In recent years, writing across content areas has become a highly discussed literacy problem of practice. As assessments across the country—including the redesigned STAAR exam—incorporate cross-curricular passages and varied writing tasks, many districts are asking, “How do we build a culture of literacy that spans content areas?”

While we can all agree that building student literacy is incredibly important, different educators are likely to come up with different definitions of what “literacy” means. For the sake of the discussion below, I want to offer a definition that many of our teams at NoRedInk utilize: Literacy is the ability to read, interpret, write, and discuss ideas across varied contents and contexts.

This expansive understanding of literacy makes space for literacy interventions not just in ELAR classes, but in all classes. By embracing this kind of “disciplinary literacy,” districts can equip students with the skills and knowledge they need to succeed in school, higher education, the military, and the workplace.

What Does Disciplinary Literacy Look Like?

Promoting disciplinary literacy involves helping students step into the shoes of experts in a given field, asking them to engage in social and cognitive practices consistent with those content experts. Doing so gives purpose to classroom reading and writing tasks, which in turn gives students greater access to texts and artifacts.

In practice, this might look like preparing students to read a cartoon like an historian, note features of a painting like an artist, read a graph like a scientist, write a song like a musician, or analyze a play like a football coach.

Naturally, non-ELAR teachers are uniquely equipped to help students develop these varied literacies. What they may be less equipped to do is teach spelling or conventions or proper essay structure—and that’s okay! Just because a district incorporates writing across its curriculum doesn’t mean that every teacher must moonlight as an ELAR teacher. Rather, an effective disciplinary literacy initiative draws on the strengths of each teacher to support the development of historically, artistically, scientifically, musically, and athletically literate students.

Building a Culture of Literacy

As the research of Paige Whitlock, EdD, illustrates, coming to a shared understanding of what disciplinary literacy does and doesn’t mean is just the first step in building a culture of disciplinary literacy in a district. Leaders must also invest in clear planning and communication to get teachers on board with their initiatives.

First, leaders should foreground the “why” behind the move toward writing across the curriculum (or whatever disciplinary literacy initiative they’re rolling out). Every district faces a unique set of circumstances, but as a leader, you should be sure to make it clear why it’s important to you, your district, and your community to increase literacy across content areas.

It’s equally important to draw clear connections between new disciplinary literacy initiatives and ongoing initiatives in various content areas. Literacy cannot seem like yet another thing competing for space on non-ELAR teachers’ plates. Better thinkers and better writers make better historians, artists, scientists, and so forth, which means disciplinary literacy is not “for someone else,” but a powerful tool for teachers in every subject. Get non-ELAR teachers involved in planning literacy initiatives so that these initiatives fold into what these teachers are already doing.

Finally, on a similar note, lean into distributed leadership. ELAR leaders may be in the best position to spearhead a literacy initiative, but they shouldn’t hesitate to leverage the expertise of central office specialists, school administrators, and, as mentioned above, strong teachers (both ELAR and non-ELAR). Create a literacy team dedicated to mapping out essential steps in your literacy initiatives and exploring opportunities for the district to embrace a more expansive definition of literacy.

A South Texas Success Story: Creating a Culture of Disciplinary Literacy

After adopting NoRedInk Premium across all their secondary schools in the ‘21–‘22 school year, Weslaco ISD, a suburban district in the Rio Grande Valley serving almost 20,000 students, noticed that writing was happening almost exclusively in ELAR classrooms. They decided to craft a plan for increasing writing across content areas starting in the spring of 2022.

Weslaco assembled an implementation team made up of both Social Studies and ELAR teachers that zeroed in on prioritizing non-fiction, analytical writing skills and providing feedback on students’ writing through their respective content area literacy lenses. The implementation team then introduced the Weslaco curriculum team to their new approach, and the latter worked to incorporate Social Studies-related prompts into their ELAR scope and sequence and align Social Studies writing tasks with the skills students were learning in their ELAR classes.

In the fall of 2022, Weslaco trained all Social Studies and ELAR teachers on the new approach and orchestrated norming conversations so teachers understood which content areas owned which components of writing. Before the start of the ‘23–‘24 school year, Weslaco repeated the same process with Science teachers across the district.

