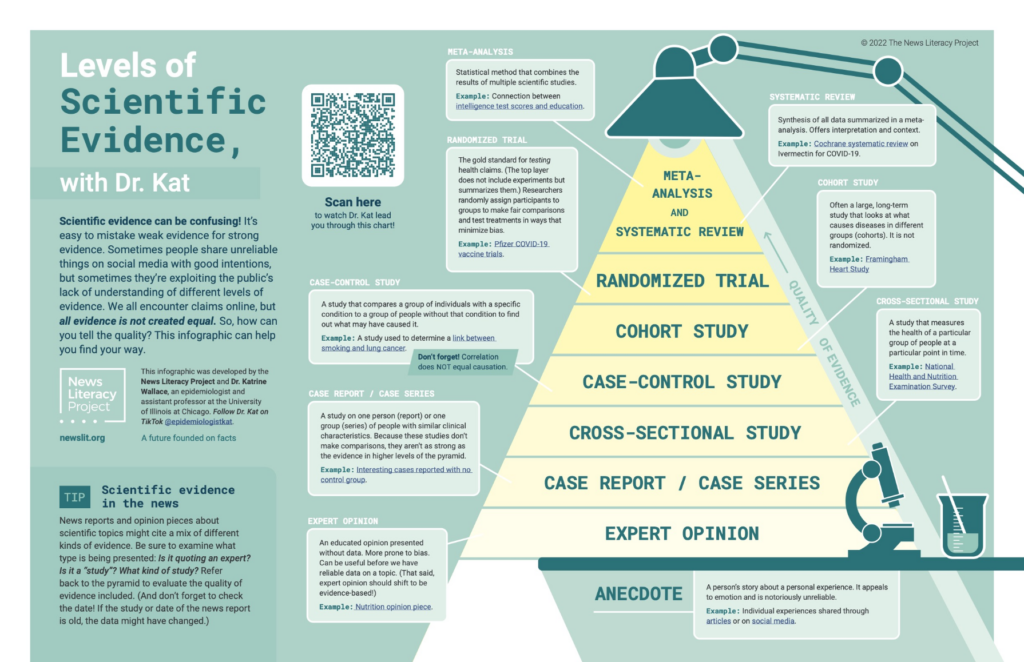

Science denial often presents as a problem of disinformation. You can see it in this chart by Wendy Cook in the 2020 Debunking Handbook:

In Wendy’s approach, a simple formula is suggested. The “truth sandwich” formula has one presenting each component below:

- Fact. Lead with clear facts that are easy to remember (“sticky”).

- Myth. Share what was false.

- Fallacy. Explain what was false is wrong, and how it differs from facts.

- Fact. Share the facts again in a clear, easy-to-remember approach. (source: Journalist Field Guide via CAAD)

As Sam Perrin points out, the fun stories help convey the facts in a memorable way. Why is science denial, accepting and promoting disinformation, so easy?

Five Reasons for Science Denial

Why is it so hard to handle societal-based claims that are contrarian or deny science? Here are five reasons why from Beth Daley:

- Social identity. What we believe and what we share flows from whom we identify with. If those we identify with disagree with an aspect of science, we do as well.

- Mental shortcuts. Thinking is hard. It’s easier to assume something is true because it’s what we want, and we don’t have to think about it, even if it is false.

- Beliefs about what you know. We all have beliefs that are certain. It’s that certainty that is the problem. Scientists are more tentative about what is held to be true since new evidence can change that truth.

- Unconscious bias. If you have a bias, failing to identify it can skew your reasoning when examing evidence. That means your bias can lead you to the conclusion you want rather than the conclusion the facts point to.

How to Face Science Denial

What does one do in the face of science denial? How can you transform your didactic class into one focused on critical thinking? Some ways to deal with these reasons include:

- Listen and find common ground.

- Ask yourself, “How do I know this is true?” and check into facts.

- Avoid acceptance of information you believe to be true. Adopt a scientific attitude that relies on evidence-based science.

- Inventory your biases and assess information sources in light of those biases.

Give students a way of considering how their thinking and biases interact.

System 1 thinking is a near-instantaneous process. It is automatic, intuitive, and with little effort. It’s driven by instinct and our experiences. System 2 thinking is slower and requires more effort. It is conscious and logical.

Even when we think that we are being rational in our decisions, our System 1 beliefs and biases drive many of our choices. Understanding the interplay of these two systems in our daily lives can help us become more aware of the bias in our decisions – and how we can avoid it. (source)

A complementary approach involves modeling critical thinking. You can have students inventory their biases, beliefs, and taboos. Then ask how those may limit their openness to evidence-based facts.

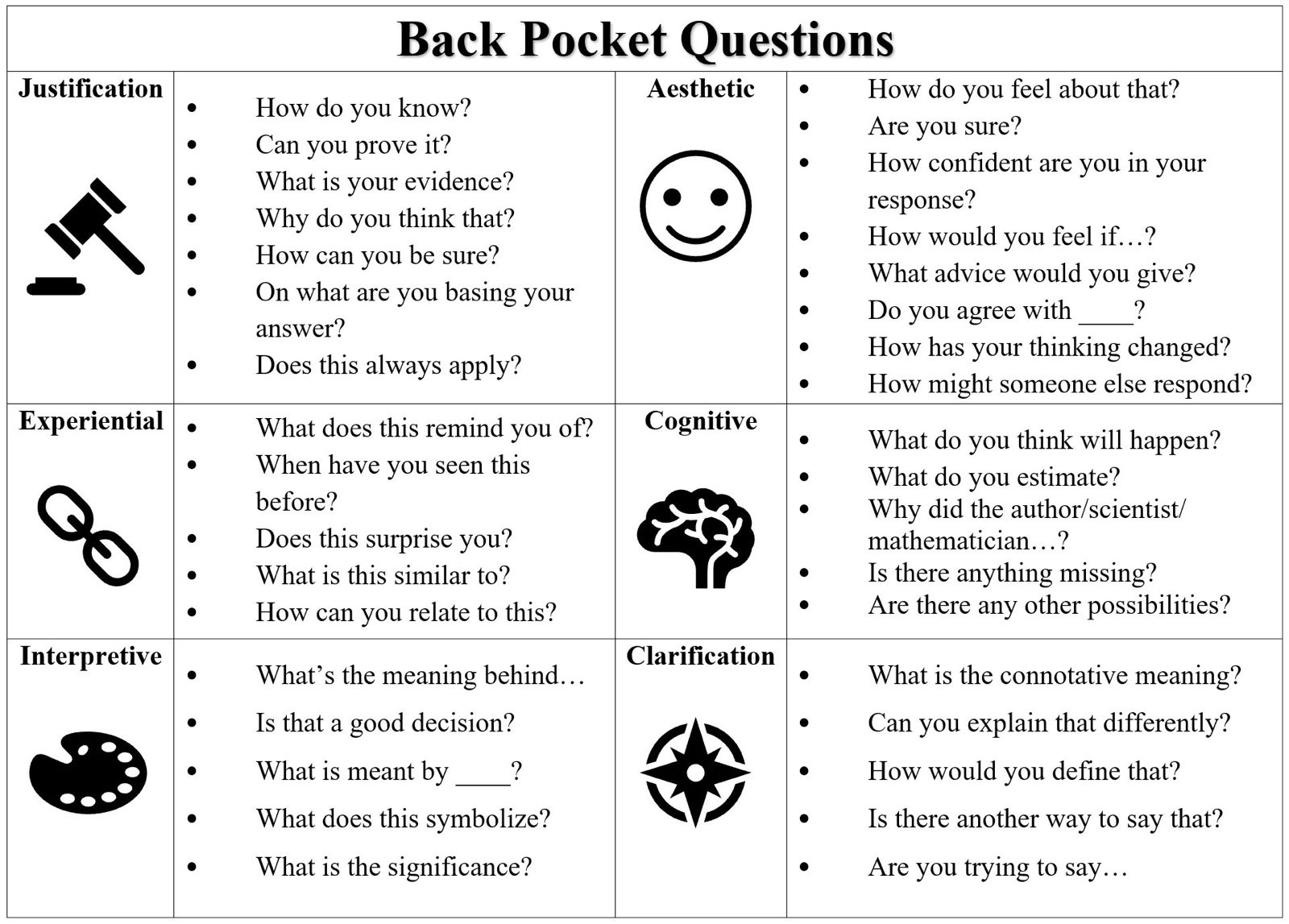

Back Pocket Questions

Consider taking an approach that spurs conversation rather than shuts it down. One way is to use Back Pocket Questions, discussed in the video above. One document worth encouraging students to keep in mind is a back pocket questions chart.

Here’s one version shared with me (source unknown):

Most importantly, build a relationship with students. Often, students’ lack of critical thinking reflects a low level of trust in the classroom in general.

Many people don’t trust the society around them, most notably the representatives of that society. That trust often falls even further when it comes to elite representatives of that society, which include government officials, members of academia, and scientists like me.