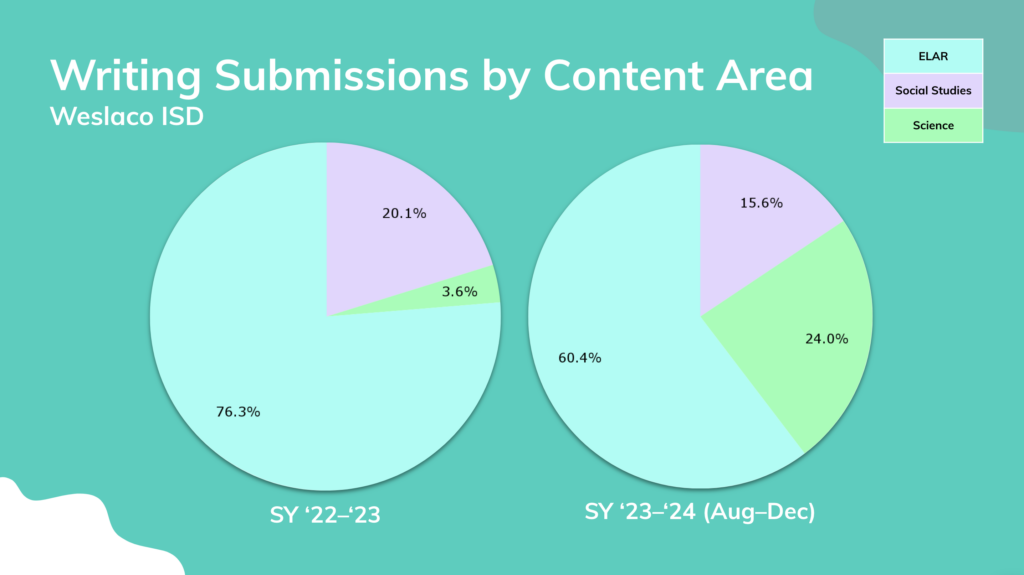

As a result of these efforts, the amount of writing students completed more than doubled from the ‘21–‘22 school year to the ‘22–‘23 school year. Critically, much of this growth was the result of a significant uptick in the amount of writing happening in non-ELAR classrooms.

Prior to ‘22–‘23, the overwhelming majority of writing in the district was occurring in ELAR classrooms. In ‘22–‘23, ~76% of student writing submissions came from ELAR classrooms, whereas ~20% came from Social Studies classrooms and ~4% came from Science classrooms. In the first half of ‘23–‘24, ~60% of student writing submissions came from ELAR classrooms, whereas ~16% came from Social Studies classrooms and ~24% came from Science classrooms.

How to Get Started

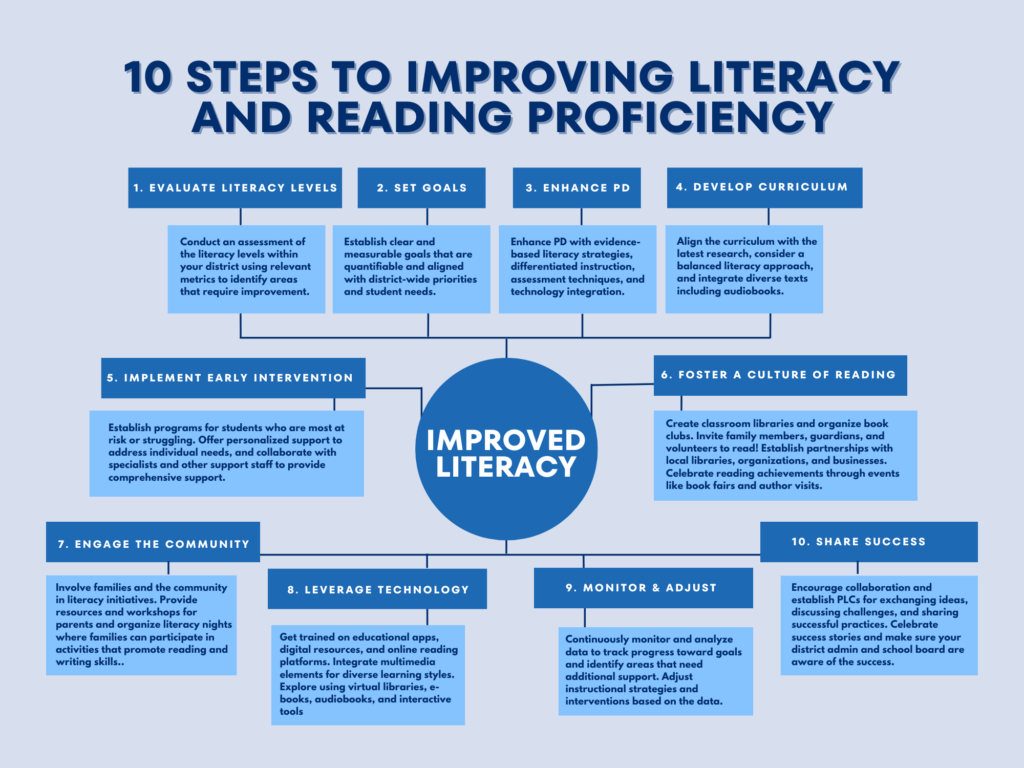

As the initiative in Weslaco ISD illustrates, building a strong districtwide culture of disciplinary literacy is a multistep process that can take time to execute effectively. That said, there’s nothing wrong with starting small.

To get the ball rolling, consider organizing a book study, incorporating more reading and writing tasks into PLCs, or putting together a cross-curricular team tasked with defining “literacy” within each discipline. Especially at the start, baby steps are much preferable to no steps at all, because ultimately, regardless of your district’s specific goals, developing student literacy across multiple content areas is a surefire way to set your students up for success.