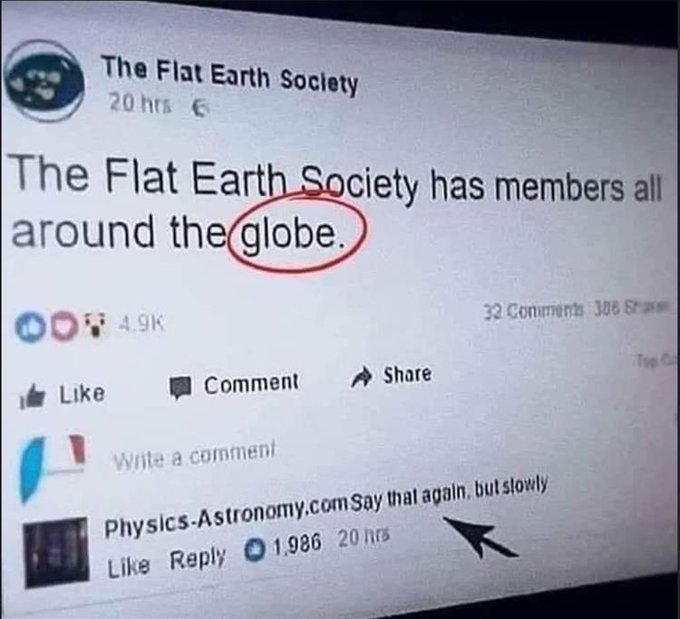

By claiming that Earth is flat, people are really expressing a deep distrust of scientists and science itself.

So if you find yourself talking to a flat-Earther, skip the evidence and arguments and ask yourself how you can build trust. (source)

More Reading

- Allan, Andy. (2016). Five Tips for Cultivating Creativity and Curiosity.

- McFadden, Johnjoe. (2021). Life is Simple: How Occam’s Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe.

- McIntyre, Lee (2020). The Scientific Attitude: Defending Science from Denial, Fraud, and Pseudoscience.

Learn more about open-ended and back-pocket questions.

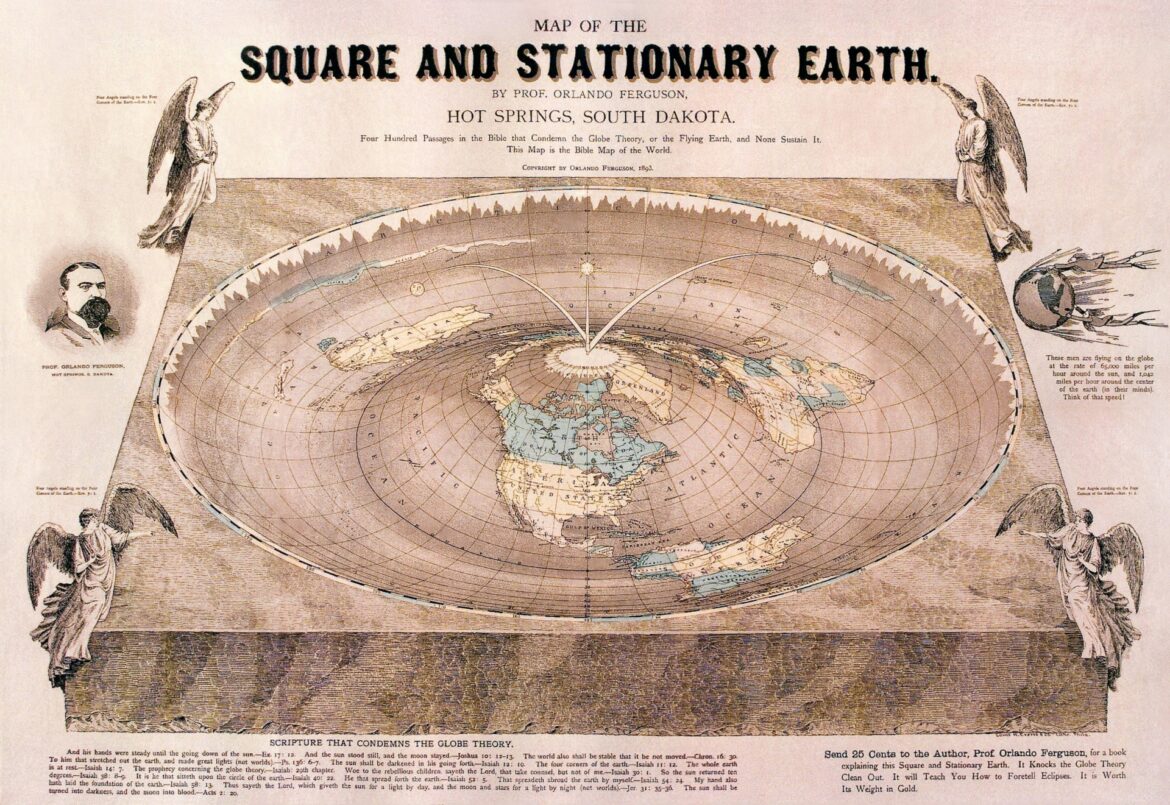

Feature Image Source

Flat Earth Map (Public Domain